MIL OSI Analysis –

Source: Council on Hemispheric Affairs – Analysis-Reportage:

Headline: Will the U.S.-Cuban rapprochement affect the relationship between the European Union and Cuba?

By: Clément Doleac, Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs, and Lucas G. Guest Contributor for the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

The European Union (EU), which has been working to normalize its ties with Cuba since 2010, defined the announcement of the reestablishment of the United States-Cuban relations as a “historical turning point.”1 The EU foreign affairs head, Ms. Frederica Mogherini said that “another wall has started to fall,” and that the European Union is willing to “expand relations with all parts of Cuban society.”2Representatives from Cuba and the EU will meet in March 2015 for a third round of negotiations aimed at normalizing relations after a decade tainted by the already recognized hypocritical European Union Common Position which pressed Cuba to discuss human rights and the role of civil society in the Cuban politics.3 These new negotiations can not help but bring on a high level of uncertainty because the turn in US-Cuban relations will impact EU-Cuba relations. Among other concerns, the economic standing of the European Union in Cuba as its second largest trading partner remains at risk.4

EU common position and the Progressive Improvement of EU-Cuba Relationship

In 1996, the then-15 EU member states adopted a Common Position (CP) related to Cuba.5 Under conservative Spanish leadership this position supported the latest U.S. round of sanctions against Cuba, the Helms-Burton Act, which had the clear objective to tighten restrictions against the Castro regime.6 The U.S. and EU intended to force the Cuban government to reform different sectors of its economy and society, and its political system, including the human rights situation.7

Unsurprisingly, the CP was strongly criticized by Cuban authorities and led to a political stalemate between the EU and Cuba. Despite such a tense political situation, European companies were among the first to invest in Cuba when the government loosened economic restrictions in 1995, know as the “special period in times of peace” following the Soviet Union’s collapse which resulted in Cuba’s GDP falling 30% in 4 years.8However, European Companies had to comply with the extremely strict and restrictive application of rules on foreign investments imposed by the Cuban government such as the obligation to submit to 50/50 Joint-Venture with the State, the difficulties to repatriate dividends, and the impossibility to manage human resources directly. Even with the CP, the EU had always been significantly less strict than the United States toward Cuba.9The EU gradually improved such ties with Cuba during the last two decades. In fact, 18 member states of the European Union have signed cooperation agreements with Cuba.10 Also, as one observer put it, “[the EU has] never excluded Cuba from participating in their summits with Latin America and the Caribbean, such as the Iberoamerican conferences of heads of states and government since 1992, and the Latin America and Caribbean-European Union summit gatherings since 1994.”11

However, in July 2003, several independent journalists, trade union activists, and dissidents were arrested across Cuba, and accused of conspiracy for cooperating with the Director of the U.S. Interest Section in Cuba, James Cason.12The accusations were based on diplomatic invitations of dissidents to attend official receptions, in order to symbolically further their struggle against political repression.13 Seventy-five persons were sentenced to six to 30 years in jail.14Consequently, the EU Council froze its diplomatic ties with Cuba, halting all cooperation and development aid that existed before. In addition to clamping down on the US-financed dissent, Fidel Castro apparently felt that the previous economic opening was too much, too fast. Thus, he reversed decision regarding the still small Cuban private sector (“cuentaspropistas”), and placed additional restrictions on Cuban economic liberties and foreign investments.15 Yet, it is fair to recognize that some foreign investors might have tried to escape the Kafkaesque Cuban system by illegal means, leading to corruption cases. As a result, the number of joint-venture companies was halved between 2001 and 2007 and the government used the occasion to seize some valuable assets.16

In 2004 Cuba released a number of dissidents and the EU revised its strategy to maintain more discrete contacts with local dissidents. After nearly two years of tensions passed, the EU chose not to invite opponents of the regime to official celebrations.17 Consequently, Cuba normalized its ties with a number of European countries, including France, Spain, and Germany.18It was not until 2006, when Fidel Castro handed his leadership in Cuba to his younger brother, Raul Castro, that this diplomatic conflict ended. However, it would take two more years for the EU to restart cooperation with Cuba after the release of the majority of the dissidents.

In 2008, Cuba was hit by three successive hurricanes, which caused significant damages in part of the country, crippling its economy, and leading to a partial default vis-à-vis its main trading partners. Since then, the European Commission has committed nearly €60 million for post-hurricane reconstruction, food security, climate change policies, renewable energy, culture, and education in Cuba. The EU also allowed Cuba to take part in E.U.-funded regional programs. 19

This pursuit of a more comprehensive approach toward Cuba was strengthened by the position of Spain, which has advocated since 2010 for a revised CP. At the time, Ms. Trinidad Jimenez, Spain Secretary of State, declared the CP to be a “discriminatory, inefficient and illegitimate” policy.20Still, for a policy change to occur, the unanimous support of the 27 EU member states was necessary. While several countries were supportive of the Common Position, mostly because of their past suffering of soviet authoritarism, other EU countries had a more flexible idea of what should be the nature of EU-Cuba relationship.21 On May 12, 2010, the first Country Strategy Paper was adopted on Cuba, including an additional fund of €20 million during the period 2011-2013 in order to pursue the EU’s ongoing cooperation, as well as an additional aid of €4 million in order to help the Cuban population affected by the Hurricane Sandy in November 2012.22After the 6th Cuban Communist Party (CCP) Congress in 2011 revealed its lineamientos (“guidelines”) to “actualize [the] Cuban economic model,” as well as introduced the first reforms started to be implemented sin prisas pero sin pausas (“slowly but surely”) by Raul Castro. The EU-Cuba relationship continued to improve.23

Finally, during the first months of 2014, all the EU member states agreed to give a negotiation mandate to the EU’s foreign policy chief to discuss and renew EU-Cuba partnership. The CP and its flexibility led to a significant improvement of the EU-Cuba relationship by encouraging Cuban government policies to move towards more liberal economic and political practices.

The EU as Cuba’s 2nd largest economic partner

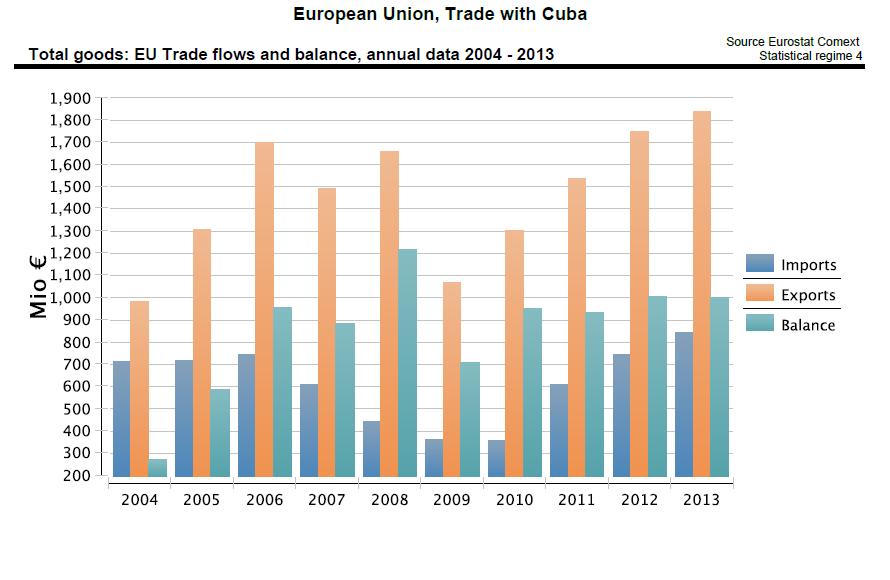

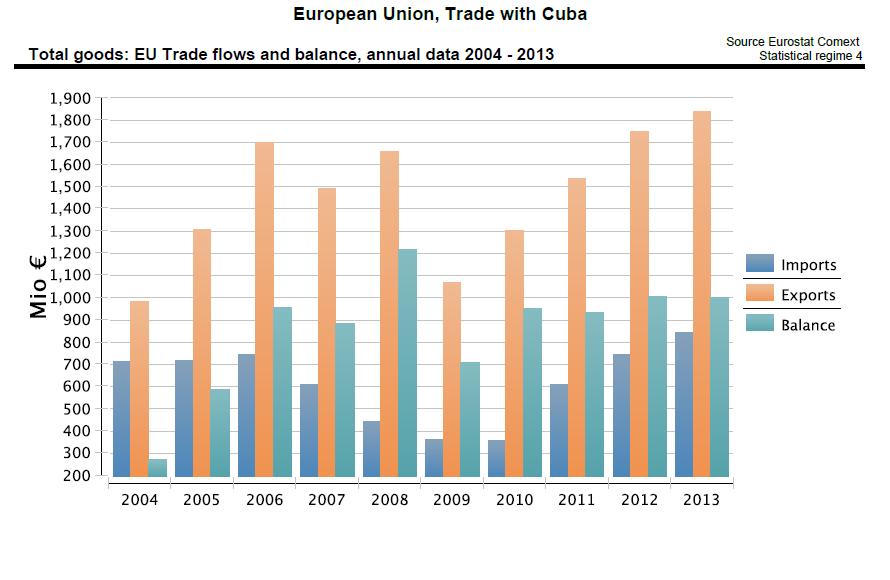

The EU is an important economic partner of Cuba, filling the void US trade sanctions produced. Trade between the EU and Cuba is now dynamic, representing a positive balance for the European Union. Among the top 10 trading partners of Cuba, four countries are member states of the EU: Spain is third, Holland seventh, Italy ninth and France tenth.24 In 2013, the European Union imported €837 million from Cuba and exported €1,834 million to Cuba, representing a nearly €1 billion surplus (see Figure 1).25In 2013, transactions with the European Union and the rest of the continent accounted for 28.3 percent of Cuba’s foreign trade. This statistic shows that 36.7 percent of Cuban exports go to the EU market and 25.9 percent of national imports come from that region.

Figure 1:

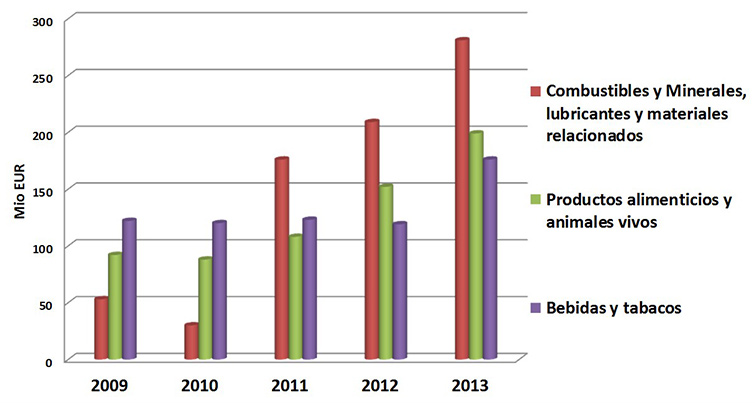

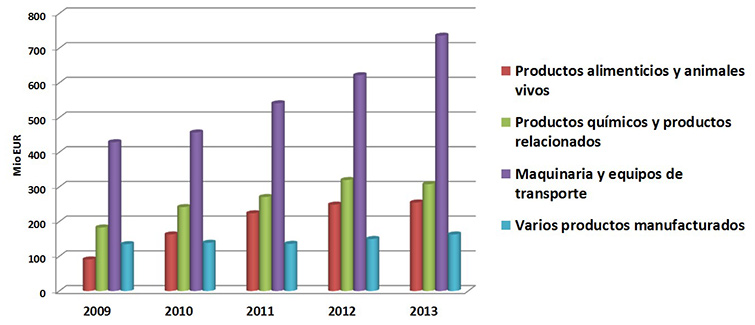

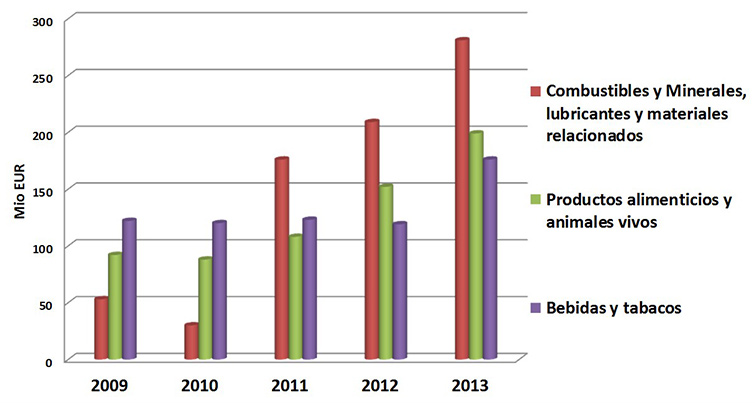

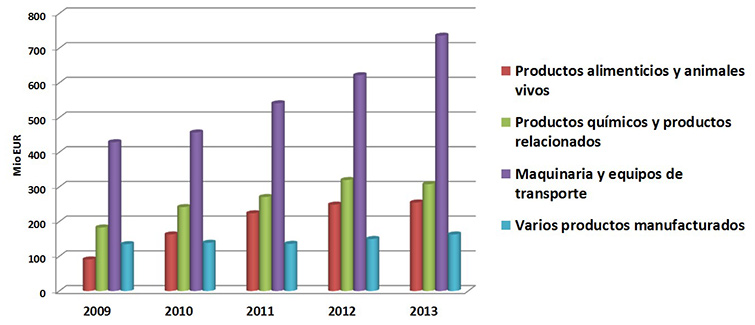

As shown in Figures 2 and 3, the trade relationship between the EU and Cuba is concentrated in two kinds of goods: agricultural and industrial products. Agriculture represents 42.5 percent of EU imports from Cuba while Cuban imports from the EU are 84.7 percent industrial products. On one hand, the EU imports foodstuffs, beverages, and tobacco, including rum, cigars and sugar derivatives (40.8 percent) and mineral products such as nickel and scrap metal (33.6 percent). On the other hand, the EU exports to Cuba machinery and appliances (34.5 percent), and products of the chemical, plastics and allied industries (13.4 percent).26

Figure 2: Exports from Cuba to the European Union

As shown in Figures 2 and 3, the trade relationship between the EU and Cuba is concentrated in two kinds of goods: agricultural and industrial products. Agriculture represents 42.5 percent of EU imports from Cuba while Cuban imports from the EU are 84.7 percent industrial products. On one hand, the EU imports foodstuffs, beverages, and tobacco, including rum, cigars and sugar derivatives (40.8 percent) and mineral products such as nickel and scrap metal (33.6 percent). On the other hand, the EU exports to Cuba machinery and appliances (34.5 percent), and products of the chemical, plastics and allied industries (13.4 percent).26

Figure 2: Exports from Cuba to the European Union

In Figure 2, minerals, fuels, lubricants and related materials appear in red, in green alimentary products and animals, and in purple beverages and tobacco. Source: See reference 26.

In Figure 2, minerals, fuels, lubricants and related materials appear in red, in green alimentary products and animals, and in purple beverages and tobacco. Source: See reference 26.

Figure 3: Exports from the European Union to Cuba by categories

In Figure 3 alimentary products and animals appear in red, in green chemical products, in purple the machinery and transportation equipment and in blue other manufactured products. Source: See reference 26.

It is easy to see that the trade relationship between Cuba and the EU is unbalanced: Cuba exports mostly primary products (85 percent of their trade total), while the EU exports manufactured ones (around 81 percent of their total exports).

27

EU-Cuba trade recently suffered a setback with the exemption of Cuba on January 1st, 2014 from the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP).

28 The Cuban exclusion is due to the way Cuba changed its method to calculate its nominal GDP in the early 2000s in order to give it a statistical boost of 15 percent.

29 Automatically, the country jumped to higher level in EU’s GSP ranking, making it a middle income nation. Aware that this new methodology could present such a risk, Cuban authorities preferred to keep their obscure statistics and reduce its market in Europe, in order to appear among the “developed economies.”

30 Thus, under the new rules, taxes on Cuban cigars jumped from 7.8 percent to 26.9 percent in 2014.

31Despite being considered a part of the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States (ACP) since 2010, Cuba does not benefit from the ACP-EU Sugar Protocol, and therefore loose an advantageous tariff for its sugar.

32

Other EU Economic Presence in Cuba

The EU presence in Cuba is not only a trade relationship. European companies are present in many areas of Cuba’s economy. For the last 20 years, the EU is the second largest provider of tourists to Cuba. Tourism brings the cash-starved Cuban economy $1 to 2 billion USD every year, and is its 3

rd source of cash after medical services and remittances.

33 Therefore, it is no coincidence that the Cuban tourism industry is dominated by European operators from Spain, France, and Germany. But, since Obama’s easing measures in 2008, Cuban-Americans and authorized (or not) American visitors have also significantly increased.

34

Also, one would be surprised to see how many French Peugeots and Renaults are driven along with 1950s American Chevies and 1970s Soviet Ladas in Havana’s streets. Spanish Seats and Italian Fiats are not unknown either. European exporters of food, machinery, industry, and chemicals also represent an alternative to cheap but unreliable Asian materials, antique Russian products and, of course, banned American goods. To finance this trade, European banks are also vital to the Cuban economy. Indeed, it is clear that European companies benefit partly from the absence of American competitors in Cuba thatwere forced out by U.S. sanctions.

The Damocles Sword of the Helms-Burton Act for European Businesses

The United States government has imposed a continuous embargo on Cuba since 1961 strengthening it twice, through the 1992 Cuba Democracy Act and the 1996 Helms-Burton Act, which contributed significantly to Havana’s dire economic situation, and.

35 The latter act installed the embargo as an entrenched law, while it previously was an executive authority action, conditioning its removal by free and fair elections in Cuba and excluding the Castro brothers, among many other conditions (Title I and II).

36 The Helms-Burton Act, far from being of any help with the development of democracy in Cuba, has led to a continued grip of the Castro brothers on the island, and raised opposition towards the embargo amongst the international community.

Even though trade in Cuba is not impossible after Helms-Burton, it is considerably more complicated, leading to an increase in the cost of operations. Among the many obstacles, European businesses can face fines and sanctions for activities such as the use of the US dollar for their trade with Cuba (which Cuba oddly oblige its trading partners to use), the intermediation of a US-based clearing house for money transfer, and the trade of any goods or products composed of more than 10 percent of US based components, such as an operating system running on Microsoft Windows. Shipping is also problematic as a boat can not deliver goods to Cuba. In the U.S., boats have to wait more than 3 months before being able to stop in a U.S. port or to operate for a U.S. company, increasing the cost of importation to Cuba. In the end, the U.S. suffered retaliatory measures from several countries, including Mexico and Canada, and the EU, all close allies of the United States.

37 When the legislation was approved several companies suffered sanctions, such as the Canadian mining company Sherritt International Corporation of Toronto. Many Mexican companies such as Mexican Cements (

Cementos Mexicanos, CEMEX) and potential investors in Cuba withdrew from Cuba.

38

In theory, the financial sector in Cuba should be particularly concerned with the restrictions of the Helms-Burton Act because of the nationalization and expropriation of the banks by the Cuban government in 1960. In fact, the Helms-Burton Act Title III allows U.S. Citizens and Cuban-Americans who suffered nationalization of their property by the Cuban Revolution to file lawsuits against international companies doing business with such properties.

39 On October 13, 1960, through Law 1890 and 1891, Fidel Castro nationalized 37 banks which were the property of rich Cubans and American citizens, and on September 17, 1960, the Cuban government nationalized the North American banks on the island.

40 With these three measures the financial system in Cuba was completely under control of the revolutionary government and, therefore, potentially included under the Helms-Burton Act’s Title III.

The EU attacked the Helms Burton Act in the World Trade Organization (WTO), fearing a dangerous precedent of U.S. extraterritorial application of its national laws, and threatened to establish a “blacklist” of U.S. companies filing suits against European firms not in accordance with the Helms Burton Act.

41 This conflict was resolved in May 1998 during EU-U.S. summit through the acceptance by US executive power to protect EU companies from any penalties called for in Helms-Burton Act.

42 However, protection of European companies has still not been enacted by U.S. Congress, even if they are able to benefit in any manner from an executive branch waiver renewed every six months.

43 The Sword of Damocles remains present and highlights the hypocrisy of U.S. diplomacy by never enacting the agreement, even with its close allies.

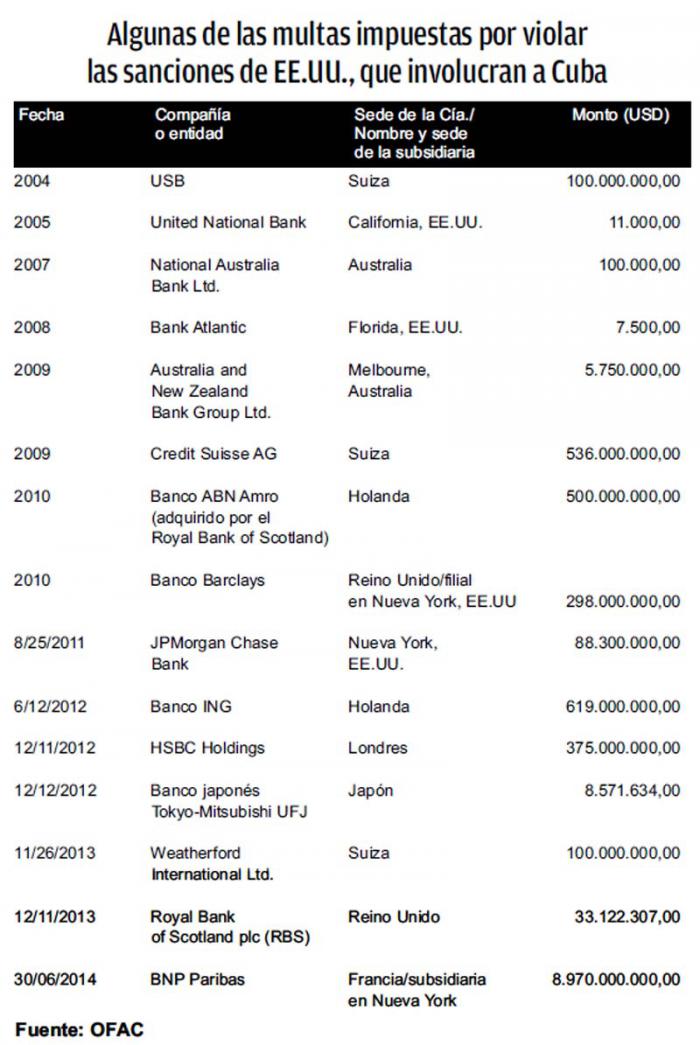

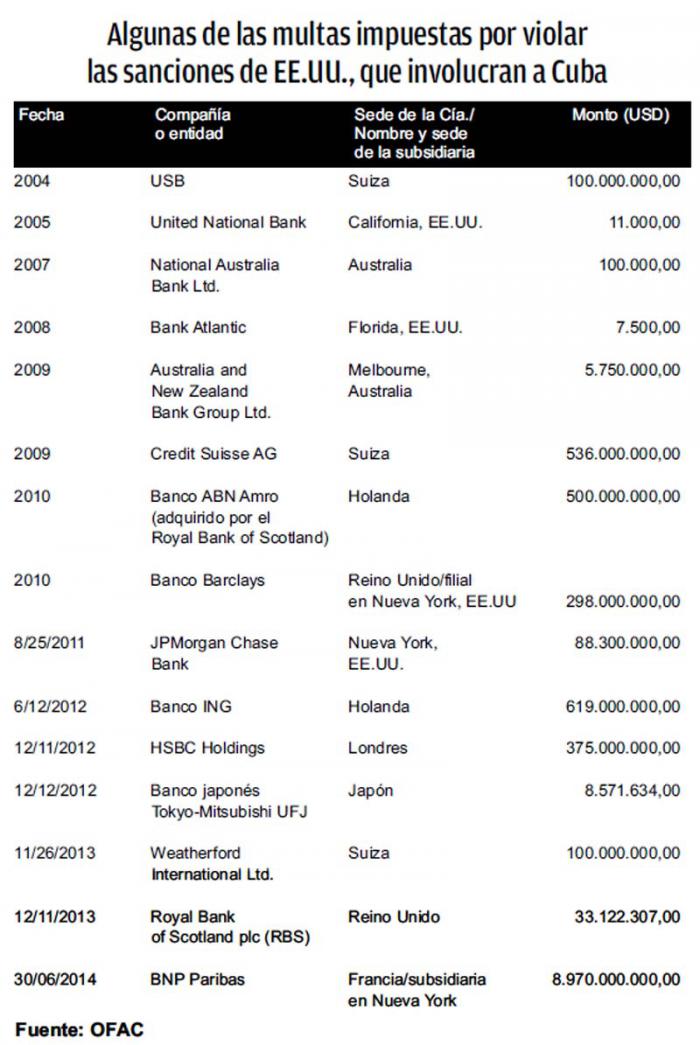

However, even if every President of the United States provided a waiver for the Title III of the Helms-Burton Act, many enterprises suffered fines, specifically in the banking and finance sector, mainly because of the use of U.S. based subsidiaries and of U.S. dollar for their transactions with Cuba.

44

One such enterprise was the French bank BNP-Paribas because of its operation in Cuba and Iran since its U.S. based subsidiaries. As stated by

CubaStandard, “the use of U.S. dollars in transactions with Cuba and other U.S.-sanctioned countries violates U.S. laws. SWIFT payments in U.S. dollars must clear through U.S.-based computers, and that violates U.S. sanctions, policy enforcers in Washington insist.”

45

Figure 4: Some of the fines imposed for violating US sanctions, involving Cuba. Source: Granma 46

Other enterprises which suffered these sanctions, as displayed in the Figure 4, are the

DN Amro Bank from Netherlands, the U.S. based

JP Morgan Chase., the German

Commerzbank, the Dutch’s bank ING, the Swiss’s bank

Credit Suisse, Bank of Nova Scotia, as well as many others.

47 European companies preferred to not comply with their own laws rather than risk losing their licenses in the US or being forbidden to use the access to U.S dollar.

48

The EU urged the U.S. government to change its approach towards Cuba numerous times. In 2014, the EU emphasized the “existing restrictions on rights and freedoms” in Cuba, but also was very positive talking about “the adoption by the Cuban Parliament in August 2011 of a package of economic and social reforms […] that will address the key concerns of the Cuban population”.

49 The EU statement emphasized the disastrous effects of the U.S. embargo, claiming that it “contributes to the economic problems in Cuba, negatively affecting the living standards of the Cuban people and having consequences in the humanitarian fields as well.”

50 The actions of the UN institutions in Cuba, such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) or the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) are also complicated by the embargo and its financial effects, complicating their day-to-day work and communication with their headquarters in New-York. Still the U.S. government reminded resolute in its stance, until recently, and the EU never did more to oppose the U.S. government.

51

The Re-Opening of U.S.-Cuban Relations and Its Affect on EU-Cuban Trade

The recent changes announced in U.S. policy on Cuba might alleviate numerous restrictions, but the change will come slowly and will require much strength from the White House. As stated by

CubaNow, the lobby of Cuban Americans is calling for a new approach towards Cuba and the U.S. executive branch can already freely grant exceptions for commerce and trade, for export and sale of goods and services, license U.S. travelers to Cuba to have access to U.S. financial services, to expand general license travel related to business in the financial services sector, travel and hospitality-related industries as well as banking, insurance, credit cards, and consumer products related to travel. President Obama can also, without Congressional support, allow the International Financial Institutions (IFIs), such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), to assist Cuba technically. Cuba remains excluded from IFI’s as any new member indirectly needs U.S approval.

52 Recent announcements might change the course of the restrictions, but it is not clear yet how far US companies can go and it is even less clear for foreign companies.

United States Interest Section in Havana

United States Interest Section in Havana

However, one thing is certain, EU businesses will suffer if the US-Cuban relationship is fully reestablished without trade and economic restrictions. For example, the food-processing industry will experience difficulties because of the additional costs for the importation of products from the EU compared to the reduced costs from the United States. The EU stands to lose a $150 million wheat market in Cuba if the embargo is lifted.

53 Wheat is the second largest import of Cuba, after refined oil, and the country bought nearly $149 million dollars of wheat from the EU last year, mainly from France.

54Because of its unsuitable climate for growing wheat, the island represents the biggest market in the Caribbean, and also a natural geographic market, for the U.S.

Cubans already buy corn and food stuffs from the U.S. making it its 7

th trading partner and Steve Nicholson, Vice President for Food and Agriculture Research at Rabo Agrifinance in St Louis has stated, “Cuba would be foolish not to be a good customer given the close proximity to the U.S.”

55According

to

Bloomberg the “grain shipping costs to Cuba from the U.S. Gulf are in the range of $6 to $7 a ton, while for France they’re more like $20 to $25 a ton.”

56The EU is not the only region that will suffer from a reestablishment of mutually beneficial U.S.-Cuban relationship. For example, Cuba has to import milk powder from New Zealand, even though the U.S is the largest milk powder producer in the world. The cost will be incredibly lower for Cuba to import from 90 miles away rather than across the Pacific.

In other sectors, the U.S. will have to fight to gain market shares in Cuba. Even if the U.S. strategy of “cleaning the field” by forcing the European banks to shut their representation and cut most of their links with Cuba was quite successful, European banks still process credit cards and have an advantage over their American competitors there. At the end of the day, Cuban administrators and Cuban public trading agencies are the ones that will decide who comes in or not.

Expectations for the future

It would be very surprising if the U.S. Congress chose to lift the embargo and repeal the Helms Burton Act before the 2016 Presidential elections. The 2016 elections dictate that there is at least a 2-3 year window of opportunity for non-US companies in Cuba. The United States still needs to clarify its position regarding several subjects that will be a source of tension with Cuban authorities, such as the Guantanamo Bay military base and the property claims by the enterprises and properties nationalized in 1960.

57

The U.S. Foreign Claims Settlement Commission also ratified nearly 6,000 property claims by U.S. corporations and citizens for a value estimated at $1.85 billion.

58 Today, the United States government claims $7 billion because of the interests.

59 This problem is also amplified by Cuban Americans, who are now U.S. citizens and are also eligible for compensation, against the international jurisprudence applying for such cases.

60 The U.S. State Department estimates the number of potential claims around 200,000 for an estimated amount of tens of billions of dollars.

61 The Cuban government acknowledges the legitimacy of U.S. claims, even if it also asks for counter-claims of $181 billion because of the damage done by the U.S. embargo and the CIA’s secret war on Cuba. For now, the Cuban authorities deny the legitimacy of Cuban Americans demands.

62

Also, it seems quite unlikely that the Cubans will show more interest toward U.S. companies than what is needed to keep them in the game and maintain their pressure on U.S. politicians. If we believe the Cuban response to their partners’ concern of being left on the side of the road, Cubans will not forget those who were on their side during the last decades. Undoubtedly these problems are going to take a long time to be solved, and the U.S. Cuban economic relationship will need decades to reach its full potential. During that time, the EU firms and government cooperation are still free to invest in the field and to create privileged links with Cuba.

By: Clément Doleac, Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs, and Lucas G. Guest Contributor for the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action.

Featured images by the authors.

References:

– –

]]>

As shown in Figures 2 and 3, the trade relationship between the EU and Cuba is concentrated in two kinds of goods: agricultural and industrial products. Agriculture represents 42.5 percent of EU imports from Cuba while Cuban imports from the EU are 84.7 percent industrial products. On one hand, the EU imports foodstuffs, beverages, and tobacco, including rum, cigars and sugar derivatives (40.8 percent) and mineral products such as nickel and scrap metal (33.6 percent). On the other hand, the EU exports to Cuba machinery and appliances (34.5 percent), and products of the chemical, plastics and allied industries (13.4 percent).26

Figure 2: Exports from Cuba to the European Union

As shown in Figures 2 and 3, the trade relationship between the EU and Cuba is concentrated in two kinds of goods: agricultural and industrial products. Agriculture represents 42.5 percent of EU imports from Cuba while Cuban imports from the EU are 84.7 percent industrial products. On one hand, the EU imports foodstuffs, beverages, and tobacco, including rum, cigars and sugar derivatives (40.8 percent) and mineral products such as nickel and scrap metal (33.6 percent). On the other hand, the EU exports to Cuba machinery and appliances (34.5 percent), and products of the chemical, plastics and allied industries (13.4 percent).26

Figure 2: Exports from Cuba to the European Union

In Figure 2, minerals, fuels, lubricants and related materials appear in red, in green alimentary products and animals, and in purple beverages and tobacco. Source: See reference 26.

In Figure 2, minerals, fuels, lubricants and related materials appear in red, in green alimentary products and animals, and in purple beverages and tobacco. Source: See reference 26.

Other enterprises which suffered these sanctions, as displayed in the Figure 4, are the DN Amro Bank from Netherlands, the U.S. based JP Morgan Chase., the German Commerzbank, the Dutch’s bank ING, the Swiss’s bank Credit Suisse, Bank of Nova Scotia, as well as many others.47 European companies preferred to not comply with their own laws rather than risk losing their licenses in the US or being forbidden to use the access to U.S dollar.48

The EU urged the U.S. government to change its approach towards Cuba numerous times. In 2014, the EU emphasized the “existing restrictions on rights and freedoms” in Cuba, but also was very positive talking about “the adoption by the Cuban Parliament in August 2011 of a package of economic and social reforms […] that will address the key concerns of the Cuban population”.49 The EU statement emphasized the disastrous effects of the U.S. embargo, claiming that it “contributes to the economic problems in Cuba, negatively affecting the living standards of the Cuban people and having consequences in the humanitarian fields as well.” 50 The actions of the UN institutions in Cuba, such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) or the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) are also complicated by the embargo and its financial effects, complicating their day-to-day work and communication with their headquarters in New-York. Still the U.S. government reminded resolute in its stance, until recently, and the EU never did more to oppose the U.S. government.51

The Re-Opening of U.S.-Cuban Relations and Its Affect on EU-Cuban Trade

The recent changes announced in U.S. policy on Cuba might alleviate numerous restrictions, but the change will come slowly and will require much strength from the White House. As stated by CubaNow, the lobby of Cuban Americans is calling for a new approach towards Cuba and the U.S. executive branch can already freely grant exceptions for commerce and trade, for export and sale of goods and services, license U.S. travelers to Cuba to have access to U.S. financial services, to expand general license travel related to business in the financial services sector, travel and hospitality-related industries as well as banking, insurance, credit cards, and consumer products related to travel. President Obama can also, without Congressional support, allow the International Financial Institutions (IFIs), such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), to assist Cuba technically. Cuba remains excluded from IFI’s as any new member indirectly needs U.S approval.52 Recent announcements might change the course of the restrictions, but it is not clear yet how far US companies can go and it is even less clear for foreign companies.

Other enterprises which suffered these sanctions, as displayed in the Figure 4, are the DN Amro Bank from Netherlands, the U.S. based JP Morgan Chase., the German Commerzbank, the Dutch’s bank ING, the Swiss’s bank Credit Suisse, Bank of Nova Scotia, as well as many others.47 European companies preferred to not comply with their own laws rather than risk losing their licenses in the US or being forbidden to use the access to U.S dollar.48

The EU urged the U.S. government to change its approach towards Cuba numerous times. In 2014, the EU emphasized the “existing restrictions on rights and freedoms” in Cuba, but also was very positive talking about “the adoption by the Cuban Parliament in August 2011 of a package of economic and social reforms […] that will address the key concerns of the Cuban population”.49 The EU statement emphasized the disastrous effects of the U.S. embargo, claiming that it “contributes to the economic problems in Cuba, negatively affecting the living standards of the Cuban people and having consequences in the humanitarian fields as well.” 50 The actions of the UN institutions in Cuba, such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) or the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) are also complicated by the embargo and its financial effects, complicating their day-to-day work and communication with their headquarters in New-York. Still the U.S. government reminded resolute in its stance, until recently, and the EU never did more to oppose the U.S. government.51

The Re-Opening of U.S.-Cuban Relations and Its Affect on EU-Cuban Trade

The recent changes announced in U.S. policy on Cuba might alleviate numerous restrictions, but the change will come slowly and will require much strength from the White House. As stated by CubaNow, the lobby of Cuban Americans is calling for a new approach towards Cuba and the U.S. executive branch can already freely grant exceptions for commerce and trade, for export and sale of goods and services, license U.S. travelers to Cuba to have access to U.S. financial services, to expand general license travel related to business in the financial services sector, travel and hospitality-related industries as well as banking, insurance, credit cards, and consumer products related to travel. President Obama can also, without Congressional support, allow the International Financial Institutions (IFIs), such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), to assist Cuba technically. Cuba remains excluded from IFI’s as any new member indirectly needs U.S approval.52 Recent announcements might change the course of the restrictions, but it is not clear yet how far US companies can go and it is even less clear for foreign companies.

United States Interest Section in Havana

However, one thing is certain, EU businesses will suffer if the US-Cuban relationship is fully reestablished without trade and economic restrictions. For example, the food-processing industry will experience difficulties because of the additional costs for the importation of products from the EU compared to the reduced costs from the United States. The EU stands to lose a $150 million wheat market in Cuba if the embargo is lifted.53 Wheat is the second largest import of Cuba, after refined oil, and the country bought nearly $149 million dollars of wheat from the EU last year, mainly from France.54Because of its unsuitable climate for growing wheat, the island represents the biggest market in the Caribbean, and also a natural geographic market, for the U.S.

Cubans already buy corn and food stuffs from the U.S. making it its 7th trading partner and Steve Nicholson, Vice President for Food and Agriculture Research at Rabo Agrifinance in St Louis has stated, “Cuba would be foolish not to be a good customer given the close proximity to the U.S.”55According to Bloomberg the “grain shipping costs to Cuba from the U.S. Gulf are in the range of $6 to $7 a ton, while for France they’re more like $20 to $25 a ton.”56The EU is not the only region that will suffer from a reestablishment of mutually beneficial U.S.-Cuban relationship. For example, Cuba has to import milk powder from New Zealand, even though the U.S is the largest milk powder producer in the world. The cost will be incredibly lower for Cuba to import from 90 miles away rather than across the Pacific.

United States Interest Section in Havana

However, one thing is certain, EU businesses will suffer if the US-Cuban relationship is fully reestablished without trade and economic restrictions. For example, the food-processing industry will experience difficulties because of the additional costs for the importation of products from the EU compared to the reduced costs from the United States. The EU stands to lose a $150 million wheat market in Cuba if the embargo is lifted.53 Wheat is the second largest import of Cuba, after refined oil, and the country bought nearly $149 million dollars of wheat from the EU last year, mainly from France.54Because of its unsuitable climate for growing wheat, the island represents the biggest market in the Caribbean, and also a natural geographic market, for the U.S.

Cubans already buy corn and food stuffs from the U.S. making it its 7th trading partner and Steve Nicholson, Vice President for Food and Agriculture Research at Rabo Agrifinance in St Louis has stated, “Cuba would be foolish not to be a good customer given the close proximity to the U.S.”55According to Bloomberg the “grain shipping costs to Cuba from the U.S. Gulf are in the range of $6 to $7 a ton, while for France they’re more like $20 to $25 a ton.”56The EU is not the only region that will suffer from a reestablishment of mutually beneficial U.S.-Cuban relationship. For example, Cuba has to import milk powder from New Zealand, even though the U.S is the largest milk powder producer in the world. The cost will be incredibly lower for Cuba to import from 90 miles away rather than across the Pacific.

A summary of All Right research findings (PDF, 120kb)

A summary of All Right research findings (PDF, 120kb)

NewsKitchen.eu is a joint venture between Multimedia Investments Ltd (NZ) and German journalist and author Ingo Petz.

NewsKitchen.eu provides up-to-the-minute aggregation of geopolitical information relevant to the Eurozone, Russian Federation, Belarus and the Baltic states.

Its content is published in the language of the state of origin and provides raw news reports focussing on governments, external powers, global bodies, including news on security, defence, intelligence, trade, economics, and finance.

NewsKitchen.eu is a joint venture between Multimedia Investments Ltd (NZ) and German journalist and author Ingo Petz.

NewsKitchen.eu provides up-to-the-minute aggregation of geopolitical information relevant to the Eurozone, Russian Federation, Belarus and the Baltic states.

Its content is published in the language of the state of origin and provides raw news reports focussing on governments, external powers, global bodies, including news on security, defence, intelligence, trade, economics, and finance.