Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Tony Blakely, Professor of Epidemiology, University of Melbourne

Australia is on track to flatten the curve of coronavirus cases, which will allow our health system to cope with increasing demand for intensive care unit (ICU) beds, recently released modelling confirms.

The modelling, produced by the Doherty Institute, was delivered to government in February but only released publicly yesterday.

In a press conference before the release, Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Chief Medical Officer Brendan Murphy emphasised the modelling was theoretical and used international data.

International data is still useful – the public health advice on tobacco, for example, is derived mostly from non-Australian studies.But the way an epidemic plays out is context-specific. The way Australians hang out together, for instance, is different from the way Chinese people socialise. This changes fundamental parameters, such as how many people someone with COVID-19 can be expected to infect.

So what does the modelling tell us and what are we yet to determine?

What scenarios were modelled?

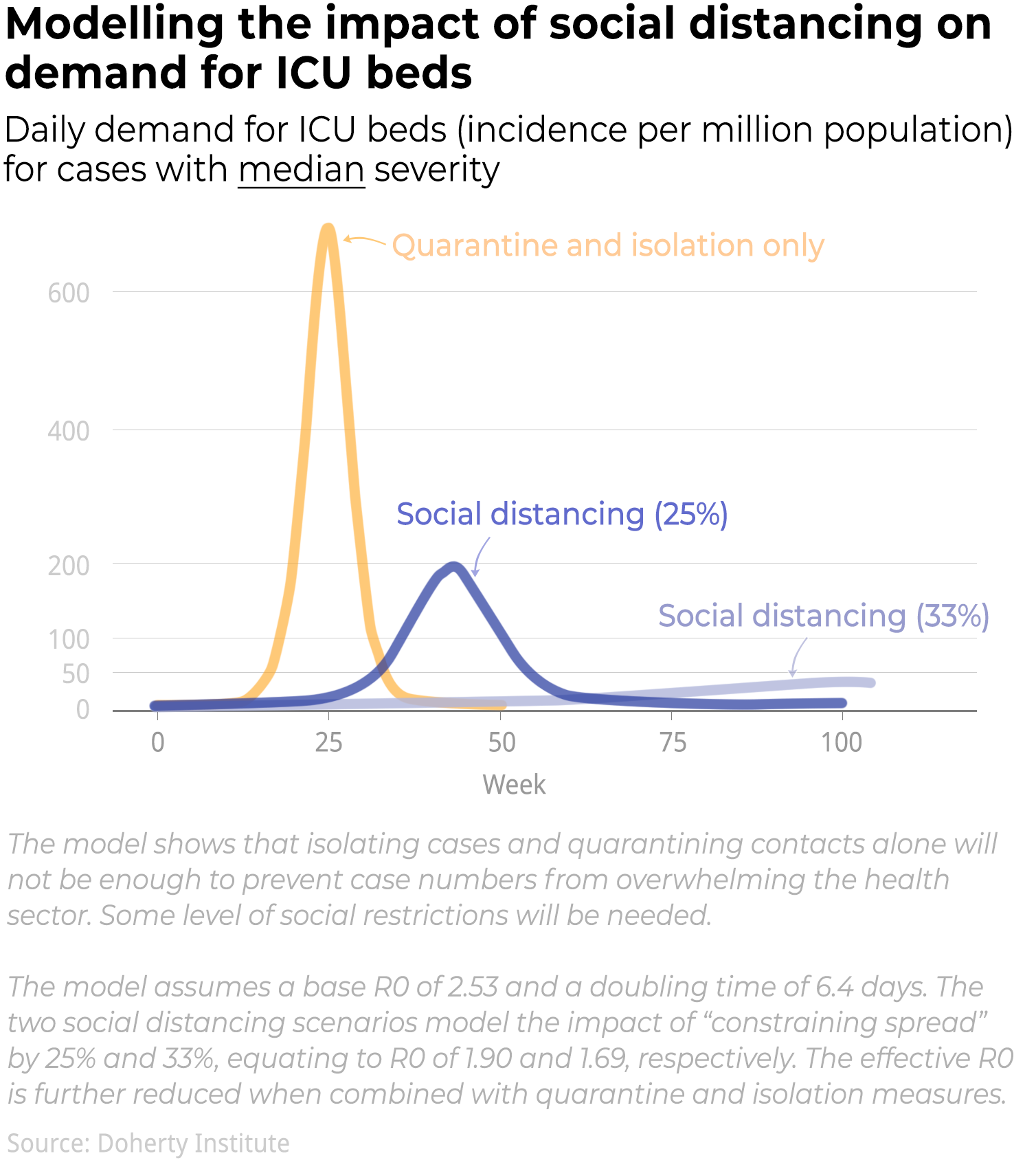

The more applicable of the two papers released yesterday aimed to estimate how much ICU and hospital capacity would be exceeded (in both percentage terms, and number of days) for various scenarios of how the epidemic unfolds.

The three scenarios were:

-

unmitigated spread (just “let the epidemic rip”). Peak daily ICU demand would be 35,000 a day, greatly exceeding Australia’s expanded ICU capacity of 7,000 beds

-

quarantine and isolation of cases scenario. The number of ICU beds needed during the peak would be 17,000 a day, still exceeding Australia’s expanded capacity

-

a quarantine and isolation scenario, plus social distancing at two levels of intensity. Daily ICU bed demand would peak at below 5,000.

Australia was never going to allow unmitigated spread and has implemented quarantine and isolation of cases. And in terms of social distancing, Australia has already exceeded the measures in the paper’s more intense scenario.

What do we learn from the modelling?

As we’ve learnt over the past month from simpler models and back-of-the-envelope calculations, ICU capacity is under grave threat of overload for anything other than a carefully designed, tested and monitored package of case isolation, quarantine and physical distancing.

Physical distancing is essential to flatten the curve enough to avoid ICU overload if we elect to let this epidemic wash through society to achieve herd immunity.

Read more: Coronavirus: can herd immunity really protect us?

Importantly, in all scenarios primary care and general hospital ward capacity were never (even remotely) threatened.

Accordingly, and correctly, the chief medical officer emphasised it’s important that people with existing chronic diseases (such as heart and respiratory disease) keep getting routine medical check-ups, so their conditions don’t deteriorate and require hospitalisation down the track.

If someone experiences sudden shortness of breath or chest pain, they still should be ringing 000 and getting assessed.

Life goes on, as do the vast array of other threats to our health that we can mitigate. And we have the capacity to keep doing this.

Read more: If coronavirus cases don’t grow any faster, our health system will probably cope

What do we do next?

The bigger question is what comes next, and this wasn’t addressed in the modelling papers.

The prime minister and chief medical officer urged Australians not to relax their current social distancing actions.

But Morrison noted there was a financial and societal limit to endless mitigation. In other words, we need to get through this, but within sensible resource limits.

Read more: Scott Morrison indicates ‘eliminating’ COVID-19 would come at too high a cost

The government wants to use this position of “relative calm” to make decisions about where to next. As Brendan Murphy said:

We are on a life raft. We now have to chart the course of where we take that life raft. The National Cabinet wants considered advice on all the directions. We don’t have those answers yet.

How can modelling help us decide?

Essentially, we need different, better and more models than we saw yesterday. Some of this work for the government is underway and will be released in coming weeks. But we also need two things:

1. Agent-based modelling

This is modelling of individuals bouncing around society like balls in a pin ball machine.

Yesterday’s model used equations applied to groups of people. But it can’t easily model the impact of separate interventions, such as school closures versus reducing gathering sizes.

Agent-based models offer more options. If we know, for example, that citizen A reduces their social contacts with people from 15 contacts a day of more than five minutes duration within 1.5 metres, to two such contacts while working from home, then we can (and should) model that.

We need many different agent-based models from many different research groups. Australians aren’t going to stay in lockdown indefinitely so the more models and sources of information, the better.

Read more: Coronavirus: there’s no one perfect model of the disease

2. To broaden the scope of modelling

We need models that include more than just the COVID-19 transmission dynamics. We need models that weigh up the consequences of both the epidemic, and our potential societal cures to the epidemic.

There is a real risk the societal cure we choose may do more harm. Lockdowns, for example, cause drops in GDP and increases in unemployment. That feeds back on to changes in suicide and heart disease. We need to quantify that, and weigh it up.

What are the options going forward?

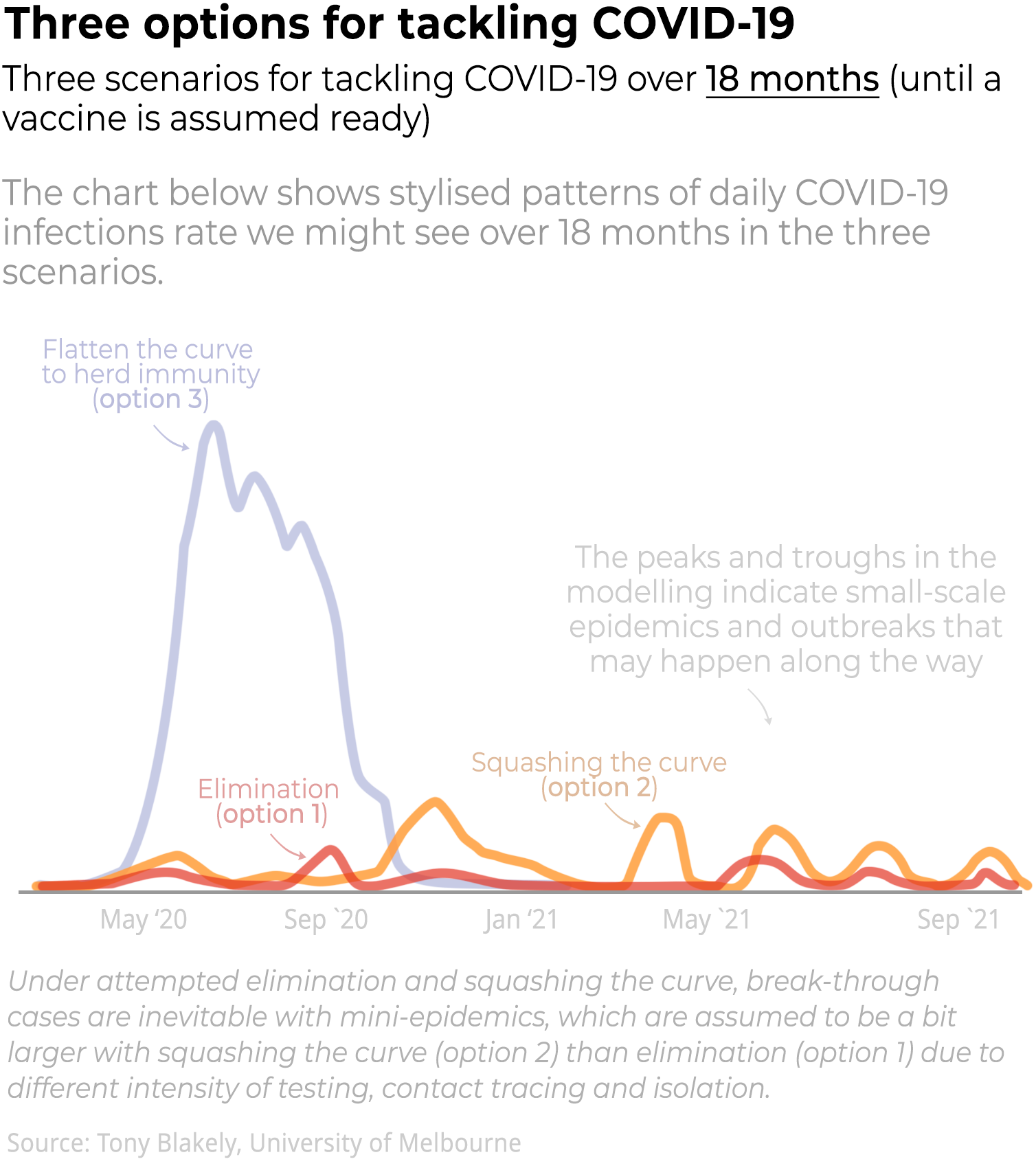

My team and many others around the country are building simple but useful models to help Australia decide on the way forward. There are three main options:

-

should we go all-in and aim for elimination (with the fall back of option 2 or 3 if this fails)?

-

should we keep squashing the curve, as we are doing successfully now, and wait 18 months for a vaccine?

-

should we meticulously plan for a relaxation of distancing measures (while protecting our elderly and those with chronic conditions), let the case numbers rise so our ICU can cope, and ride this flattened curve out to herd immunity within, say, the next six months?

This is what we need to work our way through.

Read more: Now we’re in lockdown, how can we get out? 4 scenarios to prevent a second wave

– ref. Yes, we’re flattening the coronavirus curve but modelling needs to inform how we start easing restrictions – https://theconversation.com/yes-were-flattening-the-coronavirus-curve-but-modelling-needs-to-inform-how-we-start-easing-restrictions-135832