Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Ben McCann, Associate Professor of French Studies, University of Adelaide

What might be the most seismic moment in American cinema? Film “speaking” for the first time in The Jazz Singer? Dorothy entering the Land of Oz? That menacing shark that in 1975 invented the summer blockbuster?

Or how about that moment when two hitmen on their way to a job began talking about the intricacies of European fast food while listening to Kool & The Gang?

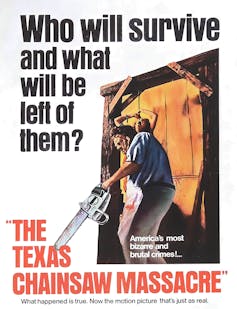

Directed by Quentin Tarantino, Pulp Fiction (1994) celebrates its 30th birthday this month. Watching it now, this story of a motley crew of mobsters, drug dealers and lowlifes in sunny Los Angeles still feels startlingly new.

Widely regarded as Tarantino’s masterpiece, the director’s dazzling second film was considered era-defining for its memorable dialogue, innovative narrative structure and unique blend of humour and violence. It was nominated for seven Academy Awards, made stars of Samuel L. Jackson and Uma Thurman, and revitalised John Travolta’s career.

Pulp Fiction is dark, often poignant, and very funny. It is, as one critic describes it, an “intravenous jab of callous madness, black comedy and strange unwholesome euphoria”.

IMDB

A Möbius strip plot

Famous for its non-linear narrative, Pulp Fiction weaves together a trio of connected crime stories. The three chapters – Vincent Vega and Marsellus Wallace’s Wife, The Gold Watch and The Bonnie Situation – loop, twist and intersect but, crucially, never confuse the viewer.

Tarantino has often paid tribute to French filmmakers Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Melville, whose earlier films also presented their narratives out of chronological order and modified the rules of the crime genre.

By inviting audiences to piece Pulp Fiction together like a puzzle, Tarantino laid the way for subsequent achronological films such as Memento (2000), Go (1999) and Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (1998).

Pop culture meets postmodernism

In his influential essay Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, first published in 1984, political theorist Frederic Jameson coined the term “new depthlessness” to describe postmodern culture.

Jameson perceived a shift away from the depth, meaning and authenticity that characterised earlier forms of culture, towards a focus on surface and style.

IMDB

Pulp Fiction fits Jameson’s definition of depthlessness. It is stuffed with homages to popular culture and a vivid array of character types drawn from other B-movies – hitmen, molls, mob bosses, double-crossing boxers, traumatised war veterans and tuxedo-wearing “fixers”. It is a film of surfaces and allusions.

Jackson, Travolta and Thurman feature alongside established 1990s box-office stars including Bruce Willis and industry stalwarts Harvey Keitel and Christopher Walken, both of whom have brief but memorable cameos.

The film’s most iconic scene takes place at the retro 1950s-themed Jack Rabbit Slim’s diner. Thurman’s twist contest with Travolta fondly echoes Travolta’s earlier dancing in Saturday Night Fever (1977) and pays homage to other dance scenes in films such as 8 ½ (1963) and Band of Outsiders (1964).

Words and music

Film critic Roger Ebert once noted how Tarantino’s characters “often speak at right angles to the action”, giving long speeches before getting on with the job at hand.

Pulp Fiction is full of witty and quotable monologues and dialogue, ranging from the philosophical to the mundane. Conversations about foot massages and blueberry pie bump up against Bible verses and reflections on fate and redemption.

The film’s 1995 Oscar for Best Original Screenplay was a fitting achievement for Tarantino, who many regard as the snappiest writer in film history. Countless other filmmakers have looked to replicate Pulp Fiction’s mashup of cool and coarse.

Needle drops are just as important in establishing Pulp Fiction’s mood and tone. The film’s eclectic soundtrack pings between surf rock, soul and classic rock ‘n’ roll.

The soundtrack peaked at No. 21 on the Billboard 200 in 1994 and stayed in the charts for more than a year.

Dividing the critics

Though it was officially released in October 1994, Pulp Fiction had already made a stir earlier that by winning the prestigious Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival.

Many expected Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Three Colours: Red to take the top prize. Tarantino himself seemed stunned, telling the Cannes audience: “I don’t make the kind of movies that bring people together. I make movies that split people apart.”

The film has divided critics ever since.

Many adored Pulp Fiction for its intoxicating allure and sheer adrenaline-fuelled pleasure. To this day it maintains a 92% critic score on Rotten Tomatoes. Film critic Todd McCarthy called it a film “bulging with boldness, humour and diabolical invention”.

But the backlash was equally robust. Some criticised the film for its excessive gore and irresponsible use of racial slurs. Screenwriting guru Syd Field felt it was too shallow and too talky. Jean-Luc Godard, once one of Tarantino’s idol, apparently hated it.

Nonetheless, its financial success (a box office return of US$213 million from an $8 million budget) signalled the growing importance and cultural prestige of independent US films. Miramax, the studio that backed it, went on to become a major force in the industry.

IMDB

A lasting legacy

Shortly after Pulp Fiction’s release, the word “Tarantinoesque” appeared in the Oxofrd English Dictionary. The entry reads:

Resembling or imitative of the films of Quentin Tarantino; characteristic or reminiscent of these films Tarantino’s films are typically characterised by graphic and stylized violence, non-linear storylines, cineliterate references, satirical themes, and sharp dialogue.

Pulp Fiction has since been parodied and knocked off countless times. Hollywood suddenly began mass-producing low-budget crime thrillers with witty, self-reflexive dialogue. Things to Do in Denver When You’re Dead (1995), 2 Days In The Valley (1996) and Very Bad Things (1998) are just some example.

Graffiti artist Bansky even stencilled the likeness of Jules and Vincent all over London, with bananas in place of guns. The Simpsons got in on the act too.

Tarantino once summed up his working method as follows:

Ultimately all I’m trying to do is merge sophisticated storytelling with lurid subject matter. I reckon that makes for an entertaining night at the movies.

I’d say there’s no better way to describe Pulp Fiction.

Ben McCann does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. 30 years ago, Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction shook Hollywood and redefined ‘cool’ cinema – https://theconversation.com/30-years-ago-tarantinos-pulp-fiction-shook-hollywood-and-redefined-cool-cinema-236877