Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Jack Vowles, Professor of Political Science, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington

Winston Peters has long been described as a populist, both in New Zealand and internationally. At different times during his career he has embraced the label.

As he said recently, populism to him “means that you’re talking to the ordinary people and you’re placing their views far higher than the beltway and the paparazzi”.

But across much of the world, political analysts and commentators see the politics of populism as a menace. Parties described as populist are often associated with the radical right, authoritarianism, xenophobia and a rejection of pluralism and diversity.

While Peters and New Zealand First have sometimes leaned in those directions, it’s been inconsistent and intermittent. The party has retained a significant number of Māori among its MPs, members and voters — including, of course, Peters himself.

At this point in the election campaign, however, New Zealand First’s problem is not populism but popularity. Polls show its support significantly below the 5% it needs to stay in parliament. Where have those voters gone?

Populism of the left

In our recently launched book on the 2017 New Zealand general election, drawing on data from the New Zealand Election Study (NZES), we argue that populism has another side: in its origins as a social movement, populism was of the left, not the right.

Those who originally called themselves populists sought to mobilise and unite the vast majority of people to challenge the excessive economic and political power of a narrow elite. This form of democratic populism emerged in New Zealand in a wave of reforms that, by the 1890s, had made the young country one of the first fully fledged representative democracies in the world.

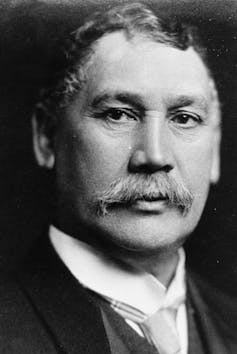

Populism flowered under the Liberal governments of the early 20th century, personified by the prime minister Richard Seddon (“King Dick”). His government championed the interests of the working class and small farmers by encouraging trade unionism and breaking up the big estates held by the colonial rich.

The Liberals were less successful at defending the interests of Māori. But New Zealand’s first Māori deputy prime minister and sometime acting prime minister was Liberal MP James Carroll (Ngāti Kahungunu) — not Winston Peters.

Inclusion versus exclusion

We define populism in two senses: first, as a set of democratic norms that takes seriously the idea of “the sovereignty of the people”; second, as rhetoric that uses populist language to attract support, but not necessarily for populist ends.

We also argue that it is necessary to distinguish between authoritarian or exclusionary populism, which seeks to divide the people by ethnicity or national origins, and inclusive populism, which seeks to build majorities on the foundations of what most members of a society have in common.

We found that in 2017 New Zealand populists were located predominantly on the left, with few exhibiting authoritarian views. For the minority of voters who expressed preferences for both populism and authoritarianism, their party of choice tended to be New Zealand First — the party that in 2017 won just over 7% of the vote and is now polling at 2% or less.

So, does the decline in support for New Zealand First in 2020 represent a shift in populist sentiment?

Where have authoritarian populists gone?

New Zealand First’s brand of populism over the past three years has shifted between the exclusive and the inclusive. In the 2017 election campaign, the party’s rhetoric was true to form, focusing on reducing immigration and a desire to give more voice to the regions.

NZES data show the majority of New Zealand First voters wanted the party to form a coalition with National, but a sizeable minority also wanted to see political change. Indeed, New Zealand First’s campaign policies in 2017 were closely aligned with Labour’s, with a few exceptions: water quality and climate change mitigation being the two most clearly incompatible.

Our study shows that in 2017 New Zealand First appealed to voters who were older, Pākehā, male, on low incomes and lived outside the major cities.

In the end, New Zealand First entered into a government with Labour, led by Jacinda Ardern, a relatively young woman whose rhetoric, feminism and policy orientation aligned with a more inclusive version of populism. This challenged some New Zealand First voters but won over others.

More recently, the issue of immigration has all but disappeared from the political agenda, removing New Zealand First’s key populist plank. Peters has been championing various versions of border reopening over the past three months, suggesting he may be an internationalist at heart, at least when the economy is at stake.

It’s too early to be sure where New Zealand’s small percentage of authoritarian populists have gone. Are they the roughly 2% that remain committed to New Zealand First? Or has National Party leader Judith Collins’ aggressive labelling of Labour as anti-farmer and anti-aspirational been gaining traction?

Or has the resolve with which Labour closed the borders struck a chord with New Zealand First’s authoritarians? Some recent polling analysis suggests much of the 2017 New Zealand First vote has indeed shifted to Labour.

The rise of moderate populism

Our analysis of the 2017 election reveals Ardern’s inclusionary campaign rhetoric was appealing. Voters found her likeable, competent and trustworthy. She also struck a chord with the onset of COVID-19. Her phrase “a team of 5 million” clearly evoked the populist ethos.

Trust in Ardern’s leadership, despite the centralised nature of our political institutions, has remained high. At the same time, satisfaction with our political process has not declined as it has in the other democracies, making a spike in authoritarian populism even less likely.

Those who fear and lament populism tend to see only the dark side of the phenomenon and often discount the idea that “the people” represent anything other than a threat. Liberal democratic critics of populism therefore admire or hanker after constitutional checks to insulate governments from public opinion.

While we concede that protection of human rights requires some limits on majorities, our analysis of contemporary New Zealand politics indicates that the best antidote to authoritarian populism is a democratic and inclusive form of moderate populism.

Certainly Ardern’s version of moderate populism has proved popular. With immigration not a focus this election, New Zealand First’s appeal to authoritarian populist voters appears to have all but disappeared. To know where these voters go next we will need to wait for the results of the 2020 New Zealand Election Study.

– ref. With the election looming and New Zealand First struggling in the polls, where have those populist votes gone? – https://theconversation.com/with-the-election-looming-and-new-zealand-first-struggling-in-the-polls-where-have-those-populist-votes-gone-147166