Papua New Guinea threatened to temporarily ban Facebook earlier this year. With the APEC conference looming in November, the question remains whether this was an attack on freedom of speech. Jessica Marshall of Asia-Pacific Journalism reports in a two-part series on the Pacific internet.

In March, it was revealed that the data analytics firm Cambridge Analytica had harvested millions of Facebook profiles.

The breach, thought to be one of Facebook’s biggest, reportedly used the data to influence both the United States 2016 presidential election and the Brexit campaign in the United Kingdom.

In the aftermath, Facebook announced a commitment “to reducing the spread of false news on Facebook,” by removing false accounts and using independent third-party factcheckers to curb fake news on the site.

The effectiveness of this new policy remains to be seen.

The revelation of the Cambridge Analytica scandal lead to the Papua New Guinean government threat in May that it would ban the social network for a month in the country.

Communications Minister Sam Basil was reported by news media as saying the ban decision was an attempt to enforce the Cyber Crime Act 2016.

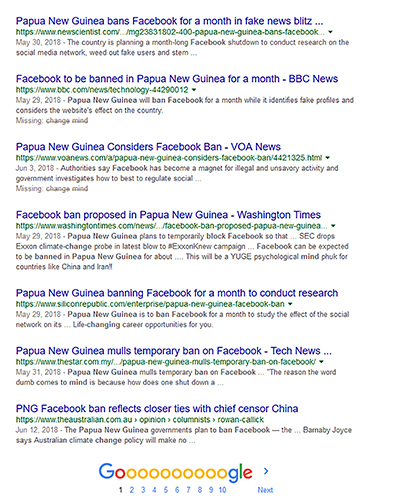

A horde of PNG “ban on Facebook” stories on Google, but stories on PNG’s subsequent back off in the proposal are hard to find. Image: PMC

A horde of PNG “ban on Facebook” stories on Google, but stories on PNG’s subsequent back off in the proposal are hard to find. Image: PMC

“The Act has already been passed, so what I’m trying to do is to ensure the law is enforced accordingly… We cannot allow the abuse of Facebook to continue in the country.” Basil told the Post-Courier.

Difficult to track

According to The Guardian, Basil had raised concerns about the protection of the privacy of Papua New Guinea’s Facebook users. He had claimed that it was difficult to track those who had posted defamatory comments on Facebook using “ghost profiles”.

Basil later denied in the media that he had said he would ban Facebook, but the Post-Courier stood by its report which had sparked of the flurry of stories and speculation. So far no ban has actually taken place.

Papua New Guinea is not the only country to have banned the social media site. Facebook is already blocked in authoritarian countries like China, Iran and North Korea.

In March, Sri Lanka blocked the site along with Viber and WhatsApp for nine days, believing it to be the cause of hate speech and violence.

Facebook was also condemned for allowing hate speech to become prominent in Myanmar during the Rohingya crisis earlier in the year.

The platform, according to Reuters, was claimed to have played an important role in the spread of hate speech when Rohingya refugees were fleeing their homeland to Bangladesh.

Other countries have made attempts to combat trolling and fake news, New Zealand included.

In 2015, New Zealand made cyberbullying illegal in an attempt to curb teen suicide. The law, passed in tandem with an amendment to the Crimes Act 1961, was designed to ensure that cyberbullies would face up to two years’ imprisonment.

‘Fake news’ conviction

In April this year, the Malaysian courts convicted its first person under a new fake news law. The Danish citizen was charged after he posted a video claiming that police were not quick to act after receiving distress calls regarding the shooting of a Palestinian lecturer.

Questions regarding free speech have circulated since the Basil reportedly made the announcement.

Only 11 percent of the Papua New Guinean population have access to the internet. The site, for those with the ability to use it, has become a news source in a place where media freedom is increasingly threatened.

PNG “news” blogs have proliferated.

While Freedom House’s most recent report on press freedom says that the press in Papua New Guinea is free, the organisation is quick to note that this freedom has become worse over recent years.

Freedom of speech, information and the press are all guaranteed and inalienable rights in Papua New Guinean law due to Section 46 of the country’s constitution.

What has caused problems, however, for the press is political pressure and violence. Over the years, journalists have been “detained without charge, and their video footage was destroyed”.

Three female journalists were sexually assaulted in 2014, the report states.

Reporters Without Borders also reported police violence against journalists in 2016. It said in a media statement that one NBC journalist had been assaulted by three police officers until another officer intervened. Others had been attacked by a plainclothes officer.

Facebook as news source

In the era of fake news, social media plays a huge role in how the people get their news.

According to Pew Research, two-thirds of American adults got their news through social media in 2017.

A report by the ABC said “more Papua New Guineans have access to social media than ever”.

“Facebook is… being cited as an important hub for news, and the audience is larger than other news websites with 53 percent of weekly users reporting the use of online social media compared to the two main newspapers’ websites,” the report said.

Daniel Bastard, Asia-Pacific director of Reporters Without Borders, said that blocking Facebook “would deprive nearly a million internet users” from news and information.

“Instead of resorting to censorship, the Communications Minister should encourage online platforms to be more transparent and responsible about content regulation.”

There is still concern about the upcoming APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) meeting in Port Moresby in November and a possible Facebook ban’s impact.

Paul Barker, director of the Institute of National Affairs, told the Post-Courier “It would be a travesty if PNG sought to close down Facebook during the APEC month… as it would be both an attack on embracing technology, undermining the information era and mechanisms for accountability, but also damaging business and welfare.”

Jessica Marshall is an AUT student journalist on the postgraduate Asia Pacific Journalism course.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz

]]>