Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Garry Jennings, Professor of Medicine, University of Sydney

Nobody dies in good health, at least in their final moments. But to think the causes of death are easy to count or that there is generally a single reason somebody passes is an oversimplification.

In fact, in 2022, four out of five Australians had multiple conditions at the time of death listed on their death certificate, and almost one-quarter had five or more recorded. This is one of many key findings from a new report from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW).

The report distinguishes between three types of causes of death – underlying, direct, and contributory. An underlying cause is the condition that initiates the chain of events leading to death, such as having coronary heart disease. The direct cause of death is what the person died from (rather than with), like a heart attack. Contributory causes are things that significantly contributed to the chain of events leading to death but are not directly involved, like having high blood pressure. The report also tracks how these three types of causes can overlap in deaths involving multiple causes.

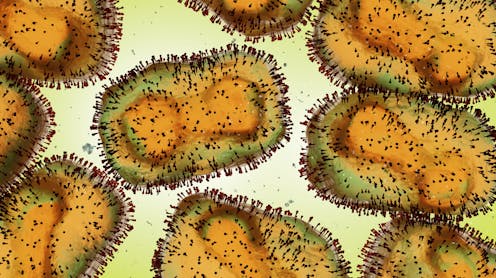

In 2022 the top five conditions involved in deaths in Australia were coronary heart disease (20% of deaths), dementia (18%), hypertension, or high blood pressure (12%), cerebrovascular disease such as stroke (11.5%), and diabetes (11.4%).

When the underlying cause of death was examined, the list was similar (coronary heart disease 10%, dementia 9%, cerebrovascular disease 5%, followed by COVID and lung cancer, each 5%). This means coronary heart disease was not just lurking at the time of death but also the major underlying cause.

The direct cause of death however was most often a lower respiratory condition (8%), cardiac or respiratory arrest (6.5%), sepsis (6%), pneumonitis, or lung inflammation (4%) or hypertension (4%).

Why is this important?

Without looking at all the contributing causes of death, the role of important factors such as coronary heart disease, sepsis, depression, high blood pressure and alcohol use can be underestimated.

Even more importantly, the various causes draw attention to the areas where we should be focusing public health prevention. The report also helps us understand which groups to focus on for prevention and health care. For example, the number one cause of death in women was dementia, whereas in men it was coronary heart disease.

People aged under 55 tended to die from external events such as accidents and violence, whereas older people died against a background of chronic disease.

We cannot prevent death, but we can prevent many diseases and injuries. And this report highlights that many of these causes of death, both for younger Australians and older, are preventable. The top five conditions involved in death (coronary heart disease, dementia, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease and diabetes) all share common risk factors such as tobacco use, high cholesterol, poor nutrition, physical inactivity, or are risk factors themselves, like hypertension or diabetes.

Tobacco use, high blood pressure, being overweight or obese and poor diet were attributable to a combined 44% of all deaths in this report. This suggests a comprehensive approach to health promotion, disease prevention and management is needed.

This should include strategies and programs encouraging eating a healthy diet, participating in regular physical activity, limiting or eliminating alcohol consumption, quitting smoking, and seeing a doctor for regular health screenings, such as the Medicare-funded Heart Health Checks. Programs directed at accident prevention, mental health and violence, especially gender-related violence, will address untimely deaths in the young.

![]()

Garry Jennings receives funding from the National Heart Foundation and The American Heart Association.

– ref. 1 in 5 deaths are caused by heart disease, but what else are Australians dying from? – tag:theconversation.com,2011:article/231598