Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Douglas Tait, Senior Researcher, Southern Cross University

The Great Barrier Reef is one of Australia’s most important environmental and economic assets. It is estimated to contribute A$56 billion per year and supports about 64,000 full-time jobs, according to the Great Barrier Reef Foundation. However, the reef is under increasing pressure.

While much public attention is focused on the impacts of climate change on the Great Barrier Reef and the debate around its endangered status, water quality is also crucial to the reef’s health and survival.

Our new study, published today in the journal Environmental Science and Technology, found that previously unquantified groundwater inputs are the largest source of new nutrients to the reef. This finding could potentially change how the Great Barrier Reef is managed.

Too much of a good thing

Although nitrogen and phosphorous are essential to support the incredible biodiversity of the reef, too much nutrient can lead to losses of coral biodiversity and coverage. It also increases the abundance of algae and the ability of coral larvae to grow into adult coral, and impacts seagrass coverage and health, which is crucial for fisheries and biodiversity.

Nutrient enrichment can also promote the breeding success of crown-of-thorns starfish, whose increasing populations and voracious appetite for corals have decimated parts of the reef in recent decades.

Ashly McMahon, CC BY-ND

What are the sources of nutrients driving the degradation of the reef? Previous studies have focused on river discharge. According to one estimate, there has been a fourfold increase in riverine nutrient input to the Great Barrier Reef since pre-industrial times.

This past focus on rivers has emphasised reducing surface water nutrient inputs through changing regulations for land-clearing and agriculture, while neglecting other potential sources.

Read more:

Floods of nutrients from fertilisers and wastewater trash our rivers. Could offsetting help?

However, the most recent nutrient budget for the Great Barrier Reef found river-derived nutrient inputs can account for only a small proportion of the nutrients necessary to support the abundant life in the reef. This imbalance suggests large, unidentified sources of nutrients to the reef. Not knowing what these are may lead to ineffective management approaches.

With recent government funding of more than $200 million to tackle water quality on the reef which is largely focused on managing river water inputs, it is crucial to make sure other nutrient sources are not overlooked.

Douglas Tait, CC BY-ND

We found a new nutrient source

Our research team decided to try and track down this missing source of nutrients.

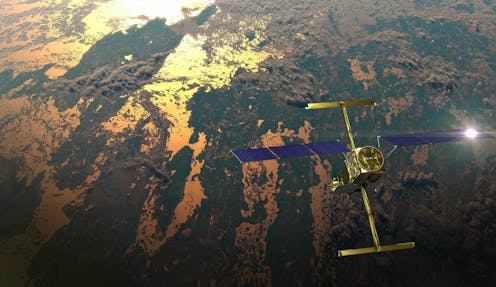

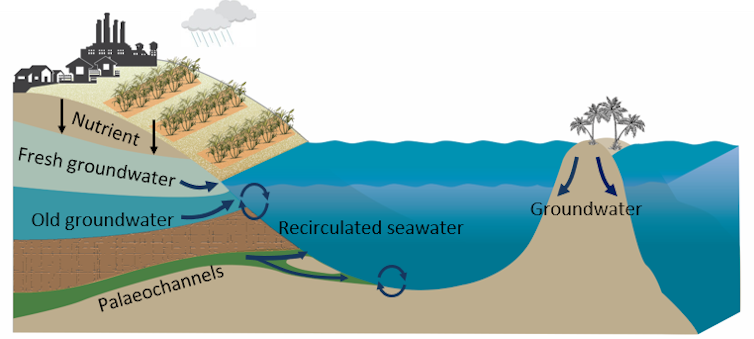

We used natural tracers to track groundwater inputs off Queensland’s coast. This allows us to quantify how much invisible groundwater flows into the Great Barrier Reef, along with the nutrients hitching a ride with this water. Our findings indicate that current efforts to preserve and restore the health of the reef may require a new perspective.

Our team collected data from offshore surveys, rivers and coastal bores along the coastline from south of Rockhampton to north of Cairns. We used the natural groundwater tracer radium to track how much nutrient is transported from the land and shelf sediments via invisible groundwater flows.

Ashly McMahon, CC BY-ND

We found that groundwater discharge was 10–15 times greater than river inputs. This meant roughly one-third of new nitrogen and two-thirds of phosphorous inputs came via groundwater discharge. This was nearly twice the amount of nutrient delivered by river waters.

Past investigations have revealed that groundwater discharge delivers nutrients and affects water quality in a diverse range of coastal environments, including estuaries, coral reefs, coastal embayments and lagoons, intertidal wetlands such as mangroves and saltmarshes, the continental shelf and even the global ocean.

In some cases, this can account for 90% of the nutrient inputs to coastal areas, which has major implications for global biologic production.

Nevertheless, this pathway remains overlooked in most coastal nutrient budgets and water quality models.

Ashly McMahon, CC BY-ND

A paradigm shift needed?

Our results suggest the need for a strategic shift in management approaches aimed at safeguarding the Great Barrier Reef from the effects of excess nutrients.

This includes better land management practices to ensure fewer nutrients are entering groundwater aquifers. We can also use ecological (such as seaweed and bivalve aquaculture, enhancing seagrass, oyster reefs, mangroves and salt marsh) and hydrological (increasing flushing where possible) practices at groundwater discharge hotspots to reduce excess nutrients in the water column.

The reuse of nutrient-rich groundwater for agriculture also needs to be explored as it represents an untapped and inexpensive nutrient source.

Importantly, unlike river outflow, nutrients in groundwater can be stored underground for decades before being discharged into coastal waters. This means research and strategies to protect the reef need to be long-term. The potential large lag time may lead to significant problems in the coming decades as the nutrients now stored in underground aquifers make their way to coastal waters regardless of changes to current land use practices.

Ashly McMahon, CC BY-ND

The understanding and ability to manage the sources of nutrients is pivotal in preserving global coral reef systems.

While we need to reduce the impact of climate change on this fragile ecosystem, we also need to adjust our policies to manage nutrient inputs and safeguard the Great Barrier Reef for generations to come.

Read more:

Out of danger because the UN said so? Hardly – the Barrier Reef is still in hot water

![]()

The authors receive funding from the Australian Research Council, the Herman Slade Foundation and the Great Barrier Reef Foundation.

Damien Maher receives funding from the Australian Research Council, Hermon Slade Foundation, Great Barrier Reef Foundation.

– ref. There’s a hidden source of excess nutrients suffocating the Great Barrier Reef. We found it – https://theconversation.com/theres-a-hidden-source-of-excess-nutrients-suffocating-the-great-barrier-reef-we-found-it-214364