Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Kate Fullagar, Associate Professor in Modern History, Macquarie University

Captain James Cook arrived in the Pacific 250 years ago, triggering British colonisation of the region. We’re asking researchers to reflect on what happened and how it shapes us today. You can see other stories in the series here and an interactive here.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people.

Several recent exhibitions on James Cook have sought to include discussions of the Indigenous people who journeyed with him on his Pacific voyages.

In exhibitions marking the 250th anniversary of the Endeavour’s departure from Britain in 2018, for example, both the British Library and the National Library of Australia focused in part on the priest Tupaia, who travelled with Cook from Tahiti to Batavia (present-day Jakarta) in 1769.

These exhibitions emphasised Tupaia’s navigational prowess, but didn’t provide extensive detail on the role he played in the British enterprises.Likewise, little to no attention has been paid to the islander who journeyed with Cook the longest, Mai, who joined the captain’s second and third voyages.

Shining a light on the islanders who travelled with Cook is necessary to put his achievements in proper context. Cook was more reliant on their assistance for his empire-expanding project than is often acknowledged. And these islanders had more agency during the so-called Age of Discovery than is typically believed.

The stories of Tupaia and Mai highlight the central role Indigenous people played during this period, which for too long has been described as one of only European exploration. And they also question the way Cook has been portrayed throughout history – as a lone genius, connecting the world more closely through his unique abilities.

It turns out many different people contributed to globalisation in the 18th century.

Tupaia’s motivations for joining the Endeavour

Mai, or Omai as he was mostly known by the British, shared many characteristics with Tupaia. Both were motivated to journey with Cook because of intense dramas playing out on their home island of Ra‘iatea in what is now French Polynesia. And both became useful to the British voyagers by brokering introductions with other islanders in the Pacific.

But in other ways, the two men differed. They were from separate social ranks and they experienced very different fates.

Tupaia was of the exalted ari’i rank, a leading priest of the ‘Oro sect that ruled most of the Tahitian archipelago during this era.

Because of his high status, he was directly involved in a tumultuous war between Ra‘iatea and neighboring Bora Bora in the 1760s, which eventually ended in defeat for the Ra‘iateans. After the war, he became a refugee in Tahiti, where he came into contact with the Endeavour and befriended the naturalist, Joseph Banks.

For Tupaia, the motivation to join the Endeavour voyage was complex and political. He saw in the British tallships an opportunity to gain arms, knowledge and possibly even men for a restorative offensive against the Bora Borans at Ra‘iatea.

Some descendants today also suggest he joined the crew as a way of continuing a long-established practice of voyaging – returning to islands he had previously visited in his own waka (canoe) and by his own navigational techniques.

And Banks saw in Tupaia’s adventurousness a chance to fulfill a dream to study man in a so-called “state of nature” back home in Britain.

Tupaia’s assistance during the voyage

Tupaia joined the Endeavour in July 1769. Cook, until now skeptical of including islanders in his crew, acquiesced partly because he saw it appeased Banks and partly because he judged Tupaia

a Shrewd, Sensible, and Ingenious Man.

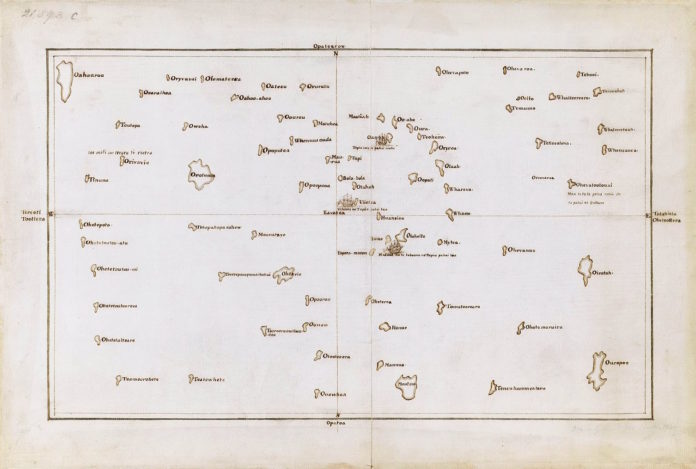

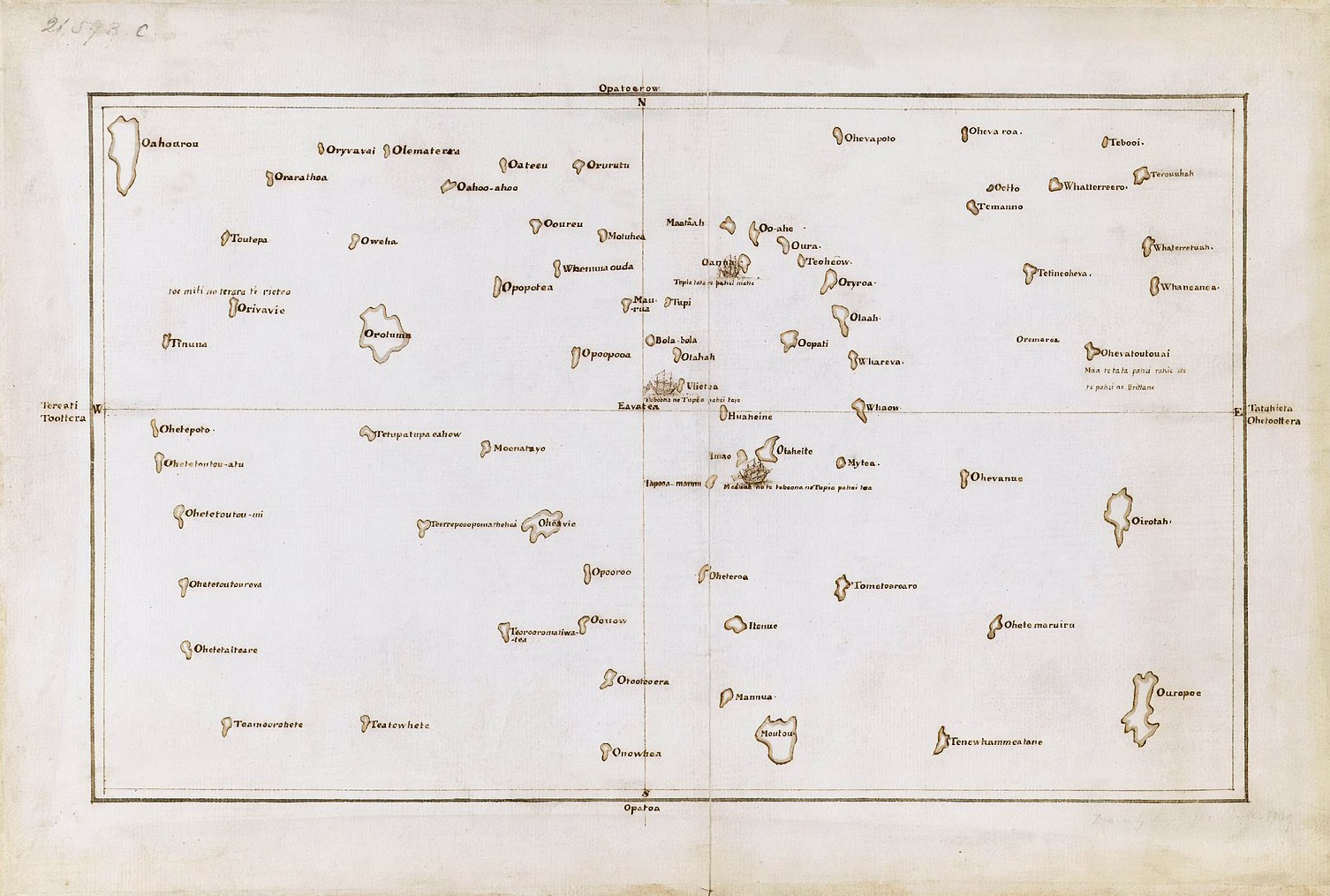

The captain learned a great deal from Tupaia. Not only did Cook listen to and attempt to document all of Tupaia’s recitations on the scores of islands around Tahiti, he also gained rare insight into Pacific voyaging.

Most of all, he had Tupaia’s help when he met wary islanders in other archipelagos. With Tupaia mediating, these encounters went smoothly.

Tupaia was ill through much of the Endeavour’s stay at Botany Bay. Unfortunately, his health only worsened and he died during the ship’s layover in Batavia, thwarting Banks’ long-term aim of bringing him to Britain.

Perhaps, though, Tupaia fulfilled at least part of his own dream to travel the Pacific once more.

Mai’s fierce determination to join Cook

Banks was not on Cook’s second voyage, but the captain carried with him the memory of the naturalist’s hopes to study a Pacific islander.

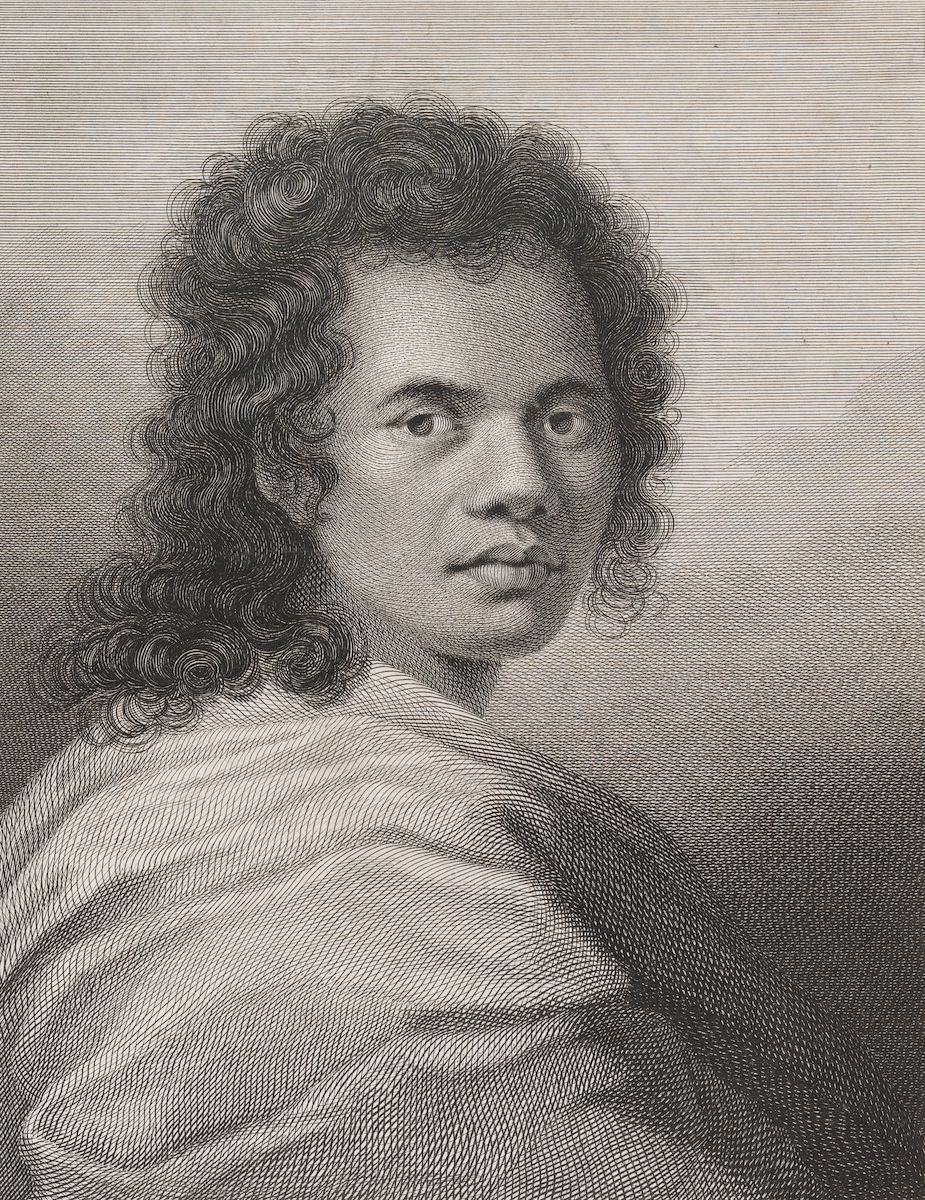

As I recount in my latest book, The Warrior, the Voyager, and the Artist: Three Lives in an Age of Empire, Cook found that man when he encountered Mai in 1773.

Like Tupaia, Mai was also displaced by the Bora Boran invasion of Ra‘iatea. A generation younger than Tupaia, Mai had been a child at the time and also lost his father in the conflict. In Tahiti, his lower social rank meant he had fewer concessions as a refugee.

Arguably these conditions made Mai even more determined to join Cook’s expedition when the chance came.

Mai travelled to Britain on Cook’s second ship, captained by Tobias Furneaux. The Englishman admired Mai and remarked several times on his maritime and culinary skills. Mai also helped translate and mediate with other islanders they encountered. This wasn’t because he sympathised with the British; rather, he was eager to speed up their return to Britain.

Mai’s mission in London and return home

Arriving in London in 1774, Mai met with Banks, who assumed responsibility for his accommodation. Due to his high-profile patron, Mai encountered and bedazzled much of the glamorous set in London, including King George III.

Mai seemed to enjoy himself well enough, but his mind was always focused on his larger mission. Everyone who met him recorded that his aim in Britain was not to impress or assimilate but to gain support for his mission of retaking his home island of Ra‘iatea from the Bora Borans.

Mai found himself aboard Cook’s third voyage to the Pacific in mid-1776, with promises from Banks and the Admiralty to take him home and provide him with British goods to help him achieve his goals.

Once again, he provided critical assistance to the captain during negotiations with other Pacific islanders, as well as with Indigenous people in Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania). Only when the expedition neared the Tahitian archipelago did Mai start to doubt Cook’s good faith.

He saw Cook give away much of the livestock that had been promised to him and watched as he held long meetings with assorted elders. Mai realised Cook planned to dump him on another island rather than fulfill the Admiralty pledges to land him on Ra‘iatea.

Mai was devastated. After four long years away, his life project had collapsed.

Grand ambitions only partly realised

Historians like to recount the emotional farewell between Cook and Mai in late 1777, noting Mai’s desperate wailing and Cook’s misty eyes. It’s usually depicted as a touching example of how Mai had grown to love the British and, equally, of how Cook had a softer heart than most believed.

From Mai’s perspective, though, the moment likely had a far different meaning.

Neither Tupaia nor Mai had achieved their ultimate goals in joining the Cook voyages, but this does not discount the grandness of their ambitions.

Both undertook epic feats of exploration. And their missions were just as political as Cook’s had been. Instead of imperial expansion, however, these men had sought a continuation of their Indigenous ways of life.

And it’s worth pointing out that Cook failed in his ultimate goal in the third voyage, too. He had been tasked with finding a northwest passage for imperial trade and to deliver Mai home according to his wishes. Instead, he ended up assassinated in Hawai’i.

– ref. The stories of Tupaia and Omai and their vital role as Captain Cook’s unsung shipmates – https://theconversation.com/the-stories-of-tupaia-and-omai-and-their-vital-role-as-captain-cooks-unsung-shipmates-126674