Laura Iesue

From Miami, Florida

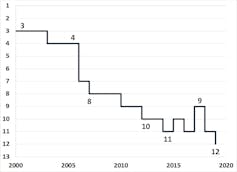

On March 29, 2020, Guatemala’s President Giammattei implemented an eight-day, country-wide curfew to stop the spread of COVID-19.[1] Ultimately, this lockdown would continue until October 1, 2020, as the virus continued to travel across communities.[2] While the viral spread continued to hold the public’s attention, media outlets slowly but increasingly began to report a rise in domestic violence incidents across Guatemala.[3][4] Statistically speaking, during the lockdown Guatemala saw an increase in cases of domestic violence reporting from 30 to 55 cases daily, according to the Women’s Secretariat of the Public Ministry[5]. In addition, there have also been an average of two murders of women and 5 to 6 rapes daily.[6] This jump in domestic violence echoes findings of organizations worldwide that reported an increase in women seeking domestic violence help compared to the previous year. [7][8][9][10] For instance, in Peru, over 1,200 women disappeared between March 11 and June 30, 2020.[11] Brazil reported a 22 percent increase in femicide in 2020 compared to 2019. [12] While domestic violence cases continue to make headlines, the uptick in domestic violence during COVID-19 stresses the importance to consider the relationship between criminal justice actors and Guatemalan society. Moreover, the question remains: what can we do to help domestic violence victims or prevent future violence?

Domestic Violence and Criminal Justice in Guatemalan Society

Domestic violence, particularly towards women, is an endemic problem and, in some instances, a culturally acceptable phenomenon. A 2015 Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) survey found that Guatemalans were more accepting of domestic violence, particularly gender-based domestic violence, than other Latin American countries, with 58 percent agreeing that suspected infidelity justified physical abuse.[13]Previous conservative estimates suggest that 24.5 percent of married women between the ages of 15-49 experience abuse.[14] While this begs the question as to why criminal justice actors are not doing more to address these issues in Guatemala, in many locales, Guatemalan law enforcement institutions continue to be under-funded, inaccessible to some, and are often inadequately trained to handle such chases. Abuse has also resulted in an average of two women per day being murdered in Guatemala.[15] These issues are compounded by the fact that simply some Guatemalan officers continue to uphold and believe in the societal and cultural norms that see domestic violence as acceptable or at the very least a family-related issue, that must be dealt with privately. Such discriminatory attitudes towards domestic violence victims means that police fail to respond promptly to reports, intervene in violent situations, open investigations when a woman is reported missing, or adequately follow-up on complaints. Ultimately this results in an organizational culture that hinders domestic violence reforms. In return, Guatemalans tend to distrust their police, which they view as ineffective and corrupt, and results in individuals choosing to opt out of reporting crimes .[16]

This is not to negate the reforms that have been made to criminalize acts of domestic violence and raise awareness about the issue. The most notable reform has been the creation of specialized courts for cases of alleged femicide and sexual, physical, and psychological violence. These courts have been influential in punishing offenders and providing the legal and psychological support needed for victims. Criminal justice reforms have also expanded to create specialized policing units solely responsible for handling allegations of domestic violence, called the Victims’ Services Department, part of Guatemala’s National Police (PNC). This specialized unit has 53 offices across Guatemala located within police headquarters. Specially trained officers assigned to this unit facilitate access to restorative justice for victims of domestic violence, violence against women, sexual violence, violence against children, and violence against the elderly. In addition to traditional police duties, these units provide emotional, physical, family, social, and legal assistance directly or in partnership with other organizations. The new laws and the establishment of the Victims’ Services Department are a step in the right direction. But there is still much that policymakers, human rights advocates, criminal justice practitioners, and civil society more broadly can do to ensure better support and access for victims. The Guatemalan police need more resources and training to help introduce programs to support domestic violence victims, which will allow them to gain legitimacy and earn the trust of the public. Moreover, past partnerships particularly with the United States which has helped aid officers through resources as well as training can make future reforms more likely. These partnerships, previously slashed under the Trump administration are key to the Biden administration’s strategy to deal with ongoing violence in Central America. [17][18]

If the Framework is There, What Are Some Short-Term Opportunities for Support?

Previous, small reforms of the criminal justice system to provide domestic violence outreach are promising and have set the framework for future endeavors. Guatemala can expand support into communities to provide outreach, support, and educational services through the collaboration of nonprofit organizations.[19]NGOs can also help increase awareness of the negative impacts of domestic violence on victims and lay the foundation for changes to cultural norms by educating young men.[20] Since domestic violence is just as much a public health issue as a criminal justice issue, the Guatemalan police, particularly in areas that emphasize community-based or model policing strategies, can help deliver the necessary services by tapping into the resources of local organizations to meet their safety and health objectives. This switch from traditional tough on crime or mano dura approaches to community-policing to deal with domestic violence, can foster more police legitimacy and trust, provided cases are handled with compassion and in cooperation with local organizations.

As an example of how police may foster outreach services is Honduras’s Model Police Precinct named “Bolsas Comunitarias.”[21] Under this program, groceries and essential staples were delivered to economically vulnerable and high risk communities.by the police, while also inviting individuals to contact them if there were any domestic violence concerns. Preliminary results from this study in Honduras found that over 20% of respondents followed up via text or phone to talk about their experience with the program. Over 50 percent reported that this service significantly impacted their overall well-being, as their situation was bad or very bad. As economic strain and living in an at-risk environment are statistically associated with domestic violence cases, there is potential for programs like “Bolsas Comunitarias” to be implemented in parts of Guatemala, ultimately alleviating some of the stressors associated with domestic violence. Similar services have popped up across Guatemala, but a strategic, country-wide implementation might have more impact and ensure that resources are provided to areas that need them the most.

Guatemalan sectors can also pull from policies being implemented elsewhere. Recently, United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres highlighted the need for countries to prioritize support for victims of domestic violence and suggested setting up emergency warning systems for people exposed to this violence.[22] Governments have taken steps to answer this call and have implemented some short-term solutions to help victims. For instance, in France, pharmacies and grocery stores are now providing warning systems to allow people to indicate if they are in danger or need assistance.[23] This includes the introduction of code words to alert staff that they need help.[24] Where technology is more accessible, remote or online services can also provide victims with health or counseling services.[25]

What about the Long-Term?

The COVID-19 crisis has revealed the need for more long-term domestic violence reform goals. This includes criminal justice and, more specifically, policing reforms from the top down. First, Guatemalan officials should institutionalize personnel training, as many police officers still lack training on how to handle and even spot domestic violence. Recent movements to recruit more female police officers are a step in the right direction. Still, more work needs to be done in reforming institutional, procedural, and monitoring policies on domestic violence.

Guatemala’s criminal justice system needs to ensure that its law enforcement and judicial systems continue to investigate and prosecute abusers. Also, more empirical work on just how many domestic violence cases are not prosecuted needs to be analyzed. This is especially important because it would provide more concrete data to criminal justice practitioners regarding where they are succeeding and where they are failing in the prosecution of domestic violence . Moreover, addressing these problems can send the message to would-be offenders and victims that domestic violence is not acceptable. Victims could come to trust the police and the criminal justice system to hold their abusers accountable.

Finally, police can continue to work within communities and local organizations to ensure equitable access to resources, legal assistance to victims, and community education about the harm caused by domestic violence. Such a multi-pronged approach not only enhances access to services and helps hold offenders accountable, but it can also be useful when ex-offenders re-enter society. Organizations can have interventions in place to prevent recidivism and work to breakdown the community norms resulting in acceptance of domestic violence. Ultimately, while we continue to assess the ramifications of COVID-19 on social institutions and consider how stressors due to the pandemic are increasing the incidence of domestic violence, this crisis can serve as a catalyst for meaningful institutional reform of the police and better outcomes for victims and improved police-community relations. The question remains whether Guatemala will collaborate with stakeholders to take advantage of this opportunity.

Laura Iesue is a PhD candidate and public criminologist at the University of Miami’s department of Sociology. Her work focuses on how crime policies and political attitudes on crime and violence are transferred from the Global North to the Global South and how this impacts local politics, communities and individuals. Her work particularly considers the impacts policies have on migration, crime types such as domestic violence, and even violence against journalists.

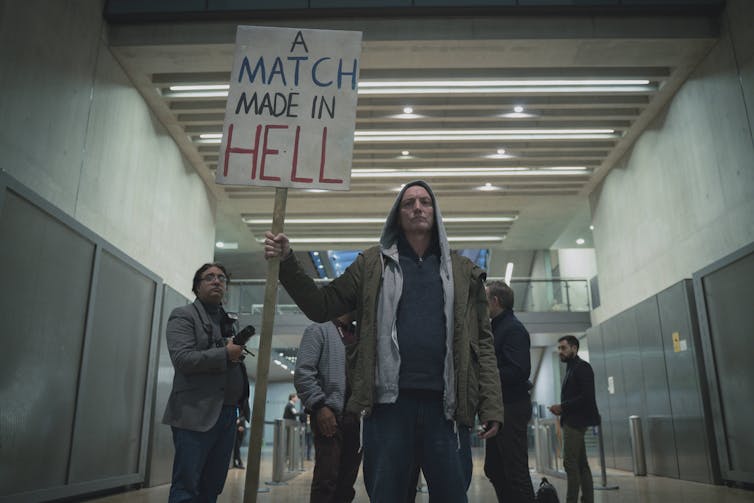

[Credit photo: common license]

Sources

[1]Tico Times, “Guatemala Rules out New Covid-19 Closures in Effort to Protect Economy,” Tico Times, 2020, http://ticotimes.net/2020/10/09/guatemala-rules-out-new-covid-19-closures-in-effort-to-protect-economy.

[2] Nestor Quixtan, “Guatemala Ends Lockdown (State of Calamity) on October 1,” CentralAmerica.com, 20202, https://www.centralamerica.com/living/news/guatemala-ends-lockdown/.

[3]ChapinTVa, “Aumentan Los Casos de Violencia Contra La Mujer,” ChapinTV, 2020, https://www.chapintv.com/noticia/aumentan-los-casos-de-violencia-contra-la-mujer/.

[4] ChapinTVb, “21 Escenas de Violencia Contra La Mujer Procesadas Por El MP,” ChapinTV, 2020, https://www.chapintv.com/noticia/21-escenas-de-violencia-contra-la-mujer-procesadas-por-el-mp/.

[5] El Diario, “Guatemala registra 55 casos al dia de violencia intrafamiliar por la cuarentena,” El Diario, 2020. https://www.eldiario.es/sociedad/guatemala-registra-violencia-intrafamiliar-cuarentena_1_2256633.html

[6] El Diario, “Guatemala registra 55 casos al dia de violencia intrafamiliar por la cuarentena,” El Diario, 2020. https://www.eldiario.es/sociedad/guatemala-registra-violencia-intrafamiliar-cuarentena_1_2256633.html

[7]Riley Beggin, “Stay Home, Don’t Stay Safe. Domestic Violence Calls Up Amid Michigan Lock-Down,” The Bridge, 2020, https://www.bridgemi.com/children-families/stay-home-dont-stay-safe- domestic-violence-calls-amid-michigan-lockdown.

[8] Emma Graham-Harrison, Angela Giuffida, and Helena Smith, “Lockdowns Around the World Bring Rise in Domestic Violence,” The Guardian, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/ mar/28/lockdowns-world-rise-domestic-violence.

[9] Megha Mohan, “Coronavirus: I’m in Lockdown With My Abuser,” BBC News, 2020.

[10] Amanda Taub, “A New Covid-19 Crisis: Domestic Abuse Rises Worldwide,” The New York Times, 2020.

[11] Lynn Marie Stephen, “A Pandemic Within a Pandemic Across Latin America,” U.S. News, October 10, 2020, https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2020-08-24/violence-against-latin-american-women-increases-during-pandemic.

[12] Stephen, “A Pandemic Within a Pandemic Across Latin America.”

[13] Dinorah Azpuru, “AmericasBarometer Insights: 2015; No: 123; Approval of Violence towards Women and Children in Guatemala,” 2015.

[14]Sarah Bott, Mary Goodwin, Alessandra Guedes, and Jennifer Adams Mendoza, “Violence against Women in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Comparative Analysis of Population-Based Data from 12 Countries” (Washington, DC, 2012), https://www1.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/violence-against-women-lac.pdf..

[15] Mahlet Atakilt Woldetsadik, “In Latin America, Breaking the Cycle of Intimate-Partner Abuse One Handwritten Letter at a Time,” Rand Blog: Pardee Initiative for Global Human Progress, 2015, https://www.rand.org/blog/2015/09/in-latin-america-breaking-the-cycle-of-intimate-partner.html.

[16] Perez, Orlando J. 2003. “Democratic Legitimacy and Public Insecurity: Crime and Democracy in El Salvador and Guatemala.” Political Science Quarterly 118(4): 627-644. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30035699

[17]Lesley Wroughton and Patricia Zengerle, “As Promised, Trump Slashes Aid to Central America over Migrants,” Reuters, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-immigration-trump/as-promised-trump-slashes-aid-to-central-america-over-migrants-idUSKCN1TI2C7.

[18] Elizabeth Malkin, “Trump Turns U.S. Policy in Central America on Its Head,” The New York Times, 2019.

[19] Bennett, Larry W., Stephanie Riger, Paul A. Schewe, April Howard, and Sharon M. Wasco. 2004. “Effectiveness of Hotline, Advocacy, Counseling, and Shelter Services for Victims of Domestic Violence: A Statewide Evaluation.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 19 (7): 815–29. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0886260504265687

[20] Cismaru, Magdalena, and Anne Marie Lavack. 2011. “Campaigns Targeting Perpetrators of Intimate Partner Violence.” Trauma, Violence, and Abuse 12 (4): 183–97. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ 10.1177/1524838011416376. Accessed April 4, 2020.

[21] Similar projects were conducted in Guatemala, but to date the author does not know of any formal reports on their impacts. Brenda Larios, “PNC Entrega Mil 400 Bolsas de Víveres a Familias Damnificadas En Tactic,” AGN: Guatemalteca de noticias, 2020, https://agn.gt/pnc-entrega-mil-400-bolsas-de-viveres-a-familias-damnificadas-en-tactic/.

[22] Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, “Violence Against Women and Girls: The Shadow Pandemic,” UN Women, 2020,

https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2020/4/statement-ed-phumzile-violence- against-women-during-pandemic.(https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2020/4/statement-ed-phumzile-violence- against

women-during-pandemic).

[23] I Guenfound, “French Women Use Code Words at Pharmacies to Escape Domestic Violence during Coronavirus Lockdown.,” ABC News, 2020, https://abcnews.go.com/International/french-women-code-words-pharmacies-escape-domestic-violence/story?id=69954238.

[24] Sophie Davies and Emma Batha, “Europe Braces for Domestic Abuse ‘perfect Storm’ amid Coronavirus Lockdown,” Reuters, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-health-coronavirus-women-violence/europe-braces-for-domestic-abuse-perfect-storm-amid-coronavirus-lockdown-idUKKBN21D2WU.

[25] Susan Mattson, Nelma Shearer, and Carol O. Long, “Exploring Telehealth Opportunities in Domestic Violence Shelters,” Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practicioners 14, no. 10 (2002): 465–70.