ANALYSIS: By Kalinga Seneviratne in Singapore

In the aftermath of Palestinian group Hamas’ terror attack inside Israel on October 7 and the Israeli state’s even more terrifying attacks on Palestinian urban neighbourhoods in Gaza, the media across many parts of Asia tend to take a more neutral stand in comparison with their Western counterparts.

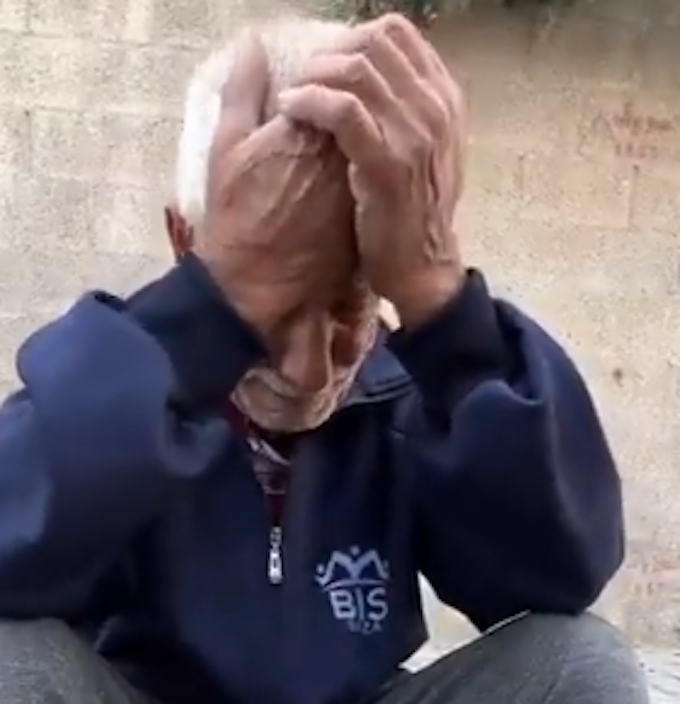

A lot of sympathy is expressed for the plight of the Palestinians who have been under frequent attacks by Israeli forces for decades and have faced ever trauma since the Nakba in 1948 when Zionist militia forced some 750,000 refugees to leave their homeland.

Even India, which has been getting closer to Israel in recent years, and one of Israel’s closest Asian allies, Singapore, have taken a cautious attitude to the latest chapter in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.

Soon after the Hamas attacks in Israel, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi tweeted that he was “deeply shocked by the news of terrorist attacks”.

He added: “We stand in solidarity with Israel at this difficult hour.” But, soon after, his Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) sought to strike a balance.

Addressing a media briefing on October 12, MEA spokesperson Arindam Bagchi reiterated New Delhi’s “long-standing and consistent” position on the issue, telling reporters that “India has always advocated the resumption of direct negotiations towards establishing a sovereign, independent and viable state of Palestine” living in peace with Israel.

Singapore has also reiterated its support for a two-state solution, with Law and Home Affairs Minister K. Shanmugam telling Today Daily that it was possible to deplore how Palestinians had been treated over the years while still unequivocally condemning the terrorist attacks carried out in Israel by Hamas.

“These atrocities cannot be justified by any rationale whatsoever, whether of fundamental problems or historical grievances,” he said.

“I think it’s fair to say that any response has to be consistent with international law and international rules of war”.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi has blamed the rapidly worsening conflict in the Middle East on a lack of justice for the Palestinian people.

Lack of justice for Palestinians

“The crux of the issue lies in the fact that justice has not been done to the Palestinian people,” Beijing’s top diplomat said in a phone call with Brazil’s Celso Amorim, a special adviser to Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, according to Japan’s Nikkei Asia.

The call came just ahead of an emergency meeting of the UN Security Council on October 13 to discuss the Israel-Hamas war. Brazil, a non-permanent member, is chairing the council this month.

Indonesian President Jokowi Widodo called for an end to the region’s bloodletting cycle and pro-Palestinian protests have been held in Jakarta.

“Indonesia calls for the war and violence to be stopped immediately to avoid further human casualties and destruction of property because the escalation of the conflict can cause greater humanitarian impact,” he said.

“The root cause of the conflict, which is the occupation of Palestinian land by Israel, must be resolved immediately in accordance with the parameters that have been agreed upon by the UN.”

Indonesia, which is home to the world’s largest Muslim population, has supported Palestinian self-determination for a long time and does not have diplomatic relations with Israel.

But, Indonesia’s foreign ministry said 275 Indonesians were working in Israel and were making plans to evacuate them.

Sympathy for the Palestinians

Meanwhile, Thailand said that 18 of their citizens have been killed by the terror attacks and 11 abducted.

In the Philippines, Foreign Affairs Secretary Enrique Manalo said on October 10 that the safety of thousands of Filipinos living and working in Israel remained a priority for the government.

There are approximately 40,000 Filipinos in Israel, but only 25,000 are legally documented, according to labour and migrant groups, says Benar News, a US-funded Asian news portal.

According to India’s MEA spokesperson Bagchi, there are 18,000 Indians in Israel and about a dozen in the Palestinian territories. India is trying to bring them home, and a first flight evacuating 230 Indians was expected to take place at the weekend, according to the Hindu newspaper.

It is unclear what such large numbers of Asians are doing in Israel. Yet, from media reports in the region, there is deep concern about the plight of civilians caught up in the clashes.

Benar News reported that Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim has spoken with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan about resolving the Palestine-Israel conflict according to UN-agreed parameters.

Also this week, the Malaysian government announced it would allocate 1 million ringgit (US$211,423) in humanitarian aid for Palestinians.

Western view questioned

Sympathy for the Palestinian cause is reflected widely in the Asian media, both in Muslim-majority and non-Muslim countries. The Western unequivocal support for Israel, particularly by Anglo-American media, has been questioned across Asia.

Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post’s regular columnist Alex Lo challenged Hamas’ “unprovoked” terror attack in Israel, a narrative commonly used in Western media reporting of the latest flare-up.

“It must be pointed out that what Hamas has done is terrorism pure and simple,” notes Lo.

“But such horrors and atrocities are not being committed by Palestinian militants without a background and a context. They did not come out of nowhere as unadulterated and uncaused evil”.

Thus Lo argues, that to claim that the latest terror attacks were “unprovoked” is to whitewash the background and context that constitute the very history of this unending conflict in Palestine.

US media’s ‘morally reprehensible propaganda’

“It’s morally reprehensible propaganda of the worst kind that the mainstream Anglo-American media culture has been guilty of for decades,” he says.

“But the real problem with that is not only with morality but also with the very practical politics of searching for a viable peace settlement”.

He is concerned that “with their unconditional and uncritical support of Israel, the West and the United States in particular have essentially made such a peace impossible”.

Writing in India’s Hindu newspaper, Denmark-based Indian professor of literature Dr Tabish Khair points out that historically, Palestinians have had to indulge in drastic and violent acts to draw attention to their plight and the oppressive policies of Israel.

“The Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), under Yasser Arafat’s leadership, used such ‘terrorist’ acts to focus world attention on the Palestinian problem, and without such actions, the West would have looked the other way while the Palestinians were slowly airbrushed out of history,” he argues.

While the PLO fought a secular Palestinian battle for nationhood, which was largely ignored by Western powers, this lead to political Islam’s development in the later part of the 1970s, and Hamas is a product of that.

“Today, we live in a world where political Islam is associated almost entirely with Islam — and almost all Muslims,” he notes.

Palestinian cause still resonates

But, the Palestinian cause still resonates beyond the Muslim communities, as the reactions in Asia reflect.

Indian historian and journalist Vijay Prashad, writing in Bangladesh’s Daily Star, notes the savagery of the impending war against the Palestinian people will be noted by the global community.

He points out that Hamas was never allowed to function as a voice for the Palestinian people, even after they won a landslide democratic election in Gaza in January 2006.

“The victory of Hamas was condemned by the Israelis and the West, who decided to use armed force to overthrow the election result,” he points out.

“Gaza was never allowed a political process, in fact never allowed to shape any kind of political authority to speak for the people”.

Prashad points out that when the Palestinians conducted a non-violent march in 2019 for their rights to nationhood, they were met with Israeli bombs that killed 200 people.

“When non-violent protest is met with force, it becomes difficult to convince people to remain on that path and not take up arms,” he argues.

Prashad disputes the Western media’s argument that Israel has a “right to defend itself” because the Palestinians are people under occupation. Under the Geneva Convention, Israel has an obligation to protect them.

Under the Geneva Convention, Prashad argues that the Israeli government’s “collective punishment” strategy is a war crime.

“The International Criminal Court opened an investigation into Israeli war crimes in 2021 but it was not able to move forward even to collect information”.

Kalinga Seneviratne is a correspondent for IDN-InDepthNews, the flagship agency of the non-profit International Press Syndicate (IPS). Republished under a Creative Commons licence.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz