About 175,000 New Caledonians will vote on the future of their Pacific territory this Sunday—a status quo French-ruled New Caledonia, or an independent Kanaky New Caledonia. What will be their choice? David Robie backgrounds the issues that led to the vote.

With New Caledonia facing the first of possibly three referendums on independence on Sunday—given the widely expected defeat this time around, it is timely to reflect on the turbulent 1980s.

An upheaval known locally by the euphemism of “les evenements” led to the 1988 Matignon and 1998 Nouméa accords as a compromise solution for indigenous Kanak demands for independence back then and the power sharing that has evolved for the past three decades.

The climax is with this Sunday’s vote, but if the status quo remains the accords provide for a further two referendums in 2020 and 2023.(1)

READ MORE: Asia Pacific Report coverage of the referendum

NEW CALEDONIA OR KANAKY?: THE INDEPENDENCE VOTE

NEW CALEDONIA OR KANAKY?: THE INDEPENDENCE VOTE

When the Pacific was still in the grip of Cold War geopolitics, France claimed that it wished to retain its South Pacific presence for similar reasons to the United States—a concern about communism and the old Soviet Union, the desire for stability and the maintenance of the “balance of power”.

But there were other, more sinister, factors behind the publicly stated reasons. French colonialism in both New Caledonia and Tahiti in the 19th century was largely motivated by the wish to prevent the South Pacific becoming a “British lake”. (2)

New Caledonia became the most critical factor in this political equation. When Vanuatu became independent from Britain and France in 1980, France’s then State Secretary for Overseas Territories, Paul Dijoud, pledged that “battle must be done to keep New Caledonia French”.

New Caledonia was at that time the last “domino” before French Polynesia where the vital nuclear tests for the force de frappe were still being carried out until they ended in 1996.

Revolt, assassinations

It is in this context that the 1984 Kanaks revolted against French rule, which eventually cost 32 lives—most of them Melanesian, with the Hienghène massacre the most devastating early clash and culminating in the assassinations of independence leaders Jean-Marie Tjibaou and Yéiwene Yéiwene on 4 May 1989.

Within eight weeks of the start of the rebellion, militant Kanak leader Éloï Machiro, who had bloodlessly captured the mining town of Thio, was dead—shot by French police marksmen. From then on nationalist tensions in New Caledonia rapidly became convulsions, spreading throughout the South Pacific and culminated in the Ouvéa cave massacre on 5 May 1988 with the brutal death of 19 young militants and two French security forces. (3)

The New Caledonian events led to my 1989 book Blood On Their Banner: Nationalist Struggles in the South Pacific (4) and the shocking story of the Ouvéa hostage-taking saga and its savage climax was told graphically in Mathieu Kassovitz’s 2011 film Rebellion (l’Ordre et la morale).(5)

A report by CIGN hostage negotiator Captain Philippine Legorjus, who had tried valiantly to achieve a peaceful end to the crisis, said: “Some acts of barbarity have been committed by the French military in contradiction with their military duty.”

His report later became the basis of the controversial feature film’s script.

The following 1984 article, “Blood on their Banner”, one of my first while covering New Caledonia as an independent journalist through the 1980s, was published in the New Zealand Listener and later included in my 2014 book Don’t Spoil My Beautiful face: Media, Mayhem and Human Rights in the Pacific.(6)

***

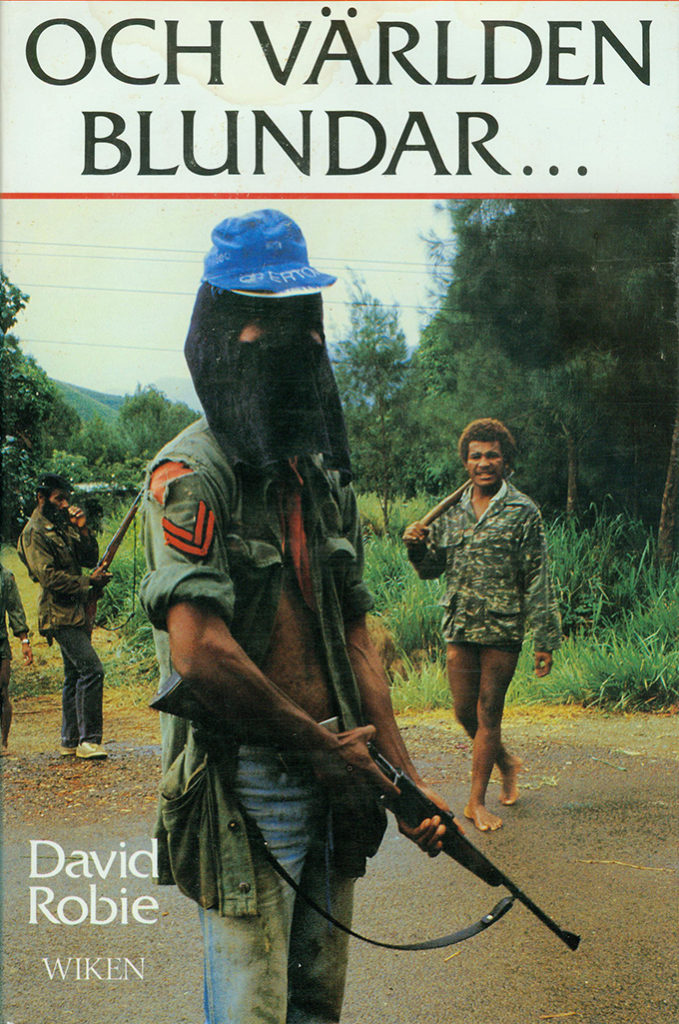

A masked Kanak militant near Thio, New Caledonia, 1985, on the cover of the Swedish edition of David Robie’s 1989 book Blood on their Banner. Image: David Robie/PMC

A masked Kanak militant near Thio, New Caledonia, 1985, on the cover of the Swedish edition of David Robie’s 1989 book Blood on their Banner. Image: David Robie/PMC

BLOOD ON THEIR BANNER

New Zealand Listener

27 October 1984

Leaders of New Caledonia’s independence movement say that time is running out. Their blood has already been spilt and they fear more bloodshed lies ahead.(7)

A new flag flutters defiantly from makeshift flagpoles in a handful of villages in New Caledonia. It is blue, red, and green-striped—symbolising the sky, blood and earth. A golden orb represents the rising sun.

This premature banner of independence was first hoisted in Lifou Island during an official ceremony recently marking the 44th anniversary of General de Gaulle’s call for a Free France.

Two flags … French tricolour and the Kanak ensign symbolising independence. Image: David Robie/PMC

Two flags … French tricolour and the Kanak ensign symbolising independence. Image: David Robie/PMC

Mayor Edward Wapae, of the ruling Independence Front, recalled that de Gaulle’s speech in 1940 showed a determination to “liberate France soil from the Nazi occupiers and to reconquer French independence, the principles of which had made her the home of the rights of man and liberties”.

In the next breath, Wapae said that the children and the grandchildren of the Kanaks (the largest single ethnic group in New Caledonia), who had fought for France then, were fed up with vain promises. He made a “last chance” plea for France to honour “her declarations condemning colonisation and defending the right of each people to decide their own future”.

The flags are just one manifestation of a growing mood of impatience and disillusionment among Kanaks demanding independence in the French-ruled South Pacific territory—New Zealand’s closest major Pacific Island neighbour. Another is the talk in villages of the “sacrifices” made by peasants during the Algerian war of independence.

French Pacific Regiment troops on ceremonial parade outside New Caledonia’s Territorial Assembly in Nouméa. Image: David Robie/PMC

French Pacific Regiment troops on ceremonial parade outside New Caledonia’s Territorial Assembly in Nouméa. Image: David Robie/PMC

South Pacific Forum leaders, meeting in Tuvalu during August [1984], again caution against putting too much pressure on France while urging that Paris speed up the colonisation process.

Take-it-easy attitude

Yet for the Kanaks, and neighbouring Vanuatu, this take-it-easy attitude is rather bewildering. “The Forum sees things the same way as the French socialists and our position—their Pacific brother—isn’t seriously considered,” complains Jean-Marie Tjibaou, who as Vice-President of the Government Council holds the territory’s highest elected post.

He has been particularly disillusioned with Australia and New Zealand, at least until Prime Minister David Lange’s sudden “reconnaissance mission” to Nouméa in early October.

Vanuatu’s Prime Minister, Father Walter Lini, also disappointed at the Forum’s lukewarm support, plans to press the New Caledonian case at the United Nations and try to get it reinstated on the so-called Decolonisation Committee’s list. He blames the Forum if violence erupts in the territory and fears “foreign opportunists may exploit the instability”.

The Independence Front, now renamed the Kanak Socialist National Liberation Front (FLNKS), recently decided to boycott and obstruct fresh elections due in the territory next month in protest against a new statute of autonomy.

Instead, the FLNKS has called its own parliamentary elections for November 11, planning to form a provisional government by December and renamed the country Kanaky.

Although the statute calls for a referendum on independence in 1989, the Forum believes this should be advanced to 1986—while the FLNKS wants independence next year.

Lini criticises the view, often expressed by Australia and New Zealand, that Paris has been doing all it could and should be given time to decolonise. “The history of French decolonisation frequently has not been peaceful … and no other South Pacific nation, apart from Vanuatu, has suffered it.”

Vanuatu’s ruling Vanua’aku Pati has made a revolution that opens the door for the FLNKS to form a government-in-exile in Port Vila. But Vanuatu’s government ministers are reluctant to discuss this and it is believed they would prefer a “people’s government to be with the people” in New Caledonia.

Hectic trip

In Tuvalu, Lange won support for establishing a five-nation Forum ministerial delegation—including New Zealand and Vanuatu—to visit Nouméa for talks with French authorities and the indépèndantistes.

After briefly flying to Nouméa and Port Vila at the end of his hectic trip, he stressed it was clear all New Caledonian political groups apart from the right-wingers wanted independence. He hoped to bring the factions together before the elections but his peaceful initiative may already be too late.

A Kanak girl in Nouméa’s Place des Cocotiers during a pro-independence rally in 1984. Image: David Robie/Tu Galala

A Kanak girl in Nouméa’s Place des Cocotiers during a pro-independence rally in 1984. Image: David Robie/Tu Galala

Why are the indépèndantistes taking this more militant stance when they are at present in the driver’s seat as the senior coalition partner in the government? “With the present colonial electoral system and past immigration policies, Melanesians are a minority in their homeland,” explains Vice-President Tjibaou, a 48-year old sociologist. “We cannot accept that logic. Now we’re putting a halt to it.

“We need a statute that will accept our logic—the logic of Kanak sovereignty.”

The bitter reality for New Caledonians, both brown and white, is that the French government has pushed through an autonomy statute that nobody wants. The Territorial Assembly in Noumea unanimously rejected the bill earlier this year. Justin Guillemard, leader of the extreme right-wing Caledonian Front, describes the law as an “administrative monstrosity” and “racist” in favour of Melanesians.

President Francois Mitterrand’s government, so keen to foster a strong middle ground, now seems further away than ever from any consensus among New Caledonians. And the Caldoche (settlers) are alarmed at the FLNKS’s determination to seek foreign help.

Wealthy businessman Jacques Lafleur, a deputy in the French national Assembly and leader of the Republican Congress Party which held local power until two years ago, denounced as “provocative” a visit by Tjibaou to Port Moresby in August when he lobbied an Asian-Pacific leaders’ regional summit. Lafleur also condemned a recent visit to Libya by two other Independence Front leaders.

Great admirer

The 51-year old Lafleur is a fifth-generation Caldoche and a great admirer of former Prime Minister Sir Robert Muldoon— “the only South Pacific leader who understands us”.

With an air of cynicism, he says: “Maybe there could be independence in 20 years or so, but it depends on what sort … I would never be a Kanak citizen. We are French people and the Kanaks are French too… One bad move and there will be blood in the streets.”

But for the Kanaks, blood has already been flowing in the streets and they fear more being spilt. French authorities have been quietly building up the strength of military forces in the territory to maintain order, if necessary. It is believed more than 4000 paramilitary and regular troops are now garrisoned there.

A French Pacific Regiment marine in a Nouméa military parade in the 1980s. Image: David Robie/PMC

A French Pacific Regiment marine in a Nouméa military parade in the 1980s. Image: David Robie/PMC

One MP, Yann-Celene Uregei, has a photograph in his office of his face battered and bleeding from the blows of a policeman’s truncheon at a protest rally during a previous French Government’s rule. Two years ago a group of extremist white thugs burst into the Territorial Assembly chamber and attacked pro-independence MPs. They received light sentences. There have also been sporadic riots.

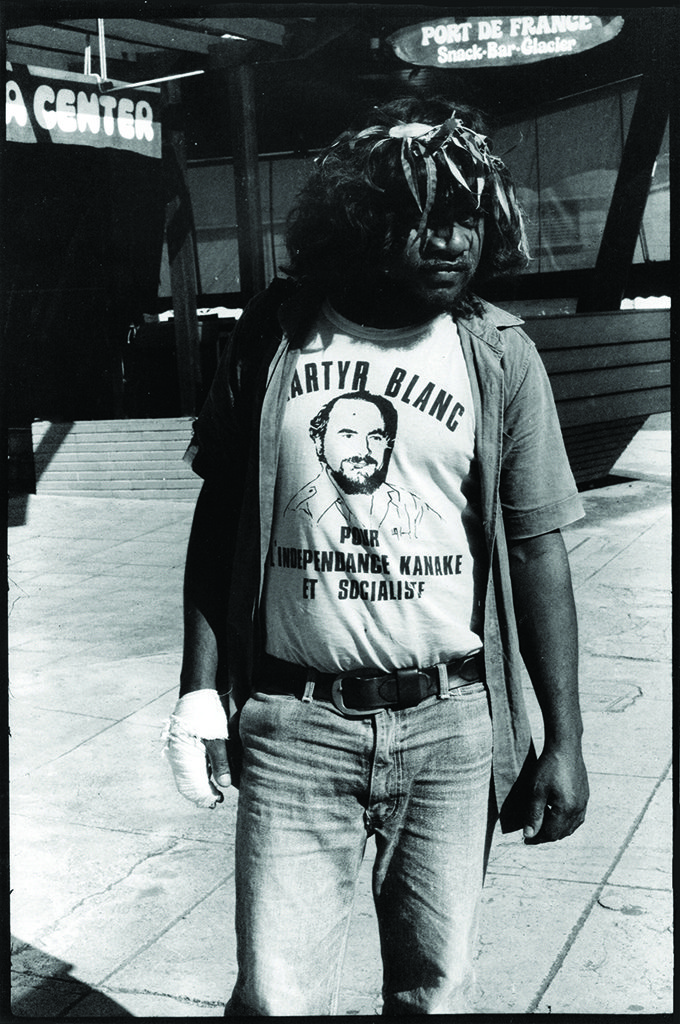

On the night of 19 September 1981, French-born Pierre Declercq, 43, secretary-general of the Union Calédonienne and a leading strategist of the Independence Front, was shot with a riot gun through the study window on his Mt Dore home. It was the first assassination of a South Pacific political leader. Now, three years later, nobody has yet been put in the dock for the murder.

During August more than 600 people marched on the Noumea courthouse demanding that a trial be held over the killing of “white martyr” Declercq, whose party was the key member of the FLNKS. Similar protest rallies were held in Poindimie, Pouebo, Voh and on Lifou Island in the Loyalty group.

Kanak wearing a “white martyr” tee-shirt honouring an assassinated early FLNKS leader Pierre Declercq. Image: David Robie/PMC

Kanak wearing a “white martyr” tee-shirt honouring an assassinated early FLNKS leader Pierre Declercq. Image: David Robie/PMC

A young motorcycle mechanic, Dominic Canon, was arrested and charged four days after the murder. Another man, Vanuatu-born barman Martin Barthelemy, was arrested a year later. But both suspects have been freed on bail.

Judicial delay scandalous

Marguitte Declercq accuses justice officials and gendarmes of obstructing inquiries into her husband’s killing; League of Human Rights secretary-general Jean-Jacques Bourdinat has called the judicial delay scandalous.

When I spoke to the cherubic-faced Canon, now 22, in his workshop on the outskirts of Noumea just after his release on $5000 bail from the notorious Camp Est prison, he insisted: “I’m innocent. They put me in jail for nothing.”

New Caledonia’s problem stem from its complex racial mix. Kanaks number only 60,000 out of a population of 140,000. About 50,000 Europeans form the next largest group, and the rest are potpourri of Vietnamese, Indonesians, Tahitians and Wallisians.

New Caledonia was annexed by France in 1853, mainly for the use as a penal colony. In three decades after 1860 more than 40,000 prisoners—including leaders of the 1871 Paris commune insurrection and other political exiles—were deported to the colony.

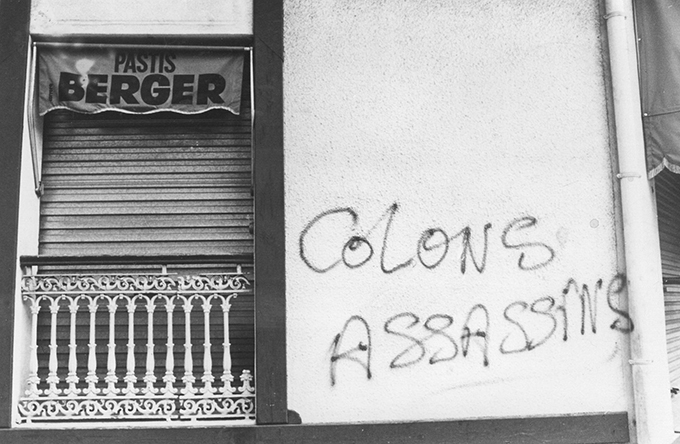

“Colonial assassins” graffiti denouncing French colonial rule in the Place des Cocotiers, Noumea, 1984. Image: David Robie/PMC

“Colonial assassins” graffiti denouncing French colonial rule in the Place des Cocotiers, Noumea, 1984. Image: David Robie/PMC

For almost a century the Kanaks were deprived of political and civil rights But after they finally won the vote in 1951, they begun to wrest a limited share of their own country’s development—which was later fuelled by a nickel boom.

According to Vice-President Tjibaou, the New Caledonian territorial government has less power now than during the controversial loi cadre years between 1956 and 1959, when the territory was almost self-governing. Later conservative French governments favoured policies which meant New Caledonia was governed as an integral part of France until the Mitterrand administration embarked on reforms in 1981—after the assassination of Declercq.

The indépèndantistes argue that the current French reforms, far from being progressive, have in fact only been restoring some of the progress made in the 1950s. And they fear that if the Socialists lose office in the French general election due in 1986 they will be faced with another stalemate. Hence their urgency for independence next year.

Unique style

They claim President Mitterrand betrayed a commitment to independence made before being elected, and again at a roundtable conference at Nainville-les-Roches last year.

The controversial statute will increase the Territorial Assembly from 36 seats to 42 (slightly favouring the indépèndantistes): create a unique style of upper house comprising custom chiefs and representatives of elected town councils; introduce six regional (Kanaks prefer the word pays, or cultural community) administrations; and establish a special commission to prepare the way for a referendum on self-determination in 1989.

Kanak villagers guard a barricade near Bourail, New Caledonia, 1985. The Kanak flag bears a red band representing the blood sacrificed in their struggle. Image: David Robie/London Sunday Times

Kanak villagers guard a barricade near Bourail, New Caledonia, 1985. The Kanak flag bears a red band representing the blood sacrificed in their struggle. Image: David Robie/London Sunday Times

“We haven’t any choice but to oppose the application of the statute,” says Tjibaou. “We must impose an ‘active’ boycott, because if we accept these elections under the statute of autonomy, we accept the colonial logic behind them.”

Tjibaou believes the election result would be insignificant and unrepresentative of the territory. Many FLNKS leaders consider that the French government couldn’t allow an unrepresentative local government, so they would annul the elections and be forced into making quicker concessions for electoral reforms.

French officials concede there could be a case for a qualified franchise, such as Fiji’s nine-year residential clause, but consider the FLNKS demand that voters should be only Kanaks or people with at least one parent born in New Caledonia to be “unconstitutional”. Fearful of eventual independence, white Caledonians are applying in droves for immigration permits to Australia. Wealthy New Caledonians are also buying lands in New Zealand’s South Island, California, Hawai’i, Queensland and the French Riviera.

Most Kanaks support the Independence Front, a coalition of five parties until the Kanak Socialist Liberation, led by charismatic Nidoishe Naisseline, split away recently over the election boycott decision. Naisseline, a Sorbonne-educated grand chief, says Kanaks “shouldn’t try to copy nationalist movements in Africa and Indo-China”.

The majority of Europeans back Lafleur’s Republican Congress Party which used to advocate continued integration with France. Now it is outflanked on the right by the Caledonian Front while the centrist Caledonian New Society Federation (FNSC), also mainly European, has been supporting the Independence Forum for the last two years.

New Caledonian politics is highly complex, and feelings are potentially explosive.

While the rest of the South Pacific—apart from Vanuatu, which was forced to cope with an abortive secession—peacefully gained independence, New Caledonia seems fated to break that pattern. Little wonder the indépèndantistes have included symbolic blood on their banner.

***

Ongoing conflict

Over the next seven years, I closely reported the ongoing conflict in Kanaky for Pacific and global media.

Multimillionaire mining and property mogul Jacques Lafleur, one of the richest men in France and the biggest thorn for Kanak independence, even though he eventually reluctantly signed the two critical accords paving the way for possible independence, died in 2010 aged 78.

He dominated New Caledonian politics for more than three decades, including 29 as a member of the French National Assembly.

Along with Jean-Marie Tjibaou—one of the great visionary Pacific leaders until he was assassinated in 1989 (7), Lafleur signed the 1988 Matignon accord and then the Noumea accord in 1998, and honoured a pledge to Tjibaou to open the way for a Kanak stake in the nickel mining industry.

Lafleur agreed to sell his controlling stake in Societe Miniere du Sud Pacific (SMSP) to the Kanak-dominated Northern Province government in 1990.

New Caledonian nickel is shipped to many Asian countries where it is processed to manufacture steel, electronics and consumer goods. The nickel industry has made many Caldoche wealthy, with minerals for 90 percent of the territory’s export revenue.

Criticism of the industry is highly unpopular with the establishment.

The Pacific Media Centre’s Professor David Robie is author of Blood on their Banner: Nationalist Struggles in the South Pacific and Don’t Spoil My Beautiful Face.

References

1. Haut-Commissariat de la Republique en Nouvelle-Caledonie (2018). Consultation sur l’accession a la plein souverainete de la Nouvelle Caledonie.

2. David Robie (1989). Introduction. In Blood On Their Banner: Nationalist Struggles in the South Pacific. London: Zed Books, p. 17.

3. Max Uechtritz (2018, May 7). Blood in the Pacific: 30 years on from the Ouvéa Island cave massacre. Asia Pacific Report.

4. David Robie (1989). Och världen blundar… kampen för frihet i Stilla havet [And the world closed its eyes – campaign for a free South Pacific]. Swedish trans. Margareta Eklof]. Hoganas, Sweden: Wiken Books; David Robie (1989). Blood On Their Banner: Nationalist Struggles in the South Pacific. London: Zed Books.

5. David Robie (2012). Gossana cave siege tragic tale of betrayal. Pacific Journalism Review: Te Koakoa, 18(2), 212-216.

6. David Robie (2014). Don’t Spoil My Beautiful face: Media, Mayhem and Human Rights in the Pacific. Auckland: Little Island Press./

7. David Robie (1984, October 27). Blood on their banner. New Zealand Listener, pp. 14-15

8. Sarah Walls (2009). Jean-Marie Tjibaou: Statesman without a state: a reporter’s perspective. The Journal of Pacific History. 44(2), 165-178.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz

]]>