Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Mohan Singh, Professor of Agri-Food Biotechnology, School of Agriculture, Food and Ecosystem Sciences at the University of Melbourne., The University of Melbourne

Australia’s vital agriculture sector will be hit hard by steadily rising global temperatures. Our climate is already prone to droughts and floods. Climate change is expected to supercharge this, causing sudden flash droughts, changing rainfall patterns and intense flooding rains. Farm profits fell 23% in the 20 years to 2020, and the trend is expected to continue.

Unchecked, climate change will make it harder to produce food on a large scale. We get over 40% of our calories from just three plants: wheat, rice and corn. Climate change poses very real risks to these plants, with recent research suggesting the potential for synchronised crop failures.

While we have long modified our crops to repel pests or increase yields, until now, no commercial crop has been designed to tolerate heat. We are working on this problem by trying to make soybean plants able to tolerate the extreme weather of a hotter world.

What threat does climate change pose to our food?

By 2050, food production must increase by 60% in order to feed the 9.8 billion people projected to be on the planet, according to UN Food and Agriculture Organization estimates.

Every 1°C increase in temperature during cropping seasons is linked to a 10% drop in rice yield. A temperature rise of 1°C could lead to a 6.4% drop in wheat yields worldwide. That’s as if we took a major crop exporter like Ukraine (6% of traded crops before the war) out of the equation.

Plants, unlike animals, cannot seek refuge from heat. The only solution is to make them better able to tolerate what is to come.

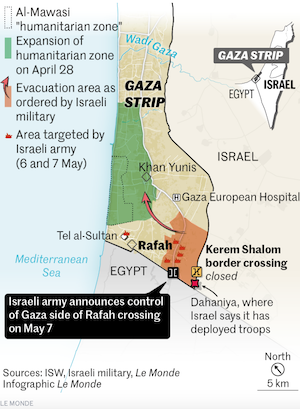

These events are already arriving. In April 2022, farmers in India’s Punjab state lost over half of their wheat harvest to a scorching heatwave. This month, scorching temperatures in Southeast Asia are savaging crops.

What happens to plants when they face extreme heat?

Plants use photosynthesis to convert sunlight and carbon dioxide into sugary food. When it’s too hot, this process gets harder.

More heat forces plants to evaporate water to cool themselves. If a plant loses too much water, its leaves wilt and its growth stalls. A plant’s solar panels – the leaves – cannot capture sunlight when wilted. No water, no energy to make the fruit or grain we want to eat. When the air temperature hits 50°C, photosynthesis shuts down.

Hotter temperatures can make it harder for plants to produce pollen and seeds, and can make it flower earlier. Heat weakens a plant, leaving it more vulnerable to pests and diseases.

Brita Seifert/Shutterstock

Our seed crops – from rice to wheat to soybeans – rely on sexual reproduction. The plants have to be fertilised (pollinated by bees and flies, for instance) to produce a good yield.

If a heatwave strikes during the fertilisation period, plants find it harder to set their seeds and the farmer’s yield drops. Worse, high temperatures cause sterile pollen, which slashes the number of seeds a plant can produce. Pollinators such as bees are also finding it hard to adapt to the heat.

Read more:

Exposing plants to an unusual chemical early on may bolster their growth and help feed the world

Preparing our crops

To give our crops the best chance, we will have to use genetic modification techniques. While these have often been controversial, they are our best shot in responding to the threat.

The reason is genetic modification gives us more precise control over a plant’s genome than the traditional method of breeding for specific traits. It’s also much faster as we can isolate genes from one organism and transfer it to another without sexual reproduction. So while we can’t cross sunflowers with wheat using sexual reproduction, we can take sunflower genes and transfer them to wheat.

For decades, we’ve relied on genetically modified versions of some of our most important food and fibre crops. Nearly 80% of soybeans worldwide have been genetically modified to boost yield and make them more nutritious. Genetically modified canola accounts for more than 90% of production in Canada and the United States, while about 20% of the canola grown in Australia is genetically modified. But until now, we’ve had no commercially adopted crops modified to resist heat.

One way to do this is to search for heat tolerant plants and transfer their prowess to our crops. Some plants are remarkably heat tolerant, such as the living fossil welwitschia mirabilis, which can survive in the Namibian desert with almost zero rainfall.

Heat shock and heat sensors

Plant cells possess heat-shock proteins, just as ours do. These help plants survive heat by protecting the protein-folding process in other proteins. If heat-shock proteins weren’t there, vital proteins would unfold rather than fold into the right shape for the job.

We can try to strengthen how these existing heat-shock proteins function, so the cells can keep functioning in hotter conditions.

We can also tweak the behaviour of genes acting as heat sensors. These genes operate as master switches, controlling a cell’s response to heat by summoning protective heat shock proteins and antioxidants.

In our laboratory, we have modified soybean plants by strengthening these heat-sensing master switch genes. Soybean plants expressing higher levels of this gene had significant increases in protection. Under short, intense heatwave conditions, these modified plants wilted less, produced more viable pollen, had fewer structural deformities, and had better yields under heat stress conditions.

Kikujiarm/Shutterstock

What about wheat?

While we have become accustomed to genetically modified soybeans, we have not yet come to terms with the need to alter wheat – the single most important staple crop.

Heatwaves pose a similar problem for wheat, but community acceptance is not there. The pushback against modified wheat has been very strong.

In the lab, researchers in universities and agricultural companies have had success in modifying wheat to tolerate more heat. But none of these changes have made it into crops planted in fields.

If we are to feed a growing population on a hotter planet, this will have to change.

![]()

The research in Mohan Singh’s laboratory has been funded by the Australian Research Council (ARC) over the years. In addition, the University of Melbourne provided funding for the research.

Prem Bhalla had received funding from the Australian Research Council and the University of Melbourne.

– ref. Heat is coming for our crops. We have to make them ready – https://theconversation.com/heat-is-coming-for-our-crops-we-have-to-make-them-ready-223553