Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Peter McNeil, Distinguished Professor of Design History, UTS, University of Technology Sydney

NDZ/STAR MAX/IPx

Democratic congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has ignited both controversy and celebration after wearing a gown to the Met Gala emblazoned in red graffiti text with the statement “Tax the Rich”.

Appearing as a guest of the Metropolitan Museum of Art at the annual fund raiser, (for which tickets cost tens of thousand dollars), the left-wing politician wore a custom gown by fashion brand Brother Vellies, bringing with her the label’s founder, the young Black designer and activist Aurora James.

Using fashion as a tool to address wider social concerns has, in fact, long been a strategy for people seeking to make change — including wearing these clothes in spaces of influence.

From 19th century Suffragettes who pounded the streets in heels, ultra-feminine dress and large “picture” hats to refute claims that they were unwomanly, to patriot textiles in the second world war, to Indigenous Australian street clothes and accessories by a brand such as Dizzy Couture today, dress has historically conveyed political messages, creating “looks” for generations of change agents.

Here are 5 clothing acts as provocations that changed history.

1. George Washington’s suit

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

The founders of the American Revolution wished to break with the old codes of European aristocracy. Much of the world still had “sumptuary laws”: legal edicts that regulated the types, materials and amounts of cloth, colours, jewellery and accessories permitted to various social groups.

In North America, the formal clothing codes of the old regime were actively resisted: men were not expected to wear the expensive and colourful embroidered silks typically worn to European courts. Their imported fabrics were considered bad for local economies, and their elite air at odds with the idea that all men might now be (relatively) equal.

President elect George Washington was sculpted by Houdon in the late 18th century with a button missing from his waistcoat. This was a deliberate gesture to show his actions were more important than his appearance. He also wore plain, home-spun American woollen cloth for his inauguration instead of the expected silk or velvet. This was a firm demonstration of North American independence and perhaps the first American “business casual”.

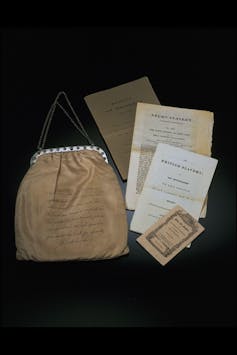

2. The Abolitionist handbag

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London, CC BY-NC

Since the late 18th century, a range of objects from jewellery to printed dishes were produced to critique the Slave Trade.

British Quakers had advocated for Abolition in 1783. The Female Society for Birmingham (originally the Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves, the first such group) mobilised their anti-slavery followers with handbags printed with images and slogans designed to gain support for the Abolitionist movement.

The silk drawstring bags, made by women in sewing circles, were presented to prominent figures such as George IV and Princess Victoria. The bags contained newspaper articles and tracts supportive of Abolition.

The Slavery Abolition Act, which provided for the immediate abolition of slavery in most of the British Empire was passed ten years later, in 1833. A similar Act was ratified in the USA only in 1865.

3. No feather hats

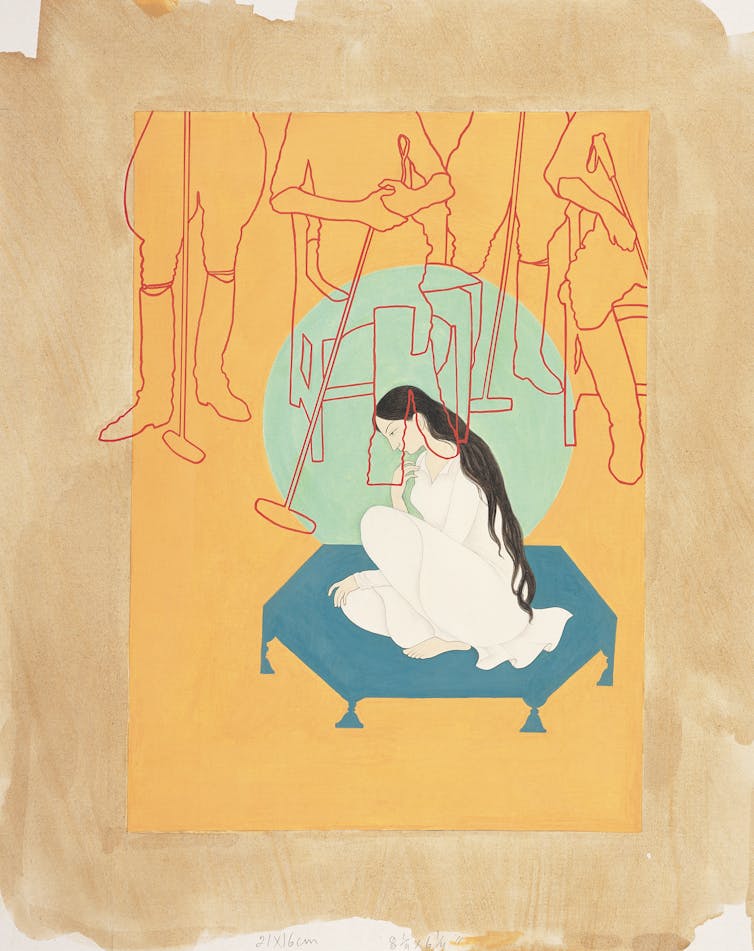

Te Papa, CC BY-NC-ND

The ostrich and exotic bird industry was massive in the 19th century: as well as plumes, women wore whole bodies of birds as accessories, such as hummingbird earrings.

The ostrich plume “double fluff” industry was centred on South Africa, where the feathers were worth more than gold. They were exported to rooms in London and New York where exhausted young girls finished and dyed them for retail.

In 1914 a massive “feather crash” saw the raw material become close to worthless. Young women interested in the growing national park and conservation movements objected to the trade on ecological grounds. They simply stopped wearing the fashion, starting a global “anti-plumage” movement.

The women involved with the Massachusetts Audubon Society were so successful that their lobbying led to the first US federal conservation legislation, The Lacey Act (1900). Taxidermied birds, feather boas and birds as earrings became largely unfashionable and were rarely seen again in women’s fashion.

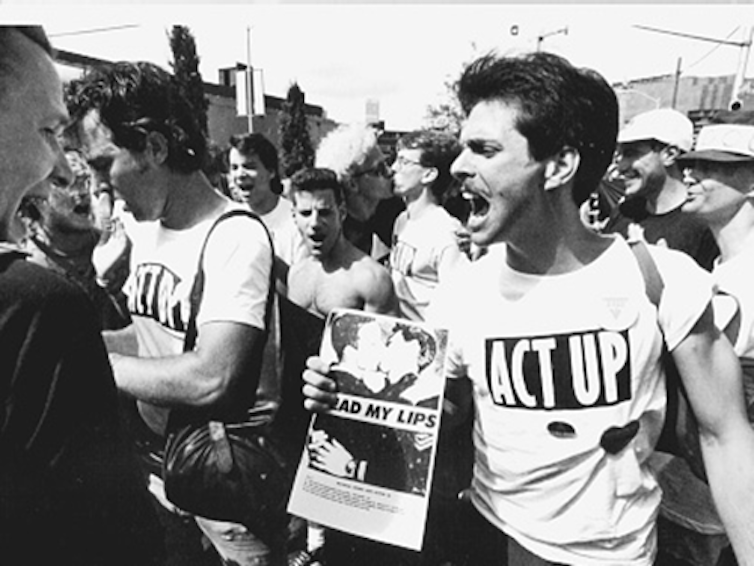

4. The ACT UP T-shirt

“Act Up Oral History Project”, CC BY-NC-SA

The AIDS crisis of the 1980s-90s saw the mobilisation of a unique blend of activism born from the women’s, Hispanic, Black power and 1970s gay movements. ACT UP New York determined that only anger and civil disobedience would focus the attention of government and big pharma on the plight of mainly gay men’s health.

A series of extraordinary “zaps” or site-specific protests, often theatrical, was engineered. ACT UP’s membership included skilled figures from advertising and design who created unified and stylish T-shirts, posters and banners. The designs were clean, slick and looked just like good advertising.

As Sarah Schulman recently demonstrated in her 20 year history of ACT UP, the bold T-shirt designs both created optimum impact for ACT UP’s protests on the TV news and a new pro-gay identity. Worn with Doc Marten shoes, leather jackets, clean and tight jeans or denim shorts, ACT UP established the look of gay urban men for a generation.

Government bodies and large drug companies were shamed by the public protests into adopting better and more rational health messaging, conducting better funded and more equitable drug trials and selling cheaper retrovirals.

5. When Katharine met Maggie

In 1984, designer Katharine Hamnett wore a t-shirt that read, “58% DONT WANT PERSHING” (a reference to nuclear missiles) to a high profile fashion evening attended by conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

Hamnett made her T-shirt the night before, recognising the opportunity she had, and hid it under her coat upon entry. Its graphic format owes a debt to both 1970s Punk and ACT UP. She later recalled of the widely photographed encounter with Thatcher:

She looked down and said, “You seem to be wearing a rather strong message on your T-shirt”, then she bent down to read it and let out a squawk, like a chicken.

Social change needs its visual forms. Fashion is one of them. Fashion is a brilliant communicator of new ideas. That we are reading about AOC’s clothing “controversy” shows she fully understands fashion’s power.

![]()

Peter McNeil does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Beyond AOC’s ‘Tax the Rich’ dress: 5 acts of fashion provocation that changed history – https://theconversation.com/beyond-aocs-tax-the-rich-dress-5-acts-of-fashion-provocation-that-changed-history-167974