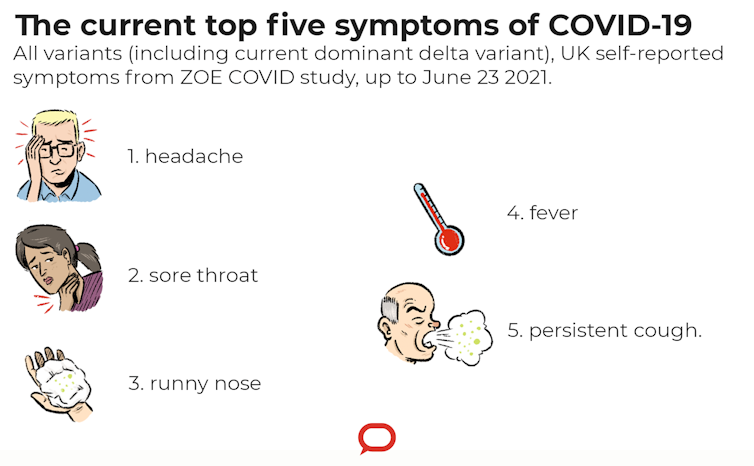

The World Health Organisation says the delta variant of covid-19 has been identified in 85 countries and is spreading rapidly in unvaccinated populations around the world. Indonesia registered a record 21,807 cases on Wednesday. Video: Al Jazeera

Asia Pacific Report newsdesk

Indonesia’s most populated and popular islands are bracing for emergency lockdown measures from this weekend, with President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo touting the inevitability of shifting policy amid soaring covid-19 cases, reports The Jakarta Post.

The country recorded another record-breaking day with 21,807 new covid-19 cases and 467 deaths in a day, according to official figures published on Wednesday.

That brings the country’s overall caseload to 2,178,272 and deaths to 58,491 – a toll among the highest in Asia.

The numbers are widely regarded as conservative estimates because of severely inadequate testing outside Jakarta.

The Health Ministry also reported alarming bed occupancy rates (BORs) in Jakarta, Banten and West Java – all of which have surpassed 90 percent – followed by Yogyakarta and Central Java at 89 and 87 percent, respectively.

President Widodo said the restrictions would begin tomorrow — Saturday — and last until July 20 on the most populous island of Java and the tourist island of Bali, reports Al Jazeera.

In a televised address yesterday, Widodo said: “This situation requires us to take more decisive steps so that we can together stem the spread of covid-19.”

Worst-hit nation

The details of the measures were being announced later, he added.

Indonesia is Southeast Asia’s worst-hit nation with new cases topping 21,000 every day. The surge has overwhelmed hospitals and resulted in a shortage of oxygen in the capital, Jakarta.

A government document said the new restrictions aim to cut daily cases to below 10,000, and will include work-at-home orders for all non-essential sectors and the continued closure of schools and universities.

The document also said public amenities like beaches, parks, tourist attractions and places of worship must close, while restaurants can offer only take away or delivery services.

Constructions sites can continue operating as normal, however.

Udayana University Professor Gusti Ngurah Mahardika, a virologist on the island of Bali where the number of daily confirmed cases have more than quadrupled in two weeks, said the proposed restrictions were not enough.

“I have seen the new emergency measure but I am sceptical. We need a lockdown but the problem is there is just no money to keep people at home,” he said.

Infection rate far higher

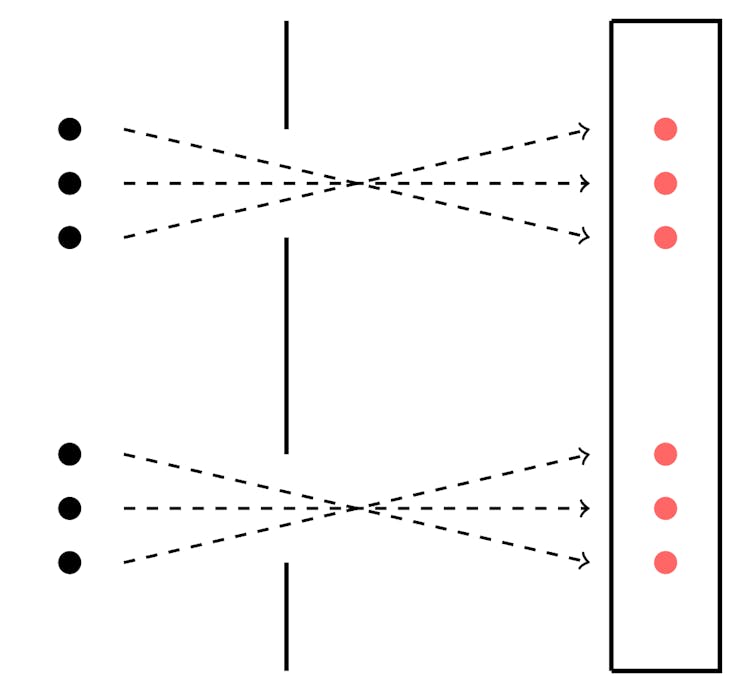

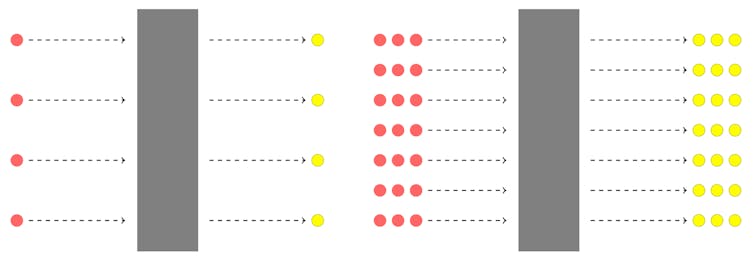

Infectious disease experts say modelling suggested Indonesia’s true daily infection rate was at least 10 times higher than the official count.

“The problem in Indonesia is that testing rates are very low because only people who present themselves at hospitals with symptoms receive free tests. Everyone else has to pay,” said Dr Dicky Budiman, an epidemiologist who has helped formulate the Indonesian Ministry of Health’s pandemic management strategy for 20 years.

“Based on the current reproduction rate in Indonesia that has climbed from 1.19 in January to 1.4 in June, I estimated there at least 200,000 new cases in the country today.

“But if I compare that with modelling by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation in Seattle, it is much higher, about 350,000 new infections per day. That’s as high as India before the peak.”

A virologist in Java advising the Ministry of Health, who spoke to reporters on condition of anonymity because they were not authorised to speak to the media, said the virus spread so quickly because many Indonesians exhibiting symptoms of covid-19 prefer to stay home.

“When we see the hospitals full with patients it’s only the tip of the iceberg because only 10 to 15 percent of sick people in Indonesia go to hospitals,” the virologist said.

“The rest will stay at home and self-remedy because they prefer to stay with their family.

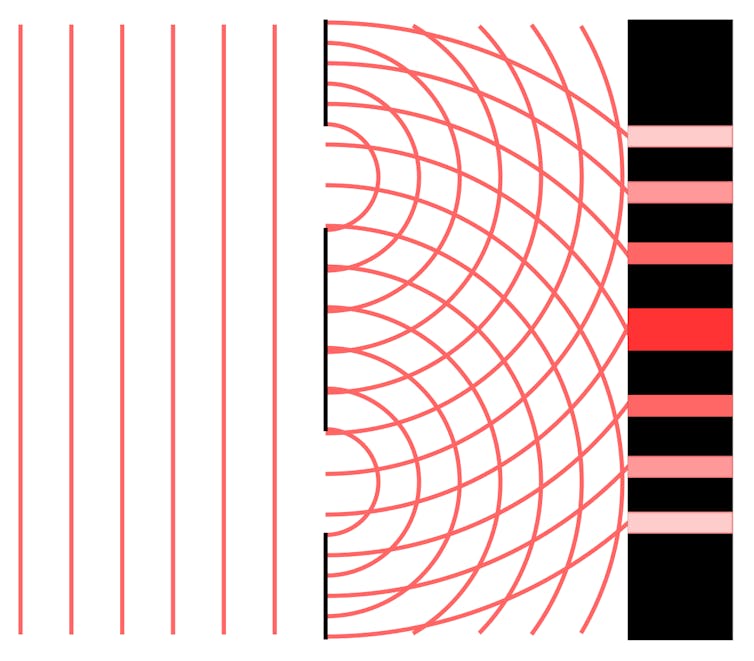

“This has happened since the start of the pandemic but with the delta variant now becoming dominant it’s a much more serious problem because the secondary infection rate in households for the delta variant is 100 percent.

“That means if one member of a household is infected, they all get infected. But as their symptoms become worse and people experience trouble breathing, we expect many more people will come to hospitals, like what we saw in India.”

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz