ANALYSIS: By Yamin Kogoya

Two Melanesian state leaders addressed the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) on West Papua last week.

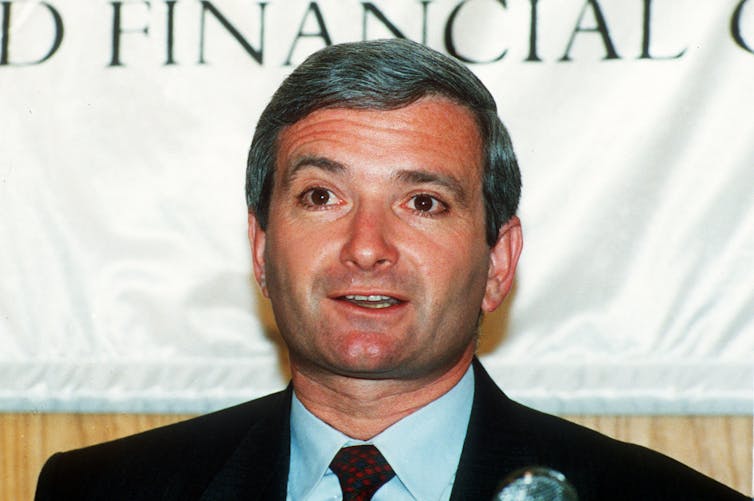

During the 76th UNGA, both Papua New Guinea’s Prime Minister, James Marape, and Vanuatu’s Prime Minister, Bob Loughman, expressed concern about human rights issues in West Papua.

While Marape devoted only 30 seconds of his 41-and-a-half-minute address to making some indirect remarks on West Papua, Loughman spent several minutes taking a more assertive approach.

Regardless, that 30 seconds was greatly appreciated by Papuans.

Here is the transcript of Loughman’s speech at the UNGA on 27 September 2021:

“In my region, New Caledonia, ‘French Polynesia’ and West Papua are still struggling for self-determination.

“Drawing attention to the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples as stipulated in the UN Charter, it is important that the UN and the international community continue to support the relevant territories giving them an equal opportunity to determine their own statehood.

“In my region, the indigenous people of West Papua continue to suffer from human rights violations.

“The Pacific Form and ACP leaders, among other leaders, have called on the Indonesian government to allow the United Nation’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to visit West Papua Province and to provide an independent assessment of the human rights situation.

“Today, there has been little progress on this plan. I hope the international community, through appropriate UN-led process, takes a serious look at this issue and addresses it fairly.”

Human rights concerns

The following is the transcript of the brief West Papua section in Marape’s address to the UNGA on 26 September 2021.

“While commenting on the United Nations peace effort on the PNG, I would also like to recall on the Pacific islands Leaders Forum (PIF) in 2019 and the out-sitting visit by the United Nations human rights mechanisms to address the alleged human rights concern in our regional neighbourhood.

“This visit is very important to ensure that the greater people have peace within their respective sovereignty and their rights and cultural dignity are fully preserved and maintained”.

The two leaders of Melanesian states expressed concern over West Papua in accordance with resolutions adopted by regional bodies, such as the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) and the African, Caribbean, and Pacific States (ACP) in 2019.

One of the most important features of these resolutions was the call for the root causes of the West Papua problem to be addressed.

These resolutions remain primarily concerned with human rights issues. In reality, these violations of human rights result from deeper problems that are often forgotten or ignored.

For Papuans, this deeper problem relates to sovereignty: the Papuans contend that the means by which Indonesia has claimed sovereignty over West Papua was fraudulent and immoral.

Tackling the root causes

Unless the world’s leaders and international institutions — the United Nations, the ACP and/or the PIF — address these root causes, it is highly unlikely that human rights problems will be solved.

In addition, continuing to acknowledge Indonesia’s sovereignty in these resolutions would legitimise human rights abuses, since these violations are a consequence of Indonesia’s breach of sovereignty.

During the 2016 UNGA, leaders of seven Pacific nations (Vanuatu, Palau, Tonga, Tuvalu, Marshall Islands, and the Solomon Islands) raised the issues of West Papua.

Many of them agreed that the root causes should be addressed. To date, we are no closer to having a conversation about these issues than we were a few years ago.

It appears that voices like those just heard from two leaders from Melanesia at the forum occur once in a blue moon and then vanish into a sea of deaf ears.

A new lens on Indonesian colonialism

The West Papua situation has since deteriorated. In West Papua, shootings continue unabated, and prominent leaders such as Victor Yeimo continue to be arrested and imprisoned.

We continue to receive reports of Papuan bodies being found in the gutter, on the street, in the bush, in hospitals, houses, and hotels. The internal world is also bombarded by images and videos that depict Papuans who have been tortured, abused, burned or killed.

Another young prominent Papuan leader, Abock Busup, died suddenly in a Jakarta hotel last Sunday.

Abock was the former regent of the Yahukimo, the Star Mountains Highlands in Papua, and the chairman of the Papua National Mandate Party’s regional leadership council.

In May, Papuans also lost the Vice-Governor of the Papuan Province, Klemen Tinal, at Abdi Waluyo Hospital in Jakarta.

In September 2020, another prominent Papuan leader from the highlands region of Papua, Lanny Jaya, Bertus Kogoya, died in a hotel room in Jakarta.

Kogoya was the chair of the Regional Leadership Council (DPW) of the Papua Provincial Working Party at the time of his death.

Jakarta dangerous for Papuans

Jakarta, the capital and most populous city of Indonesia, has been dangerous and unwelcoming for Papuans, who are punished with death upon arrival. The causes of their deaths are rarely determined by authorities.

In response to these never-ending brutalities, the West Papuan National Liberation Army (TPNPB), the armed wing of the resistance movement, retaliated. A number of deaths of security personnel and immigrants have been attributed to them.

The armed wing often claimed that their targeted victims are not ordinary immigrants, but people who have been either directly or indirectly implicated into the state’s security apparatus, which threaten Papuans throughout the land.

A military post in Sorong, in the Mybrat region of West Papua, was attacked in early September 2021, resulting in the death of four Indonesian soldiers.

Two years earlier, in December 2018, the TNPB killed at least 19 workers in the Nduga region, suspected to be members of security forces.

In recent weeks, a 22-year-old health worker, Gabriella Maelani, was killed in the Kiwirok district of Star Highlands. This, coupled with the burning of public health buildings, are only a few of the heartbreaking atrocities perpetrated in West Papua against humanity.

These shootings and killings have conflicting narratives wherein the West Papua liberation army accused their victims of being either directly or indirectly responsible for the deaths of Papuans.

Justifying ‘securitisation’

In contrast, the government of Indonesia has attributed all forms of violence to the liberation armed wing, which conveniently justifies their securitisation of the entire region.

A massive humanitarian crisis has resulted from these killings, displacing the residents of entire areas from their homes and forcing them into forests, causing further deaths of villagers, either through starvation, sickness, or reprisal attacks by the Indonesian military.

Human tragedies never end in the land popularly known as “the little heaven that falls to earth.”

As reported in Asia Pacific Report, lawyer and human rights activist Veronica Koman has called for an independent investigation into the death of the Kiwirok’s health workers.

But even such requests are consistently denied by the authorities. Human rights organisations, NGOs, and rights activists have pressed Jakarta to investigate these atrocities for years with no result to date.

In West Papua, people live in conditions of what French sociologist Émile Durkheim termed anomie, meaning the breakdown of the existential structure that holds human life, morality, ethics, norms, and values together.

In this world, what is justice for one is a crime against another. It is a complete breakdown of the system; it is a war of freedom and survival in a tangled world – entanglements which make it virtually impossible to investigate and prosecute those responsible for these crimes when the very system necessary to deliver justice is inherently incongruent.

That is what anomie is, in essence.

An exotic dream

West Papua may seem like an exotic dream world full of wealth and lush greenery to Indonesians and Western companies which thrive on its natural resources. These people have no concern for protecting this paradise world; instead, they go there to dig, cut, extract, and steal for their multimillion-dollar mansion in Jakarta, London, Washington, or Canberra.

This is the only place that Papuans call home on this planet. Tragically, this home has been turned into a theatre of killings.

The fate of their land and cultural identities are at stake as the colonial Indonesians and imperial West have thrust the Papuan people into a fierce struggle for survival in their ancestral homeland.

The deaths of Papuans, immigrants, and security personnel are not isolated incidents. They are the victims of big wars for global control fought behind the scenes in Rome, Beijing, Jakarta, London, Canberra, Moscow, Auckland, Washington, Tokyo, and Canberra.

The real perpetrators live in these imperial capital cities. The mourning relatives in West Papua or elsewhere in Indonesia will never meet these perpetrators nor see them brought to justice as they control the very system in which these crimes are perpetrated.

According to a report from the Asian Human Rights Commission in 2013 entitled “Neglected Genocide”, Australia provided Iroquois helicopters to Indonesia in the 1970s along with Bell UH-1H Huey helicopters from the United States.

These helicopters, among other aircraft and resources, were used by Indonesia to bomb Papua’s highland villages of Bolakme, Bokondini, Pyramid, Kelila, Tagime, and surrounding areas.

Australian-trained terror squad

Danny Kogoya, one of the key OPM commanders who died in hospital near the PNG-Indonesia border in 2013, was shot by an anti-terrorist squad trained by the Australian elites.

Kogoya died as a result of an infection caused by the amputation of his right leg after having been shot in Entrop Jayapura, Jayapura, Indonesia on 2 September 2012.

Maire Leadbeater, a New Zealand-based human rights activist, wrote an article published in Green-Left in May 2021 in which she stated: “Since 2008, New Zealand has exported military aircraft parts to the Indonesian Air Force.”

In most years, including 2020, these parts are listed as “P3 Orion, C130 Hercules & CASA Military Aircraft: Engines, Propellers & Components including Casa Hubs and Actuators”.

West Papua will see the use of this military hardware as Indonesia continues to increase its presence in the region in an attempt to crack down on the highlands, which have already suffered massive displacement in the Nduga region.

It is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of the immense volume of weaponry, skills, and training the Western governments supply to Indonesia.

It is important to ask why Western governments aid Indonesia in eliminating indigenous Papuans. These questions can be answered by looking at what the Māori of New Zealand, the Aboriginals of Australia, and the Native Americans endured.

Colonisation by settlement

Colonisation through settlement has proven to be the most pernicious in human history. Tragically, this project is being undertaken by Indonesians in West Papua with the assistance of Western governments, based on the logic of exterminating one population in order to replace it with another.

Europeans have done this in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States with great success.

Currently, they are dispensing all of their knowledge, expertise, and weapons to Indonesians in order to eradicate the Papuans. They continue to supply arms to Indonesia, despite knowing the arms will be used against the Papuans.

The Indonesian government’s execution of their plan to exterminate Papuans is neither secret nor new. In 1963, General Ali Moertopo declared that the Papuan people should be sent to the moon.

Decades later, General Luhut Panjaitan said the Papuans should be sent to the Pacific.

Recently, General Hendropriyono said the 2 million Papuans should be sent to Manado Island in Northern Sulawesi.

Indonesian generals’ voices

These words are coming from Indonesia’s military generals who undoubtedly have military affiliations with those Western countries that supply those munitions.

International organisations such as the UN, the PIF, and the ACP fail to challenge Western-backed Indonesia’s pernicious logic of annihilating the Papuan people through the system of “settler colonialism”.

Both West Papua and Papua are not simply provinces of Indonesia but Indonesian settler colonies.

Viewing West Papua through the lens of a Settler Colony helps to understand all the activities conducted in region better, as Indonesia attempt to assimilate, reduce, remove, and eliminate the original inhabitants so that new settlers can occupy the vacated lands.

Without real actions, written resolutions and human rights rhetoric at UN forums are nothing more than funeral letters or platitudes intended to comfort the dying and entertain the perpetrators.

The ultimate betrayal

Papuans’ stories are reminiscent of a Hollywood movie in which deserted civilians wait for a rescue train which never arrives. The sad truth is that Papuans die every day waiting for this train.

A train did arrive on 1 December 1961, when the Dutch prepared and assisted the Papuans in joining the new global community of the independent state.

Tragically, Papuans were thrown off the train when Indonesia invaded West Papua in 1963, after being permitted to invade by those imperial planners during the controversial New York Agreement a year earlier.

A sham referendum that followed in 1969 irrevocably sealed the fate of the Papuan people, known to Papuans as the “Act of No Choice”. To date, Papuans are still awaiting another train that will bring them into the global nationhood of humanity. The question is, who controls this train?

Despite all of these tragedies, the will to live continues to ignite the flames of hope and freedom in a world encircled by the clutches of despair.

Often, that will to live is strengthened each time West Papua is mentioned at the United Nations, which motivates the Papuans to wait for the next long-awaited train, which never arrives. Rumours and news spread, and their social media accounts are filled with messages of hope, thanksgiving, and prayers.

Appreciation messages

Here are the comments of these varieties expressed in appreciation for the speeches delivered by two Melanesian state leaders recently at the UNGA.

Free West Papua Camping Facebook Page wrote the following words:

“Our Sincere Gratitude and a big thank you to Prime minister of PNG, Hon. MP. Mr James Marape, to recall the PIF Leaders’ Resolution on West Papua in 2019, on your speech (mins. 41.05-41.35) at UNGA, September 25 2021. (41.05:) (41.35). Only God knows that the 30 seconds part of your speech is highly appreciated, respected and valued by our people back home who are struggling under Indonesian atrocities and colonial system and all Papuans in exile including those that are residing in your beloved country, PNG. May God bless your leadership and your government and your people back home to become a blessing for other countries, especially, for the Melanesians and the Pacific Islanders in our region. Peace be with you and your entire country.

Long live PNG??

Long live MSG countries!!

Long God yumi trustem and stanap for our freedom, dignity, justice, sovereignty, peace and cultural identities.

Freedom for West Papua, one pela day”

The campaign page also posted the following message in appreciation of the Prime Minister of Vanuatu’s speech:

“On behalf of the people of West Papua we thank you to Prime Minister of Vanuatu, Hon. MP Mr Bob Loughman, for Addresses [sic] Human Rights situations at United Nations today on his speech (at UNGA, September 25, 2021)

Long live Vanuatu, God bless VANUATU”

Papua’s fate hangs in “30 Seconds” and only God knows the outcome.

In Marape’s 41-and-a-half-minute speech, only 30 seconds were devoted to West Papua. In addition to omitting the name of West Papua, the speech was carefully constructed, avoiding certain words that may reveal the identities of those who commit heinous crimes that go unpunished.

Key message for families

Nevertheless, that 30-second speech was highly appreciated by the families of the victims.

The reality of the Papuans under Indonesian rule can be summarised in those 30 seconds.

As Papuans wait in the emergency room of an Indonesian hospital, they feel as if they are on life support as Indonesia continues to fiddle with its oxygen life support system. In that situation, time and rescue is of the essence.

Marape’s 30-second statement regarding West Papua prompted the Free West Papua Campaign to remind an unresponsive twin brother that time is running out.

In spite of it seeming inconsequential to him and the rest of the world, the Free West Papua Campaign says that “those 30 seconds are highly valued, appreciated and respected because every second counts to prevent another Papuan death accompanied by another loss of land.”

In the end, “only God knows the 30 seconds” declared the Free West Papua Campaign groups.

Both God and 30 seconds symbolised impossibilities of great magnitude and triviality, and a courageous human agent like James Marape can turn these impossibilities into possibilities to determine the fate of dying humanity and biodiversity in the land of Papua.

Yamin Kogoya is a West Papuan academic who has a Master of Applied Anthropology and Participatory Development from the Australian National University and who contributes to Asia Pacific Report. From the Lani tribe in the Papuan Highlands, he is currently living in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz

![]()