Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Philip C. Almond, Emeritus Professor in the History of Religious Thought, The University of Queensland

In classical Western theism, God is said to be both good and all-powerful. So how do we square natural disasters – global pandemics, earthquakes, tsunamis, famines, bushfires, and so on – with a God who, because he is good, would not want natural disasters and, because he is all-powerful, could stop them if he wished?

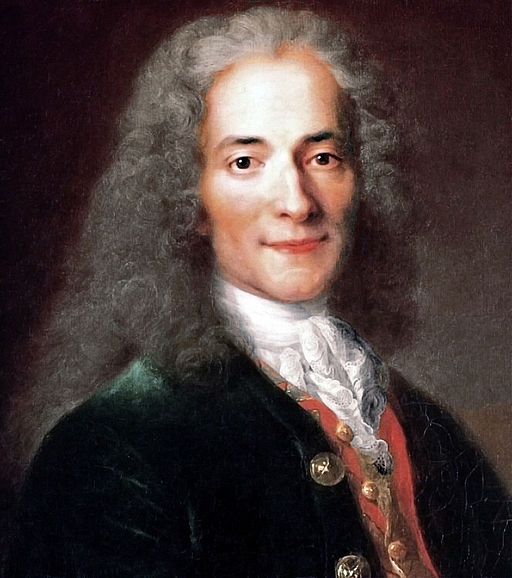

This was a question asked after the devastating Lisbon earthquake by Voltaire (1694-1778), one of the great philosophers of the European Enlightenment. It led to one of his most famous works: Candide, or l‘Optimisme (1759).

On 1 November 1755, at 9.30am, Lisbon in Portugal was almost totally destroyed by an earthquake, followed by further tremors, fires, a tsunami, and civil unrest. It was All Saints Day and large numbers of people were killed as churches collapsed upon them. Statistics for natural disasters, then as now, are notoriously rubbery. But between 20,000 and 40,000 people died out of a population of some 200,000.

Then, as now, people wondered whether there was a divine plan to the devastation that shook their Christian beliefs and monuments.

Read more: Are you there God? Whether we pray harder or endure wrath depends on the religious doctrine of Providence

Beyond the appearance of evil

In writing Candide, Voltaire had the German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) in his sights and especially his essays on the goodness of God in Theodicy (1710). For Leibniz, in spite of evils both natural and moral, this was still the best of all possible worlds. It was the best that God could have made. This was because it had both the greatest variety of things and the simplest laws of nature.

Evils both natural and moral, Leibniz declared, were part of an overall universal good. If the “smallest evil that comes to pass in the world were missing in it,” he declared, “it would no longer be this world; which, with nothing omitted and all allowance made, was found the best by the Creator who chose it”.

While Leibniz admitted it was possible to imagine worlds without sin and without unhappiness, “these same worlds would be very inferior to ours in goodness”. God was, in other words, the perfect gardener in spite of the cosmic weeds.

Before God created this world, according to Leibniz, he compared all possible worlds in order to choose the one that was best. Thus, God created a world that was all the more harmonic for some pain, acidity, and darkness rather than being all pleasure, sweetness, and light.

Leibniz wasn’t stupid. He saw that the “appearances” of evil in the world strongly cut against God’s goodness and justice. He refused, however, to allow the evils of the world to count decisively against God. This would be to confuse the surface of the world with its depth.

He believed that the defender of God should proceed from a faith that the world, in spite of its obvious evils, was ultimately good by virtue of its foundation in the goodness of God who had, after all, created it.

Candid comedy

Did Leibniz’s unfailing 18th-century optimism and firm belief in divine goodness fail to take evil seriously? Voltaire thought so. In fact, Voltaire flipped the serious nature of evil on its head; believing that natural and moral evil were so serious they could only be treated satirically.

In Candide, Leibniz was cast as Dr Pangloss, an instructor in “metaphysico-theologico-cosmoloonigology” in the court of the Baron of Thunder-ten-Tronckh.

Pangloss was a committed believer in this world as the best of all possible ones, in spite of its natural evils and the moral evils perpetrated in particular by those of religious faiths (Christians, Jews, and Muslims). Whatever happened in the world, Pangloss, like Leibniz, was able to rationalise it as compatible with its being eventually for the best.

Voltaire found this notion of the best of all possible worlds problematic, given the sheer quantity and quality of evil present in it.

This system of All is good represents the author of nature only as a powerful and maleficent king, who does not care, so long as he carries out his plan, that it costs four or five hundred thousand men their lives, and that the others drag out their days in want and in tears. So far from the notion of the best of possible worlds being consoling, it drives to despair the philosophers who embrace it. The problem of good and evil remains an inexplicable chaos for those who seek in good faith.

Read more: Thoughts and prayers: miracles, Christianity and praying for rain

Carrying on

What was Voltaire’s solution? Surprisingly perhaps, it was not despair. Rather, it was a gentle resignation, a philosophical que sera, sera. This meant the quiet cultivation of our gardens as God had originally intended for us in the first Garden of Eden. We were to be like Adam and Eve.

There was to be, therefore, an avoiding of airy philosophical speculations on how to justify the ways of God to man (like this piece of writing is). Instead, Voltaire advocated doing a little good in the hope of our becoming a little better.

This is a solution that may not satisfy believers in the goodness of God. But it will resonate amongst those of us who, in isolation at home, are quietly tilling the soil, labouring in our vegetable patch, or contentedly mowing our lawns. Simple, but somehow satisfying!

– ref. Is God good? In the shadow of mass disaster, great minds have argued the toss – https://theconversation.com/is-god-good-in-the-shadow-of-mass-disaster-great-minds-have-argued-the-toss-137078