Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Nicholas Gruen, Adjunct Professor, Business School, University of Technology Sydney

We think of Gough Whitlam’s 1972-1975 government as the most radical in our postwar history, dedicated to its leader’s “crash through or crash” style. (In the end, he crashed.)

But Whitlam’s approach to Australian honours was bold only on the surface.

Imperial Honours were scrapped. Today it’s rare for Australia’s worthies to run around town being called “Sir Bruce and Lady So-and-So” or “Dame Raylene” by every Tom, Dick and Harry (or Sir Tom, Sir Dick and Sir Harry).

Prime Minister Tony Abbott briefly reintroduced the tiles “Sir” and “Dame” in 2014 but it didn’t end well. Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser had a (less controversial) go four decades earlier.

However when you look closely, it becomes clear that the Whitlam government didn’t so much change the old system as re-brand it.Read more: We’re awarding the Order of Australia to the wrong people

In the imperial days there was a hierarchy of awards, and although there was some correlation between your achievement and the level of the honour you received, where you already stood in the social hierarchy counted for more.

If you were out there selflessly contributing to your local community, you might eventually get an MBE (that’s a Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire).

If you got luckier and had made more of a splash, you might get an OBE. That made you an “Officer” of the order. Above that was the CBE, which made you a “Commander”.

We’ve had the hierarchy the wrong way round

At the very serious end of the spectrum, a prominent departmental secretary or businessperson might be made a Knight Commander, or a Dame Commander. They could call themselves Sir Bruce, or Dame Raylene.

If you were really special – say you were a governor-general or ex-prime minister or perhaps an internationally recognised scientist or a top business figure, you might become Knight Grand Cross of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, or Dame Grand Cross.

Still, in everyday life, you only got called “Sir Bruce” or “Dame Raylene”, so mostly it was only Sir Tom, Sir Dick and Sir Harry down at the club who knew you were a cut above them.

There were all manner of gongs to be won even above that for the very, very special, at which point the fancy dress came out and the fun really got going.

Ausralia’s longest-serving prime minister Robert Menzies couldn’t get enough of them.

On the death of the incumbent in the position (Sir Winston Churchill), the Queen invested him Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and Constable of Dover Castle, which included an official residence at Walmer Castle for his annual visits to Britain.

Under the new Australian honours system brought in by the Whitlam government, there were no more Sir Bruce and Lady So-and-So or Dame Raylenes. But virtually everything else was left intact.

What’s changed? The awards are more visible

Letters appear after people’s names if they want to use them, just as in the old days. But these days there’s a twist. No, I’m not talking about all the people who write “AM” on their Twitter profile. If you’re awarded an honour, in addition to the medal placed around your neck at the ceremony, you get a lapel pin.

Because all the honours get one and most seem to wear them around town, and not just at official functions, in some ways the new awards are more conspicuous than the old ones.

And the values that drive them are much the same.

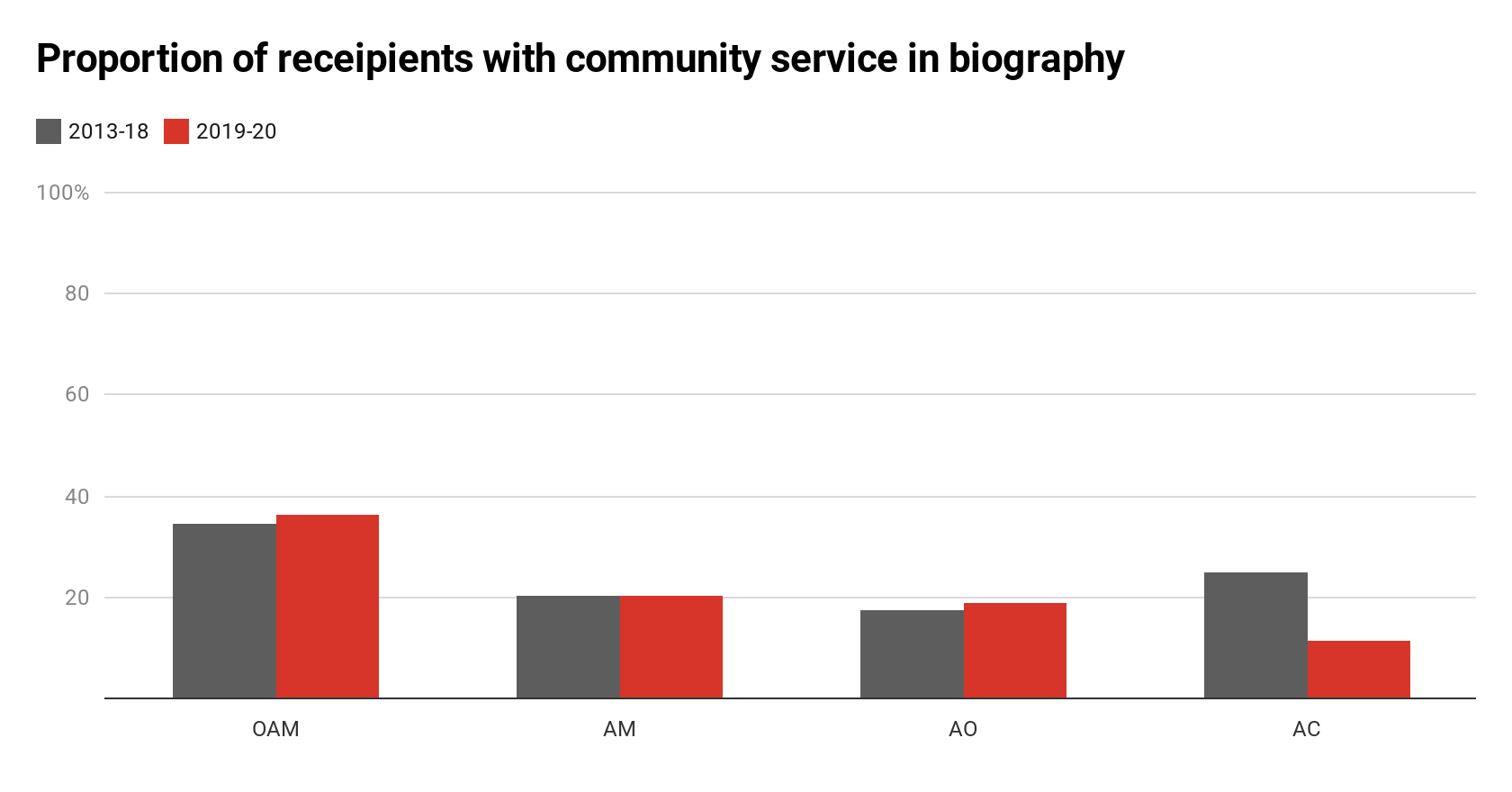

People in high-status jobs receive the overwhelming bulk of the high-status honours (ACs and AO). The low status orders go to people of lower status who are often doing good things in their own time rather than as part of their job.

Things are improving, a litle

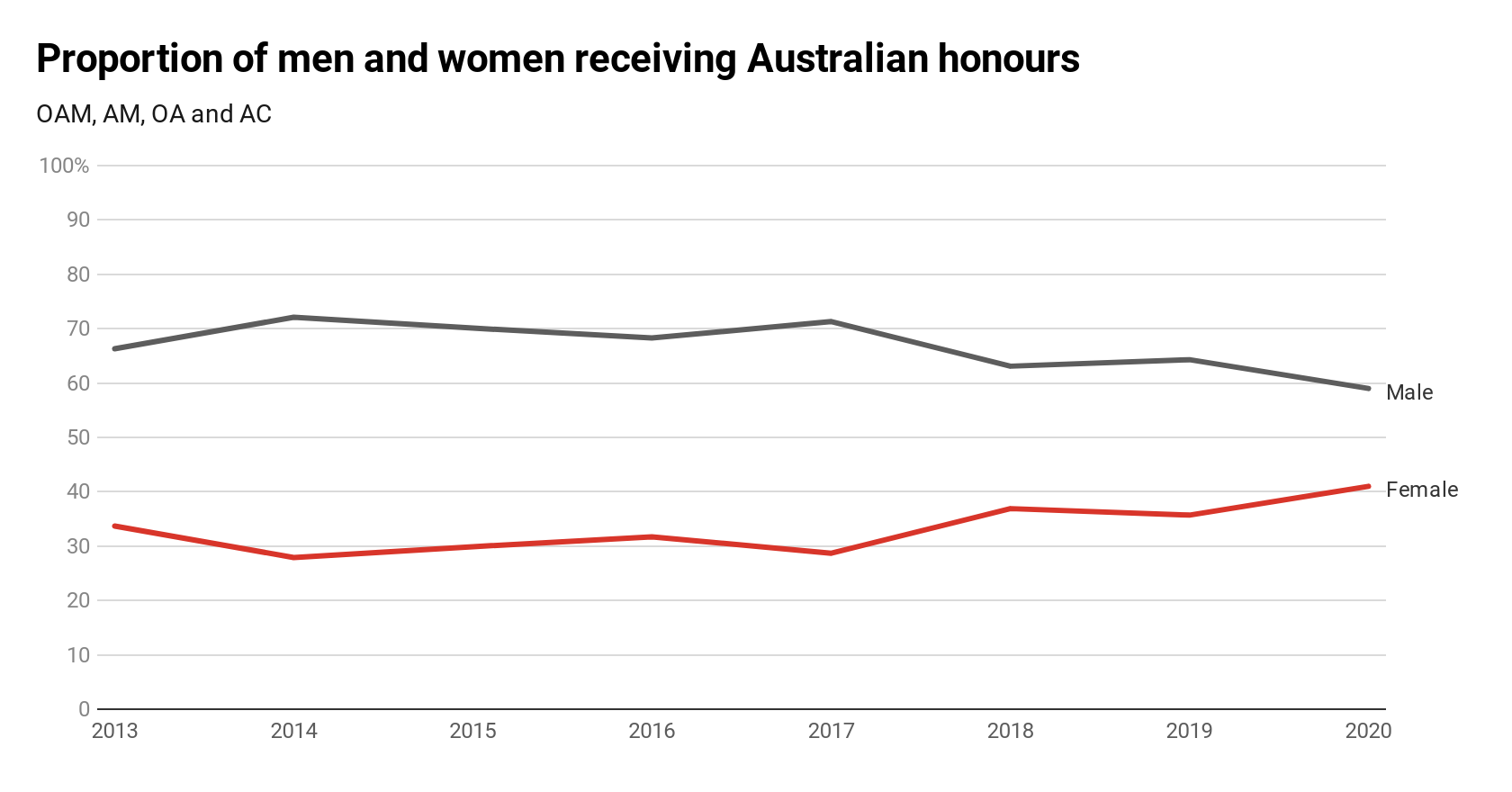

The under-representation of women seems to be improving, if very slowly. And it is unclear how secure the gains are, given that women’s under-representation increased quite sharply in 2014 and reached its recent zenith in 2017.

(I note it surged after the election of Coalition in 2013, but I’ve insufficient data at this point to be confident of trends.)

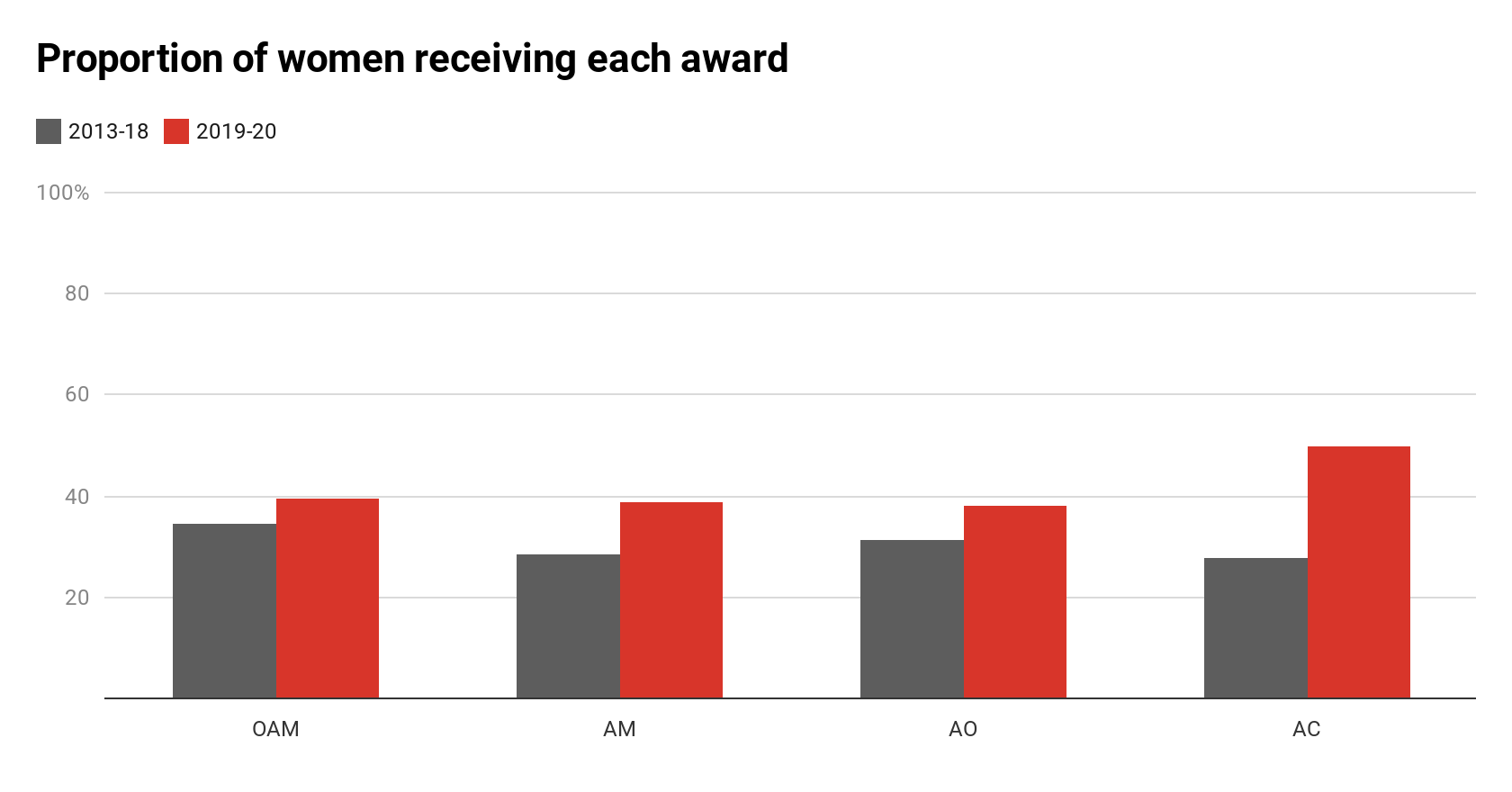

Last year I reported that, with the exception of the highest award (the AC, of which there are very few) women were substantially best represented in “lowest” award, OAM.

Since then the representation has become more even.

We also looked at how many honours went to those whose “official honours” biographies include work done without personal gain. (We excluded about 5% for reasons of data quality such as biographies being unavailable.)

Here, as you can see that, again with the exception of the volatile AC results, the more selfless you are, the lower in the hierarchy your award is likely to be. There is no sign of change.

Thanks to Shruti Sekhar for research assistance

– ref. Whitlam didn’t really end our old honours system. We’re still handing Orders of Australia to the wrong people – https://theconversation.com/whitlam-didnt-really-end-our-old-honours-system-were-still-handing-orders-of-australia-to-the-wrong-people-130800