Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Sue Rabbitt Roff, Researcher, Social History/Tutor in Medical Education, University of Dundee

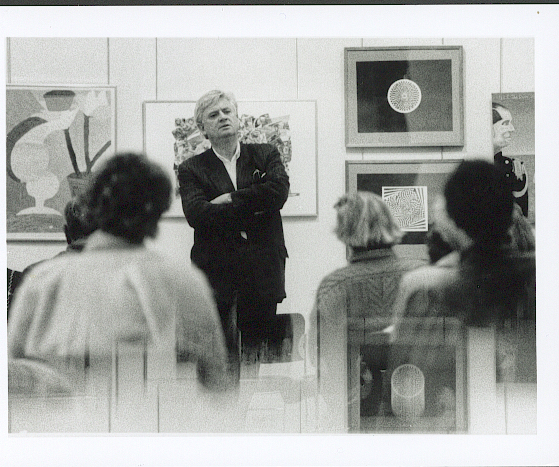

James Mollison, the founding director of the National Gallery of Australia, died on Sunday at the age of 88. He was a pivotal force in Australian art collecting, believing Australian galleries should work to educate both the public and our artists.

Mollison was born in Wonthaggi, Victoria, in 1931. When he left school in the late 1940s he approached the National Gallery of Victoria for what we would now call an internship.

He was taken on by Dr Ursula Hoff, who had just been given a permanent position at the NGV as Keeper of Prints after six years on temporary contracts. Mollison wrote in his personal tribute to Hoff in 2014:

Many of us at the Australian National Gallery have sought Dr Hoff’s opinion, drawing on a tradition of teaching that I know has continued for forty years.

A great gallery for the nation

It is a fair bet Mollison attended Sir Kenneth Clark’s lecture on The Idea of a Great Gallery at the NGV on January 27 1949.The British art historian was a great admirer of Hoff, and her promotion was largely due to his power to make or break careers – his letters supporting her are in the Tate Archive in London.

Clark spent the war years making the National Gallery on Trafalgar Square – founded in 1824 – a truly public space for Britons and others to see and learn about art, despite the Blitz.

In his Melbourne lecture, Clark urged the gallery to purchase experimental work, saying: “[This] seems to me particularly necessary in this country, where you have a young and vital and adventurous school of painting.”

To “guide and stimulate” Australian artists, he said, they needed:

[…] a sight of the best modern work, something which still has about it the thrill of experiment. They are trying to discover a fresh way of seeing, and they must be allowed to study the work of those European and Latin American artists who are doing the same.

Following his informal internship with Hoff, Mollison trained as a secondary school teacher, becoming an education officer at the NGV in 1960. After a short stint at the NGV, he became a bureaucrat with the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board, working under three prime ministers – Gorton, McMahon and Fraser.

During this time, it was decided to build a national art gallery in Canberra – a building which had been long advocated for. It is an indication of the respect in which he was held that Mollison was appointed acting director in the 1970s.

Finally, with the endorsement of Fraser, he was confirmed as full director in 1977.

1973

1973 was a particularly memorable year for Australia’s accumulation of cultural capital: Patrick White won the Nobel Prize for literature on the same day the Queen opened the Sydney Opera House.

In Canberra, Mollison was authorised by Prime Minister Whitlam to pay A$1.3 million for Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles: then the highest price ever for a contemporary work of American art.

Blue Poles still hangs at the NGA, where it is now speculatively valued at A$350 million.

Read more: Here’s looking at: Blue poles by Jackson Pollock

It seems Mollison was following Clark’s advice to buy experimental art to educate Australian artists. Prior to the opening of the gallery, Mollison also collected works such as Woman V by Willem de Kooning, Sidney Nolan’s Ned Kelly series, and significant works by Arthur Boyd and Albert Tucker.

My research has traced the purchase of Blue Poles by Mollison and his colleagues through connections to the London gallerist Bryan Robertson, another of Clark’s proteges, who promoted both Australian artists and Jackson Pollock by exhibiting them at the Whitechapel Gallery in London.

Barely a year after the sale, Robertson was offered the position of associate director of the NGV, given without an interview on the basis of Clark’s reference. However, Robertson didn’t take the post because of his “dread, really. Of going off to the other side of the world.”

After Blue Poles

The controversy over the price paid for Blue Poles overshadowed Mollison’s directorship, but he continued to acquire both contemporary Australian art and overseas works with what was regarded as a good eye.

In 1990, Mollison left Canberra for the NGV in Melbourne, where he stayed until 1995.

The NGV is now 22nd on the list of the world’s most visited art museums. More than 2.5 million cross its doorstep each year. Despite Blue Poles and the Ned Kellys, the NGA comes in 86th, with 928,000.

When I interviewed the American art collector Ben Heller in 2018, he said one major reason why he sold Blue Poles to the Australians was they promised him:

No child could graduate [from school] without going to Canberra to see Blue Poles.

Even though Mollison started his career as a public art teacher, that promise seems to have been lost – although the painting did tour Australia (complete with armed guard) before being put in storage to wait for its gallery to be built.

The acquisition of Blue Poles divided the art world and the Australian public who paid for it. But certainly it was an educational exercise, which was probably the legacy James Mollison wished to leave.

– ref. James Mollison: the public art teacher who brought the Blue Poles to Australia – http://theconversation.com/james-mollison-the-public-art-teacher-who-brought-the-blue-poles-to-australia-130285