AsiaPacificReport.nz

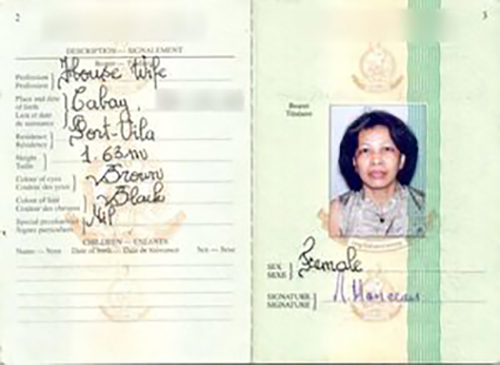

In her passport, Nesita Manceau lists her occupation as “housewife.” But she does oh-so-much more. On paper at least, she’s a corporate titan. And she’s been tangled in an arms-running scandal involving North Korea and Iran.

Manceau is what could be called a “zombie director” of shell companies. She’s been on the boards of scores of them. Lawyers in Florida, Oregon and Nevada have clients who call on her services.

The 55-year-old Filipina, who until recently was living in Vanuatu, exercises what is required of an offshore corporate director: She simply signs her name. Time and time again.

Practically the sole function of an offshore corporate director is to cloak the identity of the real owner of a company or trust.

The director serves as a legal shield, of sorts.

The documents known as the Panama Papers teem with these zombie directors who sign corporate papers at the bidding of unidentified owners.

Such directors can oversee, at least on paper, hundreds – and sometimes thousands – of corporations.

Crucial cog

They are a crucial cog in the machinery of foreign law firms and registration agents who churn out phantom corporations, stock them with proxy directors, slap a soothing name on them, and register them on atolls or far-away nations. It is a volume business.

True owners of the shell companies often want passive directors with no control over, or even knowledge of, actual operations. Secretaries, Burger King cooks and housewives will do.

Corporate registration agents like Mossack Fonseca, the Panama law firm whose 11.5 million leaked documents comprise the Panama Papers archive, earn extra fees when they stock the boards of offshore entities with nominees who usually have no clue as to the identity of the true owners.

“The fact is, if you waterboarded them, they wouldn’t come up with the name of the beneficial owner because they don’t know,” said Jack Blum, a Washington lawyer who has spent decades investigating money laundering and the use of offshore corporations.

But when government investigators come around trying to figure out who owns an offshore corporation, Mossack Fonseca offers up their names as if they had an actual financial stake and knowledge of operations.

That happened in 2011, when the director of the Financial Investigation Agency of the British Virgin Islands, Errol George, wrote to Mossack Fonseca inquiring about Fincom Trade Ltd. A company officer quickly responded.

“The Beneficial Owner of the company is Ms. Nesita Manceau whose address is: 1st Floor, Pacific Building, Port Vila, Vanuatu,” wrote J. Elizabeth Maduro.

‘See-no-evil’ directors

See-no-evil nominee directors are the mirror opposite of directors in the real corporate world, who usually have firsthand business experience that they use to hire and fire chief executives, oversee corporate decisions and protect shareholder interests.

The massive leak from the Mossack Fonseca law firm, shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and its partners, including McClatchy Newspapers, includes emails, copies of passports and financial records, which all cast light on the structures used in offshore companies, including the functionaries like Manceau.

Manceau was born in a remote Philippine hamlet called Cabay in Eastern Samar province. Her former husband said she once served as a housekeeper after moving to Vanuatu.

–]]>