Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By John Hawkins, Assistant Professor, School of Politics, Economics and Society, University of Canberra

In 2017, Toni Watson was busking on the streets of Byron Bay. A couple of years later, using the moniker Tones and I, her song about that experience would become the world’s most played track.

Dance Monkey has now been streamed a billion times. It was the most popular track last week in Israel, Malaysia and Switzerland and has been in Spotify’s top ten in over 50 markets.

Yet, this kind of global chart success is largely confined to English lyric hits. Despite the changes to music access, pop songs lag behind other industries in globalisation – particularly in terms of the language in which they are sung.

Dancing in the Streets

As economist John Maynard Keynes noted, stable international relations lead to trade globalisation. This is evident in a number of leisure fields.

Annual global tourism increased from under 1 billion to 1.5 billion arrivals over the past decade. Football club Manchester United claims to have 9 million Chinese followers. Globalisation can also be seen in diverse food offerings on menus around the world.While once music only ever moved as fast and far as musicians could travel, technology has uncoupled music from live performance. Musical notation, recording and now streaming platforms have rendered music and its flow limitless and instantaneous; characteristics only intensified by music’s digitisation.

Yet, the flow is something of a one-way street. English language acts are popular globally but songs in languages other than English rarely chart in the Anglophone countries.

There are plenty of hitmakers from non-English-speaking countries – Abba, Ace of Base, A-Ha, Aqua and Avicii are just the artists starting with A from Scandinavia who had number one hits in both Australia and the UK. But they primarily sing in English.

There have even been more UK number ones in Latin than in most modern languages, thanks to Enigma’s 1991 hit Sadeness (Part 1) and their album MCMXC a.D.

In the UK only ten of the over 1,300 number one singles since 1953 have been sung in a language other than English. Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin’s sultry song Je t’aime…moi non plus was the first in 1969, despite being banned as too risqué on some radio stations.

The most recent was Psy’s Gangnam Style mostly in Korean in 2012; and Luis Fonsi and Daddy Yankee’s (with Justin Bieber) Despacito partly in Spanish in 2017.

Australia has been even more monolingual, with only eight number one singles in languages other than English. Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s playlist appears to be quite typical.

The ostensibly cooler Triple J audience once again found no room for international tracks not sung in English in this year’s Hottest 100 – but there were two by Baker Boy who employs some of his Indigenous language Yolŋu Matha.

There has been one chart-topping album in Australia in an Indigenous language – Geoffrey Yunupingu’s Djarimirri in 2018 – and a notable (but not number one) single in Yothu Yindi’s Treaty in 1991.

While more Australians speak Asian languages than speak French or Spanish, songs in Mandarin, Cantonese or Japanese remain relatively unknown on Australian music charts.

By contrast, in Switzerland the Beatles, Abba, Madonna, Eminem and Rhianna have all made it to number one more than five times.

Sticky music

Asian language albums are starting to chart more in the West and pop music can be a portal to gain understanding of Asian cultures. The success of Gangnam Style opened charts for more typical K-Pop, with English snippets or a dance hook.

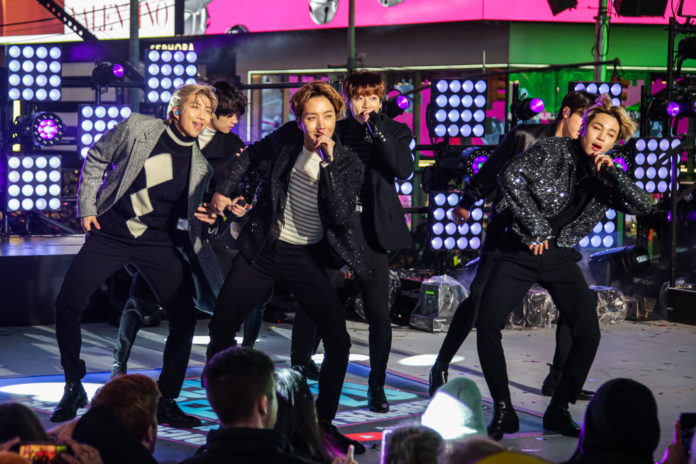

South Korean boy band BTS, who sing mostly in Korean, topped the album charts in Australia, the UK, Canada, New Zealand and the US with Map of the Soul: Persona. BTS performed (briefly) with US stars at the recent Grammys.

Though no BTS, Korean girl group BlackPink made the listings with their album Kill This Love. Japan’s Babymetal brought their mix of J-Pop and heavy metal on Metal Galaxy to the Anglophone album charts.

But all these acts were outshone and outsold by US singer Billie Eilish, whose debut album When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? not only topped the album charts in the Anglosphere but also in 15 non-Anglophone markets.

Read more: Billie Eilish and the female singers challenging James Bond’s machismo

Radio Ga Ga

There are now many more ways to consume music than buying singles, albums or listening serendipitously to the radio. While there may be the potential for a diversification of music consumption, the one-way street seems to continue.

Dance Monkey is near the top of the most played music videos from YouTube – which now represents a significant means of music distribution in its own right. There is also a linguistic asymmetry evident here. The top ten videos are all in English in the UK, and almost all in Australia, New Zealand and the US. But music fans in many non-English speaking countries find room for artists such as Tones and I, Billie Eilish, Eminem and Justin Beiber.

Pop music has a long way to go to be reflective of global diversity. But a balance is needed. Too much convergence and national musical cultures may be undermined; too little musical exchange would mean being unable to enjoy musical sounds from around the globe.

Spotify claims to herald “music’s most radically democratic era”. But the way it directs customers to songs similar to those they already like may encourage monolingual consumption of pop music rather than reverse this trend.

– ref. BTS are winning hearts the world over – but we are still wary of language diversity – https://theconversation.com/bts-are-winning-hearts-the-world-over-but-we-are-still-wary-of-language-diversity-130133