Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Alistair Sisson, Postdoctoral Research Associate, City Futures Research Centre, UNSW

Social and public housing is intensely stigmatised in Australia and has been for several decades. Estates in particular are often labelled “ghettos”, framed as places of danger, drugs and vice.

This stigma can lead to discrimination against tenants and can harm their sense of self-worth, as shown in Australia and around the world.

But it’s not just the Pauline Hansons of this world who are responsible for reinforcing stigma.

Stigma is the product of government policies. It also serves government policies, like privatisation and redevelopment. Until we recognise that, we’ll struggle to remove it.

The source of the stigma

Public housing is stigmatised in many different ways, as we discovered when reviewing a decade of policy documents and media coverage.

Read more: Melbourne tower lockdowns unfairly target already vulnerable public housing residents

Since the 1970s, public housing has gone through a process of residualisation due to the declining number of dwellings and the tightening of eligibility criteria. In other words, it has become home to more and more people who are marginalised and disadvantaged and portrayed as:

[…] a detached underclass unwilling or unable to engage with labour market opportunities or mainstream norms and values.

There is also a view that concentrating disadvantaged people in one area can worsen the problems they face. Common but contested ideas about concentrated disadvantage and neighbourhood effects can lead to the stigmatisation of whole estates or neighbourhoods.

Racism has also added to the stigma of some estates over the last 50 years, as access for Indigenous people has improved and as non-white migrants have been permitted to immigrate.

Decline and design

Public housing can sometimes stand out due to poor maintenance, particularly in gentrifying areas where private housing is new or renovated.

Brutalist towers in inner cities and back-to-front Radburn estates in outer suburbs can also contrast with their wider neighbourhoods.

These stereotypes stem from policies from the mid-1950s to the early 1970s that encouraged public tenants to buy their homes.

But residents who lived in apartments were excluded from such schemes, and cheaply built homes on the urban fringe were less attractive to buy. So these two types of estates became the dominant images of public housing, especially in Sydney and Melbourne.

These policies also reveal how public housing is viewed as inferior to home ownership. Home owners are portrayed as independent and good citizens, despite extensive government subsidies.

Read more: As coronavirus widens the renter-owner divide, housing policies will have to change

Stigma in action

The stigmatisation of public housing has been reflected in several recent government policies.

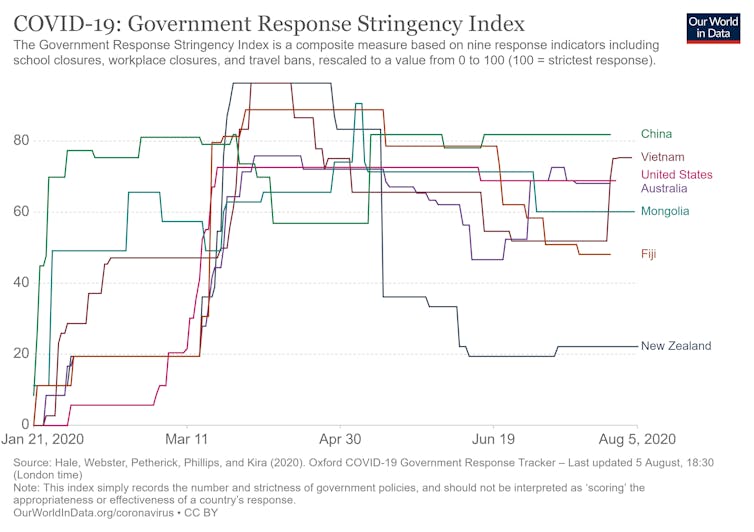

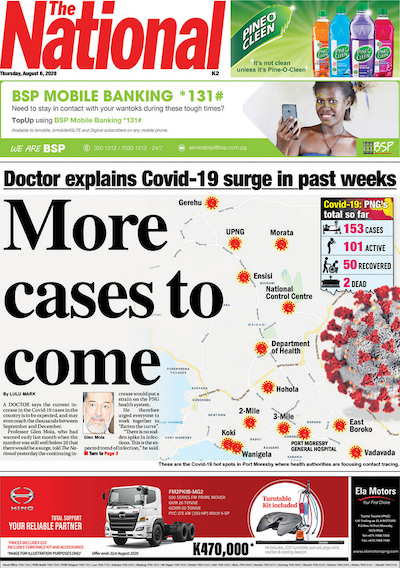

For example, the shared spaces and facilities of the high-rise public housing towers in Flemington and North Melbourne, in Victoria, were used as justifications for the hard lockdown during the coronavirus outbreak. The tenants were represented as an exceptional risk requiring an exceptional response.

Police deployed 500 officers to enforce a lockdown of unprecedented severity, while apartment residents in other hotspots had more freedoms and forewarning.

The relocation and privatisation of public housing in Millers Point, in Sydney, NSW, was another case of governments using stigma to justify policy.

Read more: Last of the Millers Point and Sirius tenants hang on as the money now pours in

The NSW government claimed residents received huge subsidies compared to other public housing tenants. It argued this money could be used to fund more housing in cheaper places.

But as the Tenants’ Union of NSW pointed out, these subsidies were made to seem larger than they were by including the difference between market rents and tenants’ rents. The subsidies weren’t paid to residents and didn’t reflect the cost of providing housing.

Yet The Daily Telegraph’s Miranda Devine argued tenants living in higher-value areas were responsible for the long waiting list for public housing.

This misrepresents the huge magnitude of public housing shortages and distracts from chronic under-funding.

The break-up of public housing

Stigma has also been used to justify estate renewal. The demolition and redevelopment of estates like Waterloo in Sydney and Carlton in Melbourne, along with many others around the world, has been justified by the argument that tenants’ disadvantage can result from the cultures or environments of estates.

Breaking them up is presented as a solution to disadvantage and anti-social behaviour.

These arguments divert attention away from government failures in reducing poverty. They also mask the economic and financial objectives of redevelopment, which research suggests are the primary drivers.

Meanwhile, the harm to tenants is dismissed as a cost worth paying for new or better housing.

Solutions to stigma

By shifting blame for various problems onto public housing tenants and estates, stigma reinforces the status quo of inadequate funding and thus poor maintenance, dwindling supply and cannibalisation through redevelopment and privatisation.

It also obscures the culpability of governments and the failure of markets to provide affordable housing, adequate incomes and social support.

Read more: As simple as finding a job? Getting people out of social housing is much more complex than that

To destigmatise public housing, fundamental changes in our housing system are needed. Better design, maintenance and stories are helpful, but can only do so much.

Part of the solution is to end the preferential treatment of home ownership and to treat different tenures equally through housing and tax policy. The security, stability, quality and profitability of your home should not depend on whether you own it or rent it from a private landlord or a social one.

This starts with upgrading public housing and building much more for the hundreds of thousands on waiting lists and the many more who are struggling in privately rented or mortgaged homes.

– ref. Why public housing is stigmatised and how we can fix it – https://theconversation.com/why-public-housing-is-stigmatised-and-how-we-can-fix-it-142913