Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Suzie Gibson, Senior Lecturer in English Literature, Charles Sturt University

The gothic developed as a European architectural phenomenon in 12th-century France, where awe-inspiring cathedrals reflected a world drenched in religious piety and superstition.

Its veneration was revisited in 18th-century English literature, when writers sought to inspire a comparable sense of wonder by setting scenes in ruined abbeys, haunted castles and spectacular natural landscapes.

Books like Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otranto (1764), Ann Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) appealed to a wide readership, but were dismissed as superficial sensationalism by the literary establishment.

The Australian gothic is unique from its northern counterparts. Instead of grand churches and castles, Australian writers dramatised remote towns, evoking a deep sense of malevolence operating beneath the veneer of ordinary life.

An Australian literary tradition

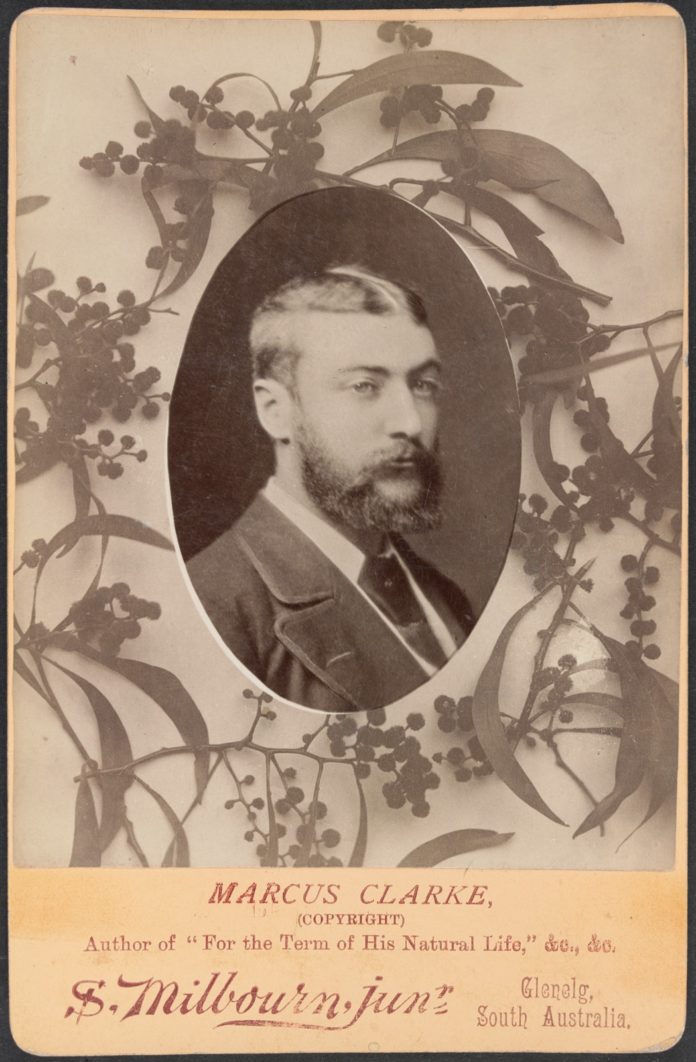

Rufus’s aristocratic identity is concealed as a testament to his fortitude and heroism. The plot’s many twists and turns centre on his efforts to escape from penitentiaries.

He is propelled by an abiding love for a young damsel whom he tries unsuccessfully to protect from ruthless villain Maurice Frere — his jailer and his cousin.

The Australian landscape features prominently. The harsh penal colonies of Macquarie Harbour and Port Arthur test the boundaries of human valour, Clarke critiquing a brutal convict system that demoralised and dehumanised.

Tasmanian readers rejected Clarke’s bleak vision of their isle, but For the Term of His Natural Life paved the way for other writers to explore the dark shadows amid the bright Australian light.

Barbara Baynton’s utterly devastating The Chosen Vessel (1896) reveals the depths of human malice. A mother is left alone to fend for herself and newborn baby while her husband works elsewhere. She is left vulnerable, and is raped and killed by a lone swagman.

In Baynton’s outback setting, male characters are not protagonists: they are antagonists who belittle and kill. Similar to Clarke’s hostile audience, readers were troubled by her grim vision.

Read more: Refuge in a harsh landscape – Australian novels and our changing relationship to the bush

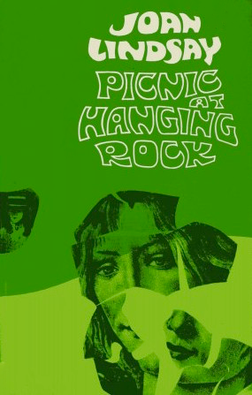

The most celebrated Australian gothic novel is Joan Lindsay’s Picnic at Hanging Rock (1967), telling the story of the inexplicable disappearance of a group of schoolgirls and their mathematics teacher.

Adapted for the screen by Peter Weir in 1975, Picnic at Hanging Rock plays on the gothic’s romantic sensibility by featuring a number of beautiful young women – pure Botticelli angels – stalked by monsters.

One such monster is the Australian landscape. The film, driven by Russell Boyd’s astute cinematography, suggests it was the rock itself that devoured the schoolgirls and teacher Miss McCraw.

The gothic aesthetic has been especially notable in Australian cinema.

Long Weekend (1978), Shame (1988), Wolf Creek (2005) and Van Diemen’s Land (2009) followed in the wake of Weir’s masterpiece. Astonishing landscapes entrap, stymie agency and foster humanity’s worst traits.

Across these texts is the singularly Australian fear of being lost in the bush.

In her book White Vanishing, Elspeth Tilley argues this fear resonates with white guilt about the attempted genocide of countless Indigenous peoples. Indeed, the gothic genre was a colonial import along with this genocide.

From silver screen to your headphones

The Oz Gothic podcast series, out now through the ABC, adds to this long line of a uniquely Australian gothic style.

Produced by Camilla Hannan, Oz Gothic features six distinctive stories by Tony Birch, Maria Tumarkin, Julie Koh, Lachlan Philpott, Alicia Sometimes and Krissy Kneen. Each contributes to this Australian history of gothic storytelling.

The stories traverse the suburbs to rural towns. We hear the voices of women, Indigenous people, and multicultural Australians.

Ordinary life can have an edge of malice. Some of the stories evoke Baynton’s bleak vision of women’s assault and murder. Others channel influences from Hitchcock to Wake in Fright (1971).

Nothing is exaggerated. The writers capture the truth of humanity’s vulnerability and, in particular, women’s exposure to male violence. The writers invest welcome strains of empathy and compassion for the disenfranchised and dispossessed: they are still the victims of crime, but here empowered to tell their own stories.

Read more: How to listen to podcasts

Oz Gothic astonishes in its deft use of sound: high heels echo on loud surfaces; guns discharge from attempted suicides; magpies chortle in small communities; lawnmowers drone and chainsaws buzz in suburban streets.

This pared-back power returns the gothic to its medieval origins, where acoustic language dominated over printed and visual forms.

In the wake of a long history, this new series takes the Australian gothic into new territory.

– ref. Podcast series Oz Gothic breathes new life into Australian gothic storytelling – https://theconversation.com/podcast-series-oz-gothic-breathes-new-life-into-australian-gothic-storytelling-131676