AsiaPacificReport.nz

The Arctic 30’s thank you message after their release in November 2013 – cited in Peter Willcox’s new book out next week. Video: Greenpeace

By David Robie

When Anote Tong, former president of Kiribati, a collection of 33 tiny atolls sprawling across the Pacific equator in the frontline of climate change, believed he wasn’t being listened to, he thought of a simple strategy – polar bears.

By comparing himself and his country’s meagre population of 102,000 to the endangered creature, he suddenly got more headlines.

And he got the idea after having just seen a polar bear in the wild.

“I drew a comparison that what happens to polar bears will also be happening to us in our part of the world,” he explained.

Tong feared that the bears in their Arctic habitat, like the people of Kiribati in the Pacific, were in danger of losing their homes in the near future.

Today the polar bear is the mojo adopted by Greenpeace skipper Peter Willcox on his Facebook page.

The adventurous lifetime mariner and dedicated sailor was captain of the original Rainbow Warrior on her visit to Kiribati in 1985 en route from Rongelap atoll – where the crew evacuated an entire community whose health and wellbeing had been compromised by US nuclear tests in the 1950s – to Auckland where the ship was bombed by French secret agents in a madcap sabotage operation.

Russian bear

Willcox is well known in this part of the world as the relatively young skipper at the time of the sinking of his beloved ship at Marsden Wharf, but it is the Russian bear rather than its Arctic cousin that dominates his adventures while trying to save our planet.

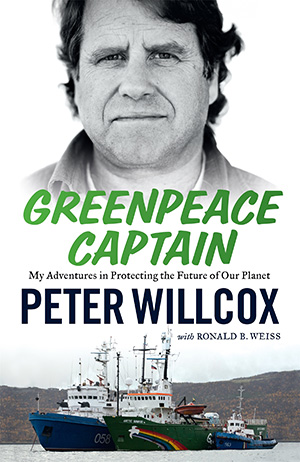

Six chapters of his new book, Greenpeace Captain: My Adventures in Protecting the Future of our Planet due for release next week, deal with Russian or Soviet security forces and hatchet men.

Six chapters of his new book, Greenpeace Captain: My Adventures in Protecting the Future of our Planet due for release next week, deal with Russian or Soviet security forces and hatchet men.

For the only captain to have skippered all three Rainbow Warriors over three decades of campaigning, the Arctic 30 arrest in 2013 – and the prospect of being imprisoned for up to 15 years for “piracy” – eclipsed the bombing shock 29 years earlier.

But his jailhouse diaries written in a clutch of bitterly cold prison cells in Murmansk and then Saint Petersburg to keep track of the saga – and his sanity – note several comparisons with his brush with French state terrorism in New Zealand.

The diaries helped keep up his spirits when facing the demoralising Kafkaesque intrigue of the Russian justice system and lack of communication with the outside world, especially his new wife of just six months at the time (he had been in prison for about a month before he was finally able to speak to Maggy who was valiantly crusading to get him set free).

Willcox had little idea of the enormous rallies and support that had spread out around the world seeking the release of him and his 29 crew and campaigners since their arrest and the seizure of their icebreaker ship Arctic Sunrise in September 2013.

Their “crime”. Attempting to scale the Gazprom “Goliath’s” Prirazlomnay oil rig in the Pechora Sea in the Arctic Circle. Willcox recalls:

“It’s an amazing feeling to realise that hundreds of ‘Free the Arctic 30’ protests demanding your release have taken place in dozens of countries around the world. Words cannot describe it, so I won’t try. The bottom line is that the international reaction makes me believe that what Greenpeace is doing is deeply appreciated and important.”

Among the supporters was folk singer and activist Pete Seeger – “We shall overcome” – a family friend who gave Willcox his first major deep-water sailing opportunity on board the Hudson River campaign sloop Clearwater.

Pete Seeger’s letter

Seeger penned a letter to President Putin at the age of 94 and then died a few weeks after Willcox was finally freed under a presidential amnesty and he had returned to his home in Maine.

“Dear, President Putin,” Seeger wrote, “I am one of the thousands now who believe you should let Captain Peter Willcox out of jail to explain why they climbed an offshore oil rig.

“Thank you very much for reading this letter. I’m sure you’ll make the right decision – the people of the world are watching.”

And Putin’s government finally did the right thing.

After the failure to pin any piracy case against Willcox and the crew – in spite of attempts to portray them as part of “an organised crime group” (i.e. Greenpeace) and that the Arctic 30 had “attacked the rig with weapons for our own personal gain”, the charge was downgraded to “hooliganism” – a vague category for any perceived enemy of the state.

The Willcox prison diaries make sobering reading – especially as he suffered from claustrophobia. Some brief highlights:

Wednesday, October 2:

“This was a bad day. The investigator met us on the ship. The first thing he did was point out that there was a bag of “drugs” in Katya’s backpack. Katya had picked a few wildflowers in Norway and was saving them to be dried and pressed … “

‘Scary charges’

Thursday, October 3:

“Half of us were dragged off to the investigator’s office today. We are now officially accused, not just suspected, and there was no reduction in the charges. The charges are quite humorous, or scary. They actually say we are not environmentalists but only pretending to be. How do they make this shit up?”

Wednesday, October 16:

“Today, I got my first phone call, but Maggy wasn’t home … I am afraid that my voice … broke at the end of the message…”

After a month, the investigators completely changed and it seemed to be back to square one.

Wednesday, October 23:

“One bit of very, very good news is the ‘marijuana’ in Dr Katya’s bag was dried flowers she was doing artwork with. I guess Hatchet-Face [the lead investigator] never saw pot before…”

Thursday, October 24:

“Red letter day, I guess. Maybe …Olysha [my translator] showed up: ‘You’re not a “pirate” any more …’ Turns out we are now ‘hooligans’ [like the Pussy Riot feminist punk collective]. The difference? Zero to seven years versus ten to 15 years.”

No wonder Willcox titled this chapter “One happy hooligan’.

Saturday, November 9:

“Spent the day (part of it) reading the Isleboro Island News [his wife’s newspaper with an editorial supporting Willcox]. I am so proud when I read ‘Maggy Willcox, editor’…”

November 2013:

The Arctic 30 were “sent to Kresty Prison – officially the ‘Investigative isolator Number One of the Administration of the Federal Service for the Execution of Punishments for the city of Saint Petersburg. Built in the late 1800s, it is the oldest prison in Europe and still the largest.”

Monday, November 18:

“I have now decided to take the heavenly observations of the last two days as a good sign. Not that I have always read the signs correctly. Note the rainbows in New Zealand in 1985 [just before the RW bombing] …”

Ordeal over

Finally, later that day after the judge read out a lengthy list of reasons why Willcox should be kept in jail, the indictment roll call reversed and in moments the ordeal was all over: “Bail is granted”.

They were all released after individual bail hearings.

Massive international publicity prompted Putin’s government to include the Arctic 30 in an amnesty bill passed to mark the 20th anniversary of the post-Cold War Russian constitution.

A fascinating and gripping yarn, which will be read avidly by many Greenpeace activists and campaigners globally over the years who are named by Willcox with many amusing and endearing anecdotes about the various struggles from a dawn raid in Peru to “something toxic in Denmark” to “Al-Qaeda, guns and diamonds” to icebreaking up the Amazon.

Willcox brings alive the many campaigns that he has been involved with and he isn’t coy about acknowledging the many mistakes along the way involved in Greenpeace’s particular brand of non-violent direct action.

I had the privilege of being with Willcox on the Rainbow Warrior for more than 10 weeks on the voyage from Hawai’i to Rongelap and the evacuation of the Rongelap community – which had an enormous lifelong impact on all of us on board – and then finally to Vanuatu and New Zealand.

His style of unflappable and committed leadership impressed me. We have crossed paths at various times since then as friends, notably around the 20th and 30th anniversary of the bombing.

Reading his opening chapter on the tragic death of photographer Fernando Pereira and demise of the first Rainbow Warrior and the fifth chapter on Rongelap were especially poignant moments for me.

I also noted that his sailboat back home in Maine is called Eyes of Fire, named after the Cree Indian wise woman often credited with the Rainbow Warrior legend – and also the title of my own book on that fated voyage.

Yet the breadth and range of all his adventures – and the crews serving with him – in the thick of almost every inspiring environmental challenge in the past three decades make gripping reading.

Would he give it up? No way. Climate change is now the greatest challenge of our generation, and Willcox wants to help make sure we get the future right – for his daughters, wife and our next generation.

In his most recent campaigns Captain Willcox and his crews have been tackling the plundering of Pacific tuna fish stocks and bearing witness to the Fukushima nuclear disaster legacy five years ago last month.

An amusing footnote to the book is a Peter Willcox final memo to President Putin. Read it to find out.

Greenpeace Captain: My Adventures in Protecting the Future of Our Planet, by Peter Willcox (Penguin Random House, Australia, release date, April 18).

–]]>