ANALYSIS: By David Engel, Albert Zhang and Jake Wallis

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) has analysed thousands of suspicious tweets posted in 2021 relating to the Indonesian region of West Papua and assessed that they are inauthentic and were crafted to promote the policies and activities of the Indonesian government while condemning opponents such as Papuan pro-independence activists.

This work continues ASPI’s research collaboration with Twitter focusing on information manipulation in the Indo-Pacific to encourage transparency around these activities and norms of behaviour that are conducive to open democracies in the region.

It follows our August 24 analysis of a dataset made up of thousands of tweets relating to developments in Indonesia in late 2020, which Twitter had removed for breaching its platform manipulation and spam policies.

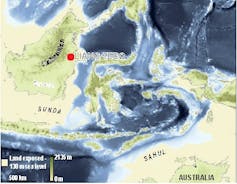

This report on Papua focuses on similar Twitter activity from late February to late July 2021 that relates to developments in and about Indonesia’s easternmost region.

This four-month period was noteworthy for several serious security incidents as well as an array of state-supported activities and events in the Papua region, then made up of the provinces of West Papua and Papua.

These incidents were among many related to the long-running pro-independence conflict in the region.

A report from Indonesia’s Human Rights Commission detailed 53 violent incidents in 2021 across the Papua region in which 24 people were killed at the hands of both security forces and the armed wing of the Free Papua Organisation (OPM) separatist movement, the West Papua National Liberation Army (TPNPB).

‘Armed criminal group’

Jakarta normally referred to this group by the acronym “KKB”, which stands for “armed criminal group”.

This upsurge in violence followed earlier cases involving multiple deaths. The most notorious took place in December 2018, when TPNPB insurgents reportedly murdered a soldier and at least 16 construction workers working on a part of the Trans-Papua Highway in the Nduga regency of Papua province (official Indonesian sources have put the death toll as high as 31).

The Indonesian government responded by conducting Operation Nemangkawi, a major national police (POLRI) security operation by a taskforce comprising police and military units, including additional troops brought in from outside the province.

The security operation led to bloody clashes, allegations of human rights abuses and extrajudicial killings, and the internal displacement of many thousands of Papuans, hundreds of whom, according to Amnesty International Indonesia, later died of hunger or illness.

Besides anti-insurgency actions, an important component of the operation was the establishment of Binmas Noken Polri, a community policing initiative designed to conduct “humanitarian police missions or operations” and assist “community empowerment” through programmes covering education, agriculture and tourism development.

“Noken” refers to a traditional Papuan bag that indigenous Papuans regard as a symbol of “dignity, civilisation and life”. Binmas Noken Polri was initiated by the then national police chief, Tito Karnavian, the same person who created the recently disbanded, shadowy Red and White Special Task Force highlighted in our August 24 report.

A key development occurred in April 2021 when pro-independence militants killed the regional chief of the National Intelligence Agency (BIN) in an ambush. Coming on the back of other murders by independence fighters (including of two teachers alleged to be police spies earlier that month), this prompted the government to declare the KKB in Papua—that is, the TPNPB “and its affiliated organisations”—”terrorists” and President Joko Widodo to order a crackdown on the group.

9 insurgents killed

Nine alleged insurgents were killed shortly afterwards.

In May 2021, hundreds of additional troops from outside Papua deployed to the province, some of which were part of an elite battalion nicknamed “Satan’s forces” that had earned notoriety in earlier conflicts in Indonesia’s Aceh province and Timir-Leste.

During the same month, there were large-scale protests in Papua and elsewhere over the government’s moves to renew and revise the special autonomy law, under which the region had enjoyed particular rights and benefits since 2001.

The protests included demonstrations staged by Papuan activists and students in Jakarta and the Javanese cities of Bandung and Yogyakarta from May 21-24. The revised law was ushered in by Karnavian, who was then (and is still) Indonesia’s Home Affairs Minister.

The period also saw ongoing preparations for the staging of the National Sports Week (PON) in Papua. Delayed by one year because of the covid-19 pandemic, the event eventually was held in October at several specially built venues across the province.

The dataset we analysed represents a diverse collection of thousands of tweets put out under such hashtags as #BinmasNokenPolri, #MenolakLupa (Refuse to forget), #TumpasKKBPapua (Annihilate the Papuan armed criminal group), #PapuaNKRI (Papua unitary state of the Republic of Indonesia), #Papua and #BongkarBiangRusuh (Take apart the culprits of the riots).

Most were overtly political, either associating the Indonesian state with success and public benefits for Papuans or condemning the state’s opponents as criminals, and sometimes doing both in the same tweet.

Papuan Games tweets

Among several tweets under #Papua proclaiming that the province was ready to host the forthcoming PON thanks to Jakarta’s investment in facilities and security, 18 dispatched on June 25 proclaimed: “PAPUA IS READY TO IMPLEMENT PON 2020!!! Papua is safe, peaceful and already prepared to implement PON 2020. So there’s no need to be afraid. Shootings by the KKB … are far from the PON cluster [the various sports facilities] … Therefore everyone #ponpapua #papua”.

Many tweets were clearly aimed at shaping public perceptions of the pro-independence militia and others challenging the state.

Under #MenolakLupa in particular, numerous tweets related to past and contemporary acts of violence by the pro-independence militants. Two sets of tweets from March 22 and 24 that recall the 2018 attack at Nduga are especially noteworthy, in that both injected the term “terrorist” into the armed criminal group moniker that the state had been using hitherto, making it “KKTB”. This was a month before the formal designation of the OPM as a “terrorist” organisation.

As if to stress the OPM’s terrorist nature, subsequent tweets under #MenolakLupa carried through with this loaded terminology. For example, tweets on June 15 stated that in 2017 “KKTB committed sexual violence” against as many as 12 women in two villages in Papua.

A fortnight later, another set of tweets said that in 2018 the “armed terrorist criminal group” had held 14 teachers hostage and had taken turns in raping one of them, causing her “trauma”. Others claimed former pro-independence militants had converted to the cause of the Indonesian unitary state and therefore recognised its sovereignty over Papua.

Some tweets relate directly to specific contemporary events. Examples are flurries of tweets posted on July 24-25 in response to the protests against the special autonomy law’s renewal that highlight the alleged irresponsibility of demonstrations during the pandemic, such as: “Let’s reject the invitation to demo and don’t be easily provoked by irresponsible [malign] people. Stay home and stay healthy always.”

Others are tweets put out under #TumpasKKBPapua after the shooting of the two teachers, such as: “Any religion in the world surely opposes murder or any other such offence, let alone of this teacher. Secure the land of the Bird of Paradise.”

Warning over ‘hoax’ allegations

Other tweets warn Papuans not to succumb to “hoax” allegations about the security forces’ behaviour or other claims by overseas-based spokespeople such as United Liberation Movement of West Papua’s Benny Wenda and Amnesty International human rights lawyer Veronica Koman.

Tweets on April 1 under #PapuaNKRI, for example, warned recipients not to “believe the KKB’s Media Propaganda, let’s be smart and wise in using the media lest we be swayed by fake news.”

Many of the tweets in the dataset are strikingly mundane, with content that state agencies already were, or would have been, publicising openly. A tweet on February 27 under #Papua, for example, announced that the Transport Minister would prioritise the construction of transport infrastructure in the two provinces.

Those under #BinmasNokenPolri often echoed advice that receivers of the tweet could just as easily see on other media, such as POLRI’s official Binmas Noken website.

Some were public announcements about market conditions and community policing events where, for example, people could receive government assistance such as rice, basic items and other support.

Most reflected Binmas Noken’s community engagement purpose, ranging from a series on May 20 promoting a child’s “trauma healing” session with Binmas Noken personnel to another tweeted out on June 20 advising of a badminton contest involving villages and police arranged under the Nemangkawi Task Force.

‘Healthy body, strong spirit’

A further 34 tweets on June 20 advised that “inside a healthy body is a strong spirit”, of which the first nine began with the same broad sentiment expressed in the Latin motto derived from the Roman poet Juvenal, “Mens sana in corpore sano.” (Presumably, after this first group of tweets it dawned on the sender that his or her classical erudition was likely to be lost on indigenous Papuan residents.)

As with the tweets analysed in our August 24 report, based on behavioural patterns within the data, we judge that these tweets are likely to be inauthentic—that is, they were the result of coordinated and covert activity intended to influence public opinion rather than organic expressions by genuine users on the platform.

Without conclusively identifying the actors responsible, we assess that the tweets mirror the Widodo government’s general position on the Papuan region as being an inalienable part of the Indonesian state, as well as the government’s security policies and development agenda in the region.

The vast majority are purposive: by promoting the government’s policies and activities and condemning opponents of those policies (whether pro-independence militia or protesters), the tweets are clearly designed to persuade recipients that the state is providing vital public goods such as security, development and basic support in the face of malignant, hostile forces, and hence that being Indonesian is in their interests.

Dr David Engel is senior analyst on Indonesia in ASPI’s Defence and Strategy Programme. Albert Zhang is an analyst with ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre. His research interests include information and influence operations, and disinformation. Dr Jake Wallis is the Head of Programme, Information Operations and Disinformation with ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre. This article is republished from The Strategist with permission.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz