AsiaPacificReport.nz

By Ati Nurbaiti in Jakarta

A national symposium on the Indonesian bloodshed of 1965 has brought together the persecuted, the persecutors and their respective families.

Seating positions at the tables were being rearranged until late at night before a recent symposium about the 1965 anticommunist violence.

No glasses were provided beside the bottles of mineral water, “lest participants throw glasses at each other”, one of the organisers, Ezky Suyanto, wrote on her Facebook account along with posted pictures of a big group of grinning participants of the National Symposium on 1965.

She added that, in any event, most of the participants were too old to throw glasses.

Police tanks were parked outside the Aryaduta Hotel in Central Jakarta, where the symposium took place on April 18 and 19, but most of the police, who were of a generation of the grandchildren of those who experienced the events of 1965, just snacked and chatted.

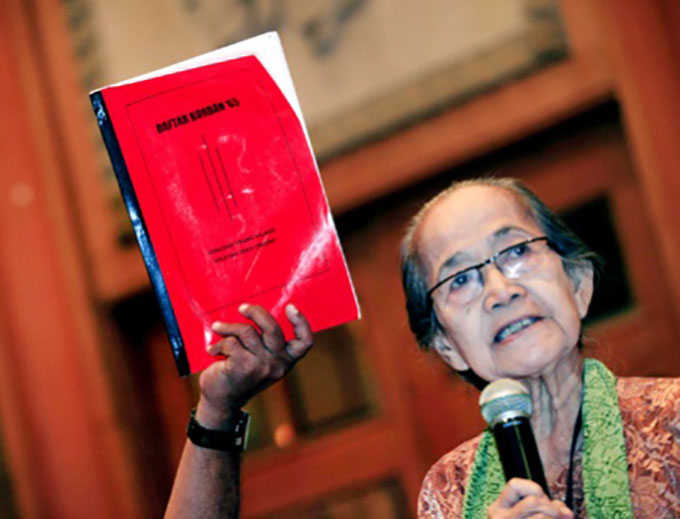

High-ranking officials have previously addressed the 1965 issues with survivors in talks held by national human rights bodies, but the opening of this official symposium saw the elderly survivors facing members of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s Cabinet, including Coordinating Political, Legal and Security Affairs Minister Luhut B. Pandjaitan, and National Police chief General Badrodin Haiti, along with Sidarto Danusubroto of the president’s advisory team.

The latter is a former adjutant of Sukarno, the country’s first president who was ousted following the coup attempt in October 1965 that was blamed on the now banned Indonesian Communist Party (PKI).

Old suvivors ignored

During the symposium Luhut blurted that the state “won’t go here and there asking for forgiveness […] I’m not that stupid”, ignoring the old survivors in the room and backing up what Jokowi had previously said, that “nothing has been decided” on the issue.

On the second day, a participant wondered why there were more victims than persecutors at the event. “Why are so many victims present?” he asked.

Behind that question was a deep sense of offence, since the people — including activists with Christian and Islamic student organisations — who went all-out on the communist witchhunt were told at the time they were heroes saving the nation, but now they are considered villains by those advocating for the survivors, who with their families have endured life-long stigma and discrimination.

Meanwhile survivors, many in their 80s, are still hurt and scared because they are now accused of seeking to “revive the PKI”.

So the packed ballroom brought together two “camps” — the persecuted, the persecutors and their respective families. “Actually, we’re all victims,” one said.

A few barking matches seemed enough to represent the pain felt on all sides. Former Christian activists, just like Islamists, said that around the time of 1965 they really feared the aggressive PKI and the looming powerful communists next door in Indochina.

Also, the military, as former local commander Sintong Pandjaitan told the forum, was indeed assigned to “safeguard” the countryside from communists.

‘Let bygones be bygones’

As everyone felt they were either innocent of crimes or a victim of them, or that they did what they had to do at the time, one proposed settlement was to “let bygones be bygones”. “Sing wis yo wis,” Harry Tjan Silalahi, a member of the former PMKRI Catholic students’ organisation, said in Javanese.

“That’s not for you to say. It’s the right of victims,” responded Ilham Aidit, the son of slain PKI leader DN Aidit.

Such statements, repeated 51 years later, had extra weight in the government-sponsored forum when they were uttered fearlessly. So amid officialdom and under the glare of staunch believers of the New Order version of 1965, the alternatives and counter-allegations were roared out:

“The ousting of Sukarno was a military coup!” shouted one of his daughters, Sukmawati Soekarnoputri, standing with clenched fist, to loud applause. “Bung [brother] Karno should be the first to be rehabilitated!” said historian Asvi Marwan Adam.

The founding father, who had named himself president for life, is still blamed for his indirect role in facilitating the PKI’s rise to power.

The witchhunt and killings were “a political genocide!” shouted an organiser of the recent International People’s Tribunal on 1965 held in The Hague. Reza Muharram was reacting to insinuations that the tribunal organisers were “selling out the country” to international donors of NGOs.

“That Gerwani sliced off the general’s penis is a lie!” shouted a former member of the women’s organization affiliated to the PKI about a scene in the government propaganda film called G30S/PKI. The Gerwani became known as an “immoral” group based on decades of propaganda about their role in the generals’ murders.

‘No horizontal conflict’

“It’s no horizontal conflict when violence lasts for months across many areas,” said Ariel Heryanto, who was among the rebellious scholars under Soeharto. He said the conflict “shifts the responsibility of the state to civilians”.

Dealing with the 1965 atrocities, the government states, will be the “gateway” to settle other major abuses and controversy surrounds where that gateway will lead — whether reconciliation is merely based on “forgive and forget”, “rehabilitation”, “truth revelation” or the involvement of a judicial process.

If judicial methods are used, “I’m afraid we will enter the wrong chamber”, said Agus Widjojo, a co-founder of National Leaders’ Children’s Forum (FSAB), a forum of children of leaders during past conflicts (his father was the slain General Sutoyo). “If you haven’t made peace with your past you cannot enter reconciliation yet.”

However, Kamala Chandrakirana, a member of the Coalition of Justice and the Disclosure of Truth (KKPK) and a former chairperson of the National Commission on Violence against Women, said reconciliation would be the end result of the prior steps, including revelation of the truth and rehabilitation of survivors and the dead victims.

Peaceful conflict settlement, say experienced mediators, requires recognition of mutual suffering. Last week both sides had started to listen to each other.

Nearing the closing of the event, amid booing from the audience, the poet Taufiq Ismail who was among the writers formerly harassed by the PKI’s Lekra cultural body launched into verses about questions from his grandchildren:

“There is said to be a party/That has slain 120 million people for 74 years in 75 lands/Every day they slaughtered 4,500/Datuk (Grandfather), how come people are so vicious?/They imposed forced labor/Their own people collapsed and died […]”

An elderly participant, Sayuto, described his own experience of detention without trial and forced labor in Serang, Banten, where they were forced to build schools and roads. As they were not fed, his friend said, “It must have been a deliberate decision to let us die.”

But Sayuto said residents had fed them while the local military watched. “People would say, come, eat here; they knew we were innocent.”

–]]>