Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Brendan Wintle, Professor in Conservation Science, School of Ecosystem and Forest Science, The University of Melbourne

Earth is facing a human-driven climate crisis, which demands a rapid transition to low-carbon energy sources such as wind and solar power. But we’re also living through a mass extinction event. Never before in human history have there been such high such rates of species loss and ecosystem collapse.

The biodiversity crisis is not just distressing, it’s a major threat to the global economy. More than half of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) directly depends on nature. The World Economic Forum rates biodiversity loss in the top risks to the global economy over the next decade, after climate change and natural disasters.

Human-driven climate change damages nature – and loss of nature exacerbates climate change. So if humanity’s efforts to mitigate climate change end up damaging nature, we shoot ourselves in the foot.

Australia, however, must face up to an uncomfortable truth: we are putting renewable energy projects in places that damage the species and ecosystems on which we depend.

Steve Nowakowski, Rainforest Reserves Australia

Renewables on the run

Renewable energy projects are being developed that damage nature and culturally significant sites. Others are resented by communities, or fail at regulatory hurdles.

Environmentally damaging projects put another nail in the coffin of species and ecosystems already under immense pressure. Even those that affect a relatively small area contribute to nature’s “death by a thousand cuts”.

Take, for example, the proposed Euston wind farm in southwest New South Wales. It would entail 96 turbines built near the Willandra Lakes World Heritage area, potentially affecting threatened birds.

And in North Queensland, the Upper Burdekin wind farm proposal will remove 769 hectares of endangered species habitat relied on by Sharman’s wallabies, koalas and northern greater gliders. The cleared area would be almost 200 times bigger than the Melbourne Cricket Ground.

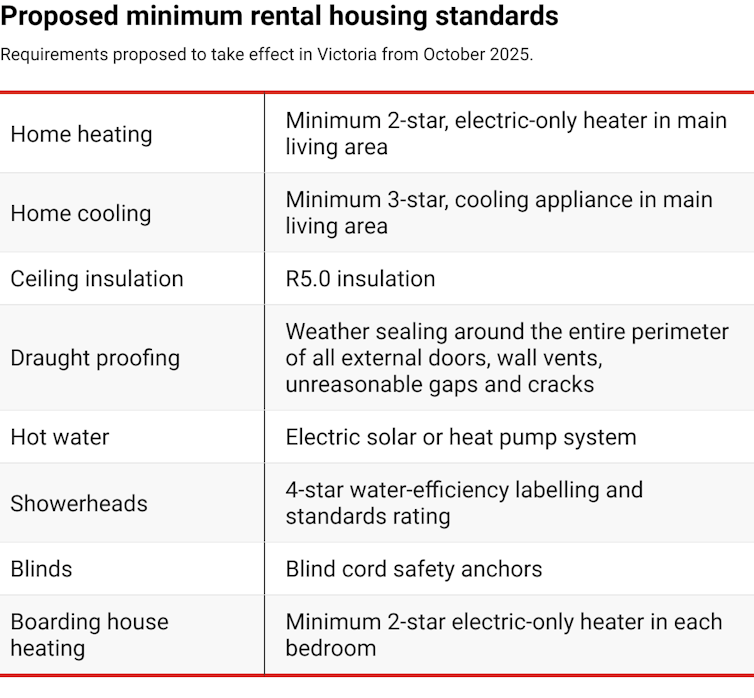

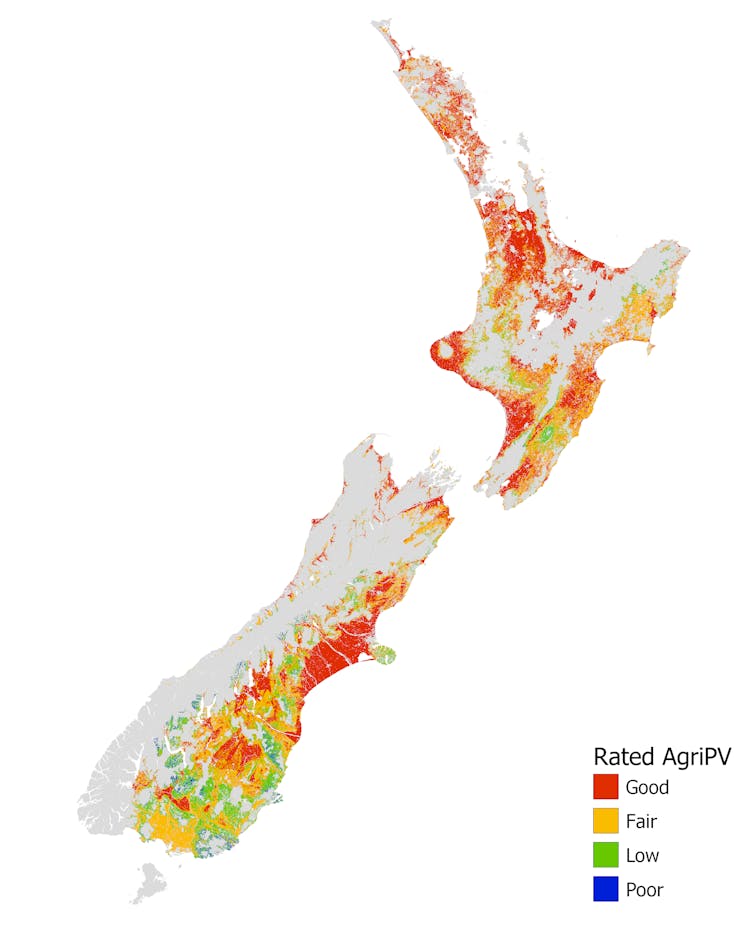

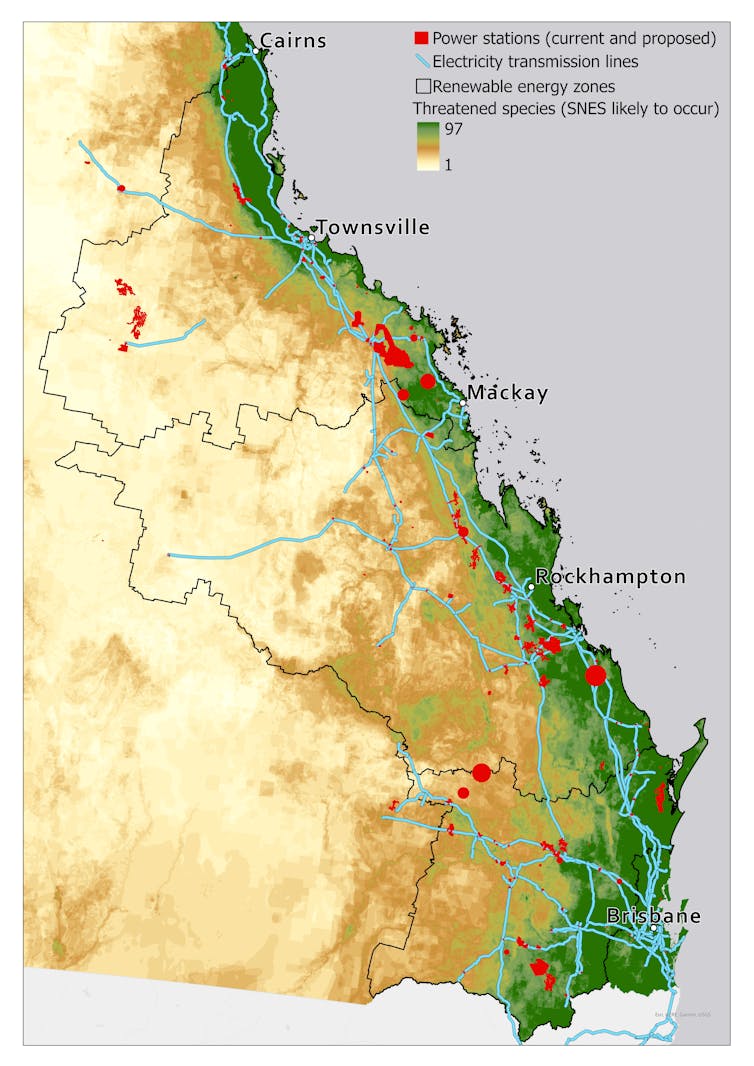

The simple overlay below, which we prepared, illustrates the problem in Queensland. The analysis, part of a research project funded by Boundless Earth, shows in stark detail the crossover between energy projects, transmission lines and nationally listed threatened species habitats and ecosystems.

Source: Authors

The ‘fast-track’ can also be the good track

In their understandable haste to get more clean energy projects built, state and federal governments are promising to “streamline” approvals processes. Fast-tracked approvals will only provide net social benefit if they are based on good data, sound analysis and genuine community engagement.

Two successive reviews of our national environmental laws, most recently by Graeme Samuel, identified what’s needed to improve the efficiency of development approvals and get better outcomes for nature. The answer? Good planning at the regional scale, underpinned by good data.

At a minimum, we need to know the locations of threatened or culturally significant species and places, high-value agriculture and valuable natural areas. A proposed new federal body, Environmental Information Australia, would seek to centralise existing biodiversity data. But significantly more data are required to fill important knowledge gaps.

Good planning can create shared purpose and bring positive environmental and social outcomes, including certainty to developers and conservationists. In Queensland, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park has enjoyed strong planning support based on good data and high community participation for more than 30 years, with some conservation success.

In contrast, poor planning polarises stakeholders and communities. It erodes trust between stakeholders, developers and government by reducing the integrity and quality of planning decisions. This leads to ongoing conflict over land use, as has been observed in Queensland.

A proposal to build a renewable energy microgrid in Queensland’s Daintree rainforest is a case in point. It is causing pain for local communities, pitting renewable energy advocates against conservation organisations.

When projects fail to gain community support and necessary approvals, the proponent’s money is wasted, and we lose precious time in the urgent transition to renewables.

Renewables projects should enhance nature

It’s surprising and disappointing how few proponents of Australian renewables projects actively seek to enhance the habitat values of the land their projects occupy.

In part, this is because planning regulations are still firmly focused on avoiding impacts to nature, and offsetting damage when it occurs.

Instead, we need policies and laws that compel nature-positive approaches that regenerate biodiversity.

In California, for example, a test project to grow native plants under solar panels is restoring prairie land and pollinator habitat at the site of a decommissioned nuclear power station. In Australia, there are occasional signs we may move in a similar direction.

It’s not hard to envisage a renewables rollout that prioritises projects on degraded, ex-agricultural land, avoiding damage to critical habitats and benefiting nature. Wind turbines should be built away from natural vegetation and migratory routes for birds and bats.

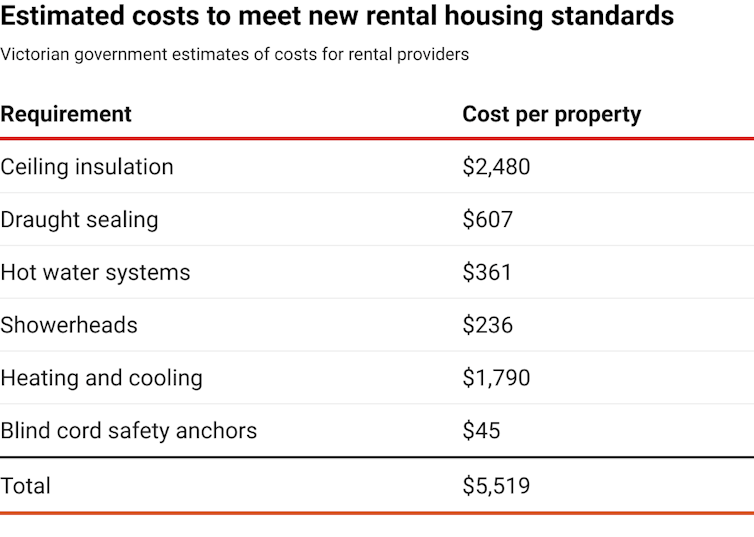

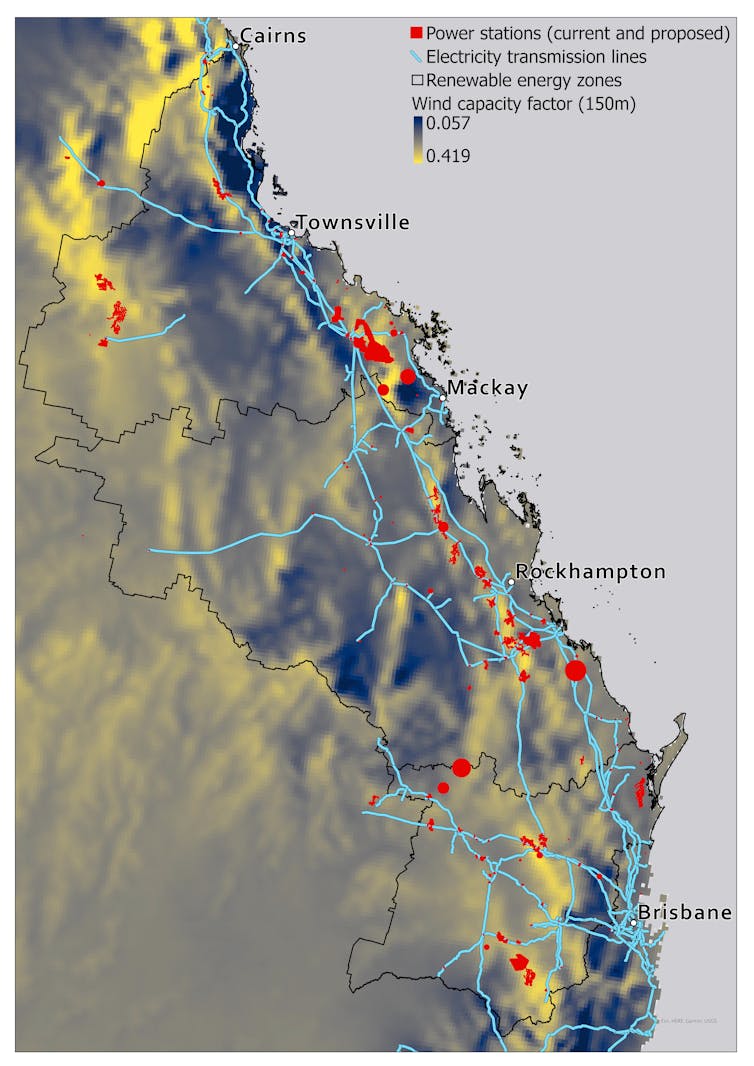

Our mapping for potential wind and solar projects in southern Queensland shows strong potential west of the Great Dividing Range for energy generation without the same level of land-use conflict with natural values and productive agriculture.

Authors with source data from Geoscience Australia: https://ecat.ga.gov.au/geonetwork/srv/api/records/0b2f1c73-0358-4ff0-9572-2d1ab5077566

A major challenge to energy project development in Queensland, as in some other parts of Australia, is a lack of transmission infrastructure, or “poles and wires”, in the places where renewable energy and nature could most happily coexist. This infrastructure should urgently be developed in a way that does not impact natural vegetation and species habitats.

Rapidly reaching net zero is not negotiable to avoiding the worst ravages of climate change. But doing so in a way that damages nature is self-defeating. We have the planning tools and data needed to create a nature-positive climate transition. Now we need adequate state and Commonwealth government investment, leadership and political will.

![]()

Brendan Wintle has received funding from The Australian Research Council, the Victorian State Government, the NSW State Government, the Queensland State Government, the Commonwealth National Environmental Science Program, the Ian Potter Foundation, the Hermon Slade Foundation, Boundless Earth Foundation and the Australian Conservation Foundation. Wintle is a Board Director of Zoos Victoria and a lead councillor of the Biodiversity Council. Thanks to Jaana Dielenberg for contribution to this article.

James Watson has received funding from the Australian Research Council, National Environmental Science Program, South Australia’s Department of Environment and Water as well as from Bush Heritage Australia, Queensland Conservation Council, Australian Conservation Foundation, The Wildnerness Society and Birdlife Australia. He serves on scientific committees for Subak Australia and BirdLife Australia and has a long-term scientific relationship with Bush Heritage Australia and Wildlife Conservation Society. He serves on the Queensland Government’s Land Restoration Fund’s Investment Panel as the Deputy Chair.

Michelle Ward has received funding from The Australian Research Council and the Commonwealth National Environmental Science Program. She was Science and Research Lead at WWF-Australia and is currently on a Technical Advisory Panel for a project run by the Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists.

Sarah Bekessy receives funding from the Australian Research Council, the National Health and Medical Research Council, the Ian Potter Foundation and the European Commission. She is a lead councillor of the Biodiversity Council, a board member of Bush Heritage Australia, a member of WWF’s Eminent Scientists Group, a member of the Advisory Group for Wood for Good and a member of the Technical Working Group of the Living Future Institute of Australia.

Andrew Rogers does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. A renewable energy transition that doesn’t harm nature? It’s not just possible, it’s essential – tag:theconversation.com,2011:article/229605