SPECIAL REPORT – by Selwyn Manning.

On Tuesday, March 30, we lodged a series of questions to the Minister of Immigration Kris Faafoi, seeking answers to allegations that 10 Chinese workers, who were detained in custody pending deportation orders, were in fact victims of a human trafficking scam.

Throughout last week, the ten workers’ lawyer, Matt Robson, and union advocate Mike Treen of Unite Union, had been racing against the clock, seeking to halt deportation orders that Immigration New Zealand officials were advancing – seemingly with haste.

Two days later (April 1), two of the ten workers in fact received their deportation orders and were en-route to Auckland International Airport, escorted by Police.

Then, as the Police vehicle neared Auckland Airport on George Bolt Memorial Drive, one of the two, Ning Yu ‘escaped’!

How? The Chinese worker simply unbuckled his seatbelt, opened the Police car’s unlocked rear door, and ran away. Apparently, back in China, Ning Yu is a marathon runner.

While a number of Police units (including from the Police Dog Section, and Police helicopter) searched unsuccessfully for him, Ning Yu took refuge in a tree near a Golf Course on Nixon Road, Mangere. Then, once the Police helicopter flew off, he wandered about Mangere throughout the early hours of the morning.

After dawn rose on April 2, Ning Yu noticed a Chinese man jogging. As he passed, Ning Yu spoke to him in Mandarin. They had a conversation. Ning Yu told him his predicament. The jogger convinced him to hand himself in to Police. He agreed, and made his way to Auckland Central Police.

On arrival, Ning Yu told Police he absconded because he wanted to collect some money owned to him; “So he could take it home with him”. He was arrested, and later appeared before the Courts charged with escaping Police custody.

The charge sheet states: “At approximately 1952hrs on Friday the 1st of April 2021, Police were dispatched by the Northern Communication centre to assist NZ Immigration in escorting two deportees to the Auckland Airport as their flight was scheduled to depart from Auckland to China later in the evening.

“Police arrived at the Mount Eden Correction facility and received into their custody Ning YU, the Defendant in this matter.

“Due to the demeanour and background of the Defendant, he was not handcuffed. The Defendant was seated at the back of the Police Vehicle.

“On the way to the Airport, as the vehicle approached Cyril Kay Road on George Bolt Memorial Drive, the Defendant opened the petrol [sic] vehicle door and escaped,” The charge sheet stated.

On Saturday April 3, Ning Yu appeared before the Courts in Auckland. While there, the Police charge of absconding was withdrawn. He was returned to Police custody pending renewed deportation orders.

***

At this juncture, it is worth checking this worker’s allegations.

Throughout the ordeal (since Immigration investigators identified Ning Yu and the other nine as illegal workers) Ning Yu’s position was simple. He insisted he wanted to stay in New Zealand to work and earn some money. The wages he earned, he intended to send home to China for his wife and child. Ning Yu believed he was owed wages by an employer in Auckland, and that he had not earned enough, yet, to cover the USD$20,000 he states he paid an individual in China – who had initially arranged to expedite his Visa application to enter New Zealand. Back then, after paying the agent, Ning Yu said it took two days for his Visa to be allocated to him.

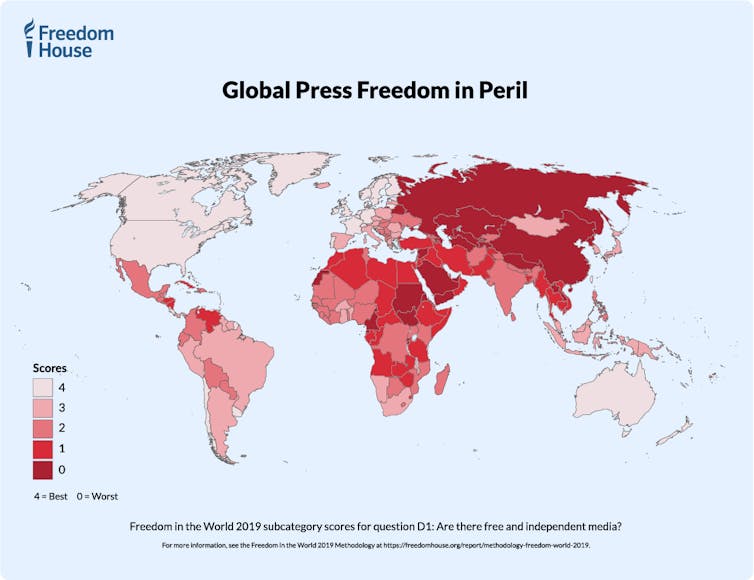

If true, this suggests corruption. Remember New Zealand is regarded as the least corrupt country in the world, equal to Denmark. If agents are demanding money from hopeful foreign workers, securing entry visas within days, and on arrival at Auckland Airport, these people are scooted off to work for employers as black labour – then that situation questions the corruption-free status New Zealand enjoys. And that, is clearly a public and national interest issue.

The seriousness of these allegations also draw forward concerns that New Zealand Government’s practice of out-sourcing Immigration New Zealand visa applications to agencies inside China, may have been corrupted.

Such concerns, in a democracy such as New Zealand, demand an expectation of thorough and transparent investigation. This case however, draws forward examples of bureaucratic control, silence, and an obvious ministerial convention being observed that prevents open and accountable oversight.

Far from answering allegations of serious crimes, questions remain unanswered.

Questions such as these:

- Who is the individual (the agent) that received approximately USD$20k from Ning Yu, the agent who allegedly managed, in two days, to acquire a Visa for this person to enter New Zealand?

- Who was the initial ‘employer’ that received Ning Yu and the other nine workers, and put them to work illegally in Auckland?

- Why were there no employment records held for Ning Yu and the nine other Chinese workers?

- Why were there no IRD numbers? No tax records?

- How many dodgy employers were Ning Yu (and the nine other workers) handed over to, to be exploited, paid under the table, under the minimum wage, without holiday pay, without health and safety protection, without the rights that a legitimate working visa demands?

- Why were New Zealand Government employment and labour inspectors prevented by Immigration New Zealand, and the Ministry of Business Innovation and Enterprise (MBIE), from interviewing the ten Chinese workers about their situation?

- Does this bureaucratic refusal-to-interview prevent an investigation from taking place into allegations of human trafficking and illegal employment by New Zealand-based companies and contractors?

- Do not the ten workers come under the protection of New Zealand Government’s Migrant Exploitation Policy?

- What is the definition of human trafficking that applies to victims of this type of crime in New Zealand?

On that last question, the United Nations defines human trafficking as the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of a person by deceptive, coercive or other improper means for the purpose of exploiting that person.

The United Nations definition appears relevant to the allegations in this case.

Despite the concerns as noted above, the Ministry of Business Innovation and Enterprise (MBIE)’s ‘Delegated Decision Maker’ replied to the Chinese workers’ lawyer, Matt Robson, on Thursday April 1 stating:

“Under the immigration delegations, the delegated decision makers have the authority to make certain ministerial intervention decisions on behalf of the Associate Minister of Immigration. I have carefully considered your representations. I advise I am not prepared to intervene in this case. As section 11 of the Immigration Act 2009 applies, I am not obliged to give reasons for my decision. Your clients will be deported from New Zealand at the discretion of Immigration New Zealand.”

***

Back to Thursday April 1, Minister of Immigration Kris Faafoi’s office continued to resist answering specific questions, electing rather to issue this statement:

‘Investigations are continuing and the Minister does not consider it appropriate to comment further than the statement he has provided to other media requests, which is:

“Ministers do not get involved in enforcement. That is an operational matter.

“We have been assured that the appropriate processes have been followed and Immigration NZ has not found any evidence of trafficking.

“Agencies are satisfied further investigations around employment and immigration breaches can be carried out without the need for the men to remain in New Zealand.

“As investigations are continuing, and this is an operational matter, it would not be appropriate to comment further.”’

The questions that were put to Minister Faafoi, prior to Ning Yu escaping from Police custody included:

Should New Zealand Police be heading an investigation into alleged human trafficking?

12: If so, has NZ Police been approached by you as Minister of Immigration or by your office or by Immigration New Zealand? And, is an investigation underway by New Zealand Police on this element of this issue?

The lawyer acting for the ten workers found there were:

a: No written employment agreements;

b: No wage and time records;

c: No paid holidays;

d: No legal wages;

e: No training in health and safety measures on construction sites.

13: Do you accept that the above points (a – e) are an accurate assessment of the ten workers situation? If not, why not? If so, does this suggest that they fall within the considerations of the Migrant Exploitation Policy? And if so, as suspected exploited foreign workers, do they have the right to seek recourse via New Zealand’s judicial process, and does this recourse halt deportation proceedings from occurring?

Regarding answers to these questions, the silence from the Beehive prevailed.

For the record, through their lawyer, Matt Robson (a former minister in the Labour-Alliance coalition government) and union representative Mike Treen (of Unite Union), the ten workers allege they:

- Were recruited by agents in China to go to New Zealand to work

- Paid the agents between USD$15,000 – $30,000

- Received their Visas within two to six days of applying

- Were met by agents (on arrival) at Auckland Airport

- Were taken to prearranged accommodation in Auckland

- Worked for various ‘employers’ at building sites around Auckland

- Never had employment contracts, wage or time records, or paid tax

- Were paid in cash

- Were put to work by the employers without work visas.

In a letter to Minister Faafoi dated April 1, 2021, Robson and Treen asserted that the above allegations demanded a robust investigation – that this situation meets the New Zealand Government’s Migrant Exploitation Policy, and, as such, the ten workers are witnesses to an alleged breach of New Zealand’s immigration and employment laws, and also human trafficking crimes.

They questioned why the Minister Kris Faafoi (who is also Minister of Justice) was determined to be satisfied with Immigration NZ officials who insisted to deport the workers with haste.

Minister Faafoi’s response, as noted above is, that it is an operational matter and that he is satisfied that Immigration has investigated the situation, including the allegations, and found no substance to them. The Minister was also satisfied that New Zealand’s employment and labour agencies can continue to investigate allegations of employment law breaches even after the ten workers have been deported back to China.

Also, for the record, the ten Chinese workers were scheduled for deportation on five flights to China leaving New Zealand between April 1st to 15th, 2021.

CONCLUSION:

The New Zealand public seldom has an appetite for bureaucracy. It is especially intolerant of government officials operating behind a shroud when issues of public and national interest are in question.

In reviewing this case it is clear, the allegations underlying this case demand an open and transparent investigation be held – even if that investigation should unearth cases of corruption and human trafficking – victims of exploitation between the People’s Republic of China and New Zealand. To avoid public scrutiny to the satisfaction of a reasonable standard, well, that is a national disgrace.

***

Ref. Questions from Selwyn Manning to Minister of Immigration Kris Faafoi, dated Tuesday, March 30, 2021.

For an article/editorial for EveningReport.nz (an associate member of the New Zealand Media Council) and syndicated outlets, I request the Minister of Immigration, Kris Faafoi, answer the following questions regarding the ten Chinese nationals detained (nine in Mt Eden Corrections Facility and one in Police custody) pending deportation proceedings. Thanks in advance for your considerations:

Regarding Employment Status (I ask this as it appears this has relevance in determining whether the ten fall under Migrant Exploitation Policy as exploited individuals):

1: Did the 10 workers (as individuals) have employment contracts while working in New Zealand?

2: Did their employer calculate tax PAYE deductions from their gross pay and pay Inland Revenue Department for money earned in New Zealand?

3: Did their employers calculate the cost of labour on their respective company accounts?

4: If not, is this a breach of New Zealand employment law and should this be investigated? If it should be investigated, what agency should conduct this investigation?

5: Do you believe under the currently known circumstances, that Mt Eden Corrections Facility is an appropriate place for the ten to reside pending the outcome of any inquiries?

6: On the facts so far, do you feel the 10 workers have potentially been exploited?

7: If you do not feel they have been exploited, why do you feel this is so?

8: If you do feel they have potentially been exploited, who or what do you feel is culpable? And, do you accept that they ten workers are key witnesses in an alleged human trafficking ring?

The lawyer representing the ten workers, the Honourable Matt Robson, said on Radio New Zealand’s Checkpoint programme (March 30, 2021) that he believed the ten workers are victims of exploitation by a human trafficking ring.

9: Do you believe this element has been satisfactorily investigated, and if so why?

10: If not, what should happen now?

11: Should New Zealand Police be heading an investigation into alleged human trafficking?

12: If so, has NZ Police been approached by you as Minister of Immigration or by your office or by Immigration New Zealand? And, is an investigation underway by New Zealand Police on this element of this issue?

The lawyer acting for the ten workers found there were:

a: No written employment agreements;

b: No wage and time records;

c: No paid holidays;

d: No legal wages;

e: No training in health and safety measures on construction sites.

13: Do you accept that the above points (a – e) are an accurate assessment of the ten workers situation? If not, why not? If so, does this suggest that they fall within the considerations of the Migrant Exploitation Policy? And if so, as suspected exploited foreign workers, do they have the right to seek recourse via New Zealand’s judicial process, and does this recourse halt deportation proceedings from occurring?

14: Has the Minister of Foreign Affairs been alerted (corresponded with) to this issue by your office, if so, what was the nature of that correspondence?

Thank you for your attention to the above questions. Your consideration is appreciated, and I request, that due the urgency relating to the situation and potential deportation of the ten workers, that your answers be given a priority.