Source: Council on Hemispheric Affairs – Analysis-Reportage

St. Lucia during and post Hurricane Beryl

by Tamanisha J. John

Toronto, Ontario

Whenever a hurricane hits in the Caribbean, people rush to point out that it is an indicator of “disaster capitalism” and/or that “disaster capitalism” will surely come. While I agree that non-governmental organizations (NGO) and other organizations profit from disasters in the Caribbean region, and have a long history of doing so, I am less inclined to believe that “disaster capitalism” exists there unless one takes an ahistorical view. Disaster capitalism in the Caribbean can only exist in those states whose revolutions have been defeated and/or undermined, but overall, there has been no massive structural changes in these states. The region is already, and historically has been, ultra-accommodating to capitalism. Disaster capitalism refers to “the use of the shock of disastrous situations to dismantle state participation in the economy and to implant structural changes in the form of laissez-faire capitalism” (Schwartz, 2015, p. 311). To claim that disaster capitalism will come to the Caribbean region would thus indicate a marked period of state participation in the Caribbean that provided for the peoples living there.

Instead, all states’ independence was marked by US interventions given the ideological and economic struggle of the Cold War and the neoliberal turn, which attacked state input and intervention in the market. Caribbean states’ independence was marked by debt and lack of access to capital. It occurred alongside financial institutions’ proliferation of structural adjustment policies whose implementation was necessitated for states in the region to acquire access to loaned capital (John, 2023). Though struggles for nationalizations did occur – in industries like mining, banking, insurance, and others – harsh retaliations from the US and Canada made them unsustainable (John, 2023, p. 134) – with no real reductions in foreign ownership “despite the changes in legal forms of ownership” (Thomas, 1984, p. 168-9). Thus, large foreign ownership of resource extractive industries and financial institutions remained a feature of Caribbean societies when they became independent – just as it also marked the colonial landscape in these spaces. The foreign players that controlled corporations, land, and industries in these countries did change somewhat, but this was also typical with imperial rivalries (Caribbean states themselves having been subject to multiple phases of European colonization throughout their histories).

It was Walter Rodney, who in his 1972 text How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, put forward a critique of the thesis that capitalism had to develop prior to ushering in socialism – which was Marx’s estimation – given that this thesis went against the trajectory of capitalist development in both the Caribbean and in Africa, where the capitalist logics of extraction with disregard for these societies left them in almost permanent states of underdevelopment, that only physical and ideological anti-imperialism could rectify. One of the consequences of this underdevelopment, I argue, is the lack of hurricane preparedness. The logic of “getting people back to work” and “security” in these colonized spaces have always trumped wellbeing for the people and environment – precisely because the people in them have always been categorized as disposable, while the natural resources have been reduced to instruments for the generation of profit. This ideology was true under European empires, and now true under US hegemony in the region – where foreign imposing actors continue to have more say on preparedness, wealth distribution, land ownership, security, economic development, and entrepreneurship (innovation).

In a Region Prone to Hurricanes, Unpreparedness is an Ideological Policy Choice

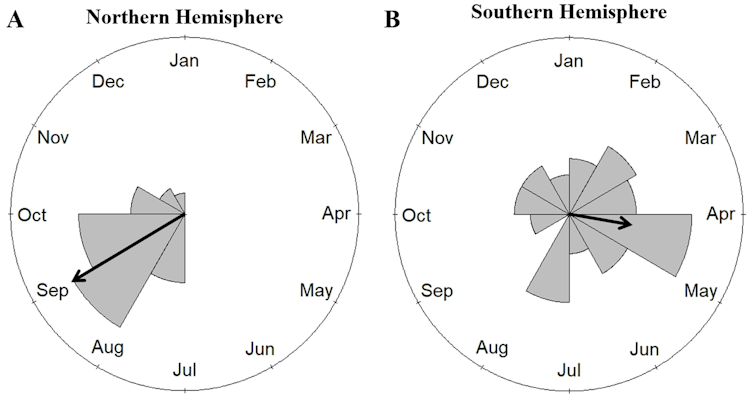

“Hurricanes are not random phenomena. Atmospheric conditions and physics limit their movement” (Schwartz, 2015, p. xvi). In the Caribbean, the Yucatán Peninsula, the Gulf of Mexico, and the South-Eastern United States, we have come to expect a lack of preparedness whenever hurricanes strike. Though Hurricane Beryl’s strength and early formation in June was unprecedented for the Caribbean’s hurricane season, what is precedent is the lack of regional preparedness for hurricanes in a region prone to have them – no matter when these hurricanes form. Forming around June 25th it was clear that Beryl would break the record for earliest formed Category 5 hurricane by the time that it made way into the Caribbean. This was due to the unusually warm temperatures registered in both the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea as early as March, various heatwave advisories and warnings were placed on the region acknowledging that the summer 2024 would be “hotter than usual” (Loop News 2024). When news of Beryl’s formation first spread, people expected the worst given unusually hot increases in temperatures (+4°c) for the region so early in the year.

Making landfall as a Category 4 hurricane in one of the smaller islands of Grenada, Carriacou, on July 1st Beryl would destroy 95% of the infrastructure there before strengthening to a Category 5 hurricane. It would bring even worse devastation to a smaller island of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Mayreu, where reports proclaim that island to have nearly been “erased from the map” (AP News 2024). In its Caribbean path, Beryl brought devastation as a Category 5 and 4 storm to Grenada, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Dominica, Tobago and northern Venezuela, Barbados, and the southern portion of Jamaica. In its North American path, Beryl brought devastation as a Category 2 and 1 storm to Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, before making landfall in Texas and Louisiana. Thereafter the storm was experienced elsewhere in the form of a tropical cyclone and massive downpours of rain. Beryl eventually tapered off in Canada on July 11th where it left heavy rain that caused massive flooding (due to Canada’s neglected flood systems). Beryl’s death toll currently stands at 33, with the storm causing 6 deaths “in Venezuela, 1 in Grenada, 2 in Carriacou, 6 in St. Vincent and the Grenadines, 4 in Jamaica […] at least 11 in the Greater Houston area, 1 in Louisiana, and 2 in Vermont.” (TT Weather Center 2024)”

Now that the storm has passed, people in impacted areas must contend with the loss of life, destruction of physical infrastructure – including homes and businesses, the lack of food and other basic products, as well as the lack of power and electricity. While contending with loss, victims of this severe weather will start to question the inability of their governments – rich or poor – to adequately address the post hurricane scenarios that they find themselves in repeatedly. This discontent with unpreparedness is now prevalent even before the hurricane season itself has ended.

A Note on Cuba’s Hurricane Preparedness, The Importance of Ideology

One of the most infuriating elements of hurricanes in this region is the “disaster” narratives that come after them, which falsely assert the “naturalness” of unpreparedness given the chaos of the disaster itself – when unpreparedness is, in fact, an ideological policy choice. Poorer states in this region are shackled by an unwillingness of the state to drastically deviate from “larger institutional constraints from which the logic of colonial administration derived its central purpose” and are inherited (Pérez Jr., 2001, p. 133-4). On the other hand, richer states are shackled by their individualist ideologies which offer “vigorous critiques of government expenditure” which leave preparedness up to “market-driven, neoliberal economic policies,” that turn state and local responsibilities over “to charitable institutions, to churches, or to the victims themselves and their communities” (Schwartz, 2015, p. 300).

When looking at states in the Western Hemisphere which frequently experience hurricanes, Cuba stands out as a state which tends to fare better in the post hurricane environment given that state’s policies of shared responsibility towards its people. This even as Cuba has been subjected to a draining embargo and sanctions which places a burden on economic growth there. Yet still, Washington maintains that Cuba’s successful hurricane response and disaster mitigation strategies amount to “the exchange of liberty for effectiveness” (Schwartz, 2015, p. 293-4). Though couched in this language of ‘liberty,’ mitigating the loss of life ensures one’s longtime enjoyment of liberty – as opposed to dying for ‘liberty’s’ sake during a hurricane (or other disasters like the COVID-19 pandemic). For example, Cuba’s hurricane preparedness in relation to the US stands out. Cuba’s disaster response compares a bit more favorably to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). FEMA “oversaw 15 times more deaths from hurricanes than Cuba from 2005 — the year that Katrina struck New Orleans — to 2015” (Wolfe, 2021).

This is because Cuba’s disaster preparedness is proactive, prioritizing human life and well-being given the ideological foundations of its revolution that transformed political, social, economic, and environmental relations in the country. US disaster preparedness on the other hand prioritizes profit at the expense of people – it is reactionary and reactive, often blaming victims of hurricane disasters for the lack of state preparedness.

The Caribbean Hurricane as Natural Phenomena, the Disaster as Colonial Inheritance

Hurricanes are not experienced equally amongst states in the Western Hemisphere. People living on Caribbean islands tend to experience the worst effects of hurricanes when they do strike, and it is also people on these same islands which tend to have less resources to recover from the impacts of a hurricane. Though Cuba’s hurricane preparedness is commendable, infrastructure and livelihoods there are still devastated by hurricanes. Many of the Caribbean islands are geographically located “in the Atlantic Hurricane Alley, [and] the region is sensitive to large-scale fluctuation of ocean patterns that are disrupted by warming seas” (Zodgekar, et. al 2023, p. 321). Additionally, populations and infrastructure on these islands tend to be concentrated on the coast – a colonial holdover – given that European “settlements were established directly in the path of oncoming hurricanes (Pérez Jr., 2001, p. 8). Initially due to lack of knowledge, this trend remained unchanged amongst Europeans given the need to export what was being extracted from these islands using the ports developed on the coasts.

Historically, environmental disasters (hurricanes, earthquakes, and droughts) throughout the 1600s-1900s would consolidate land amongst the wealthiest European settlers on different islands and would foil settler attempts to diversify agriculture on islands. This was because wealthy settlers could more easily recover and rebuild what was lost in the aftermath of a hurricane, due to their ability to access credit from Europe and resort to using their own fortunes (wealth and networks). On the other hand, smaller settlers unable to rebuild and recover from hurricane losses had a harder time accessing credit – and creditors within Europe viewed loaning to smaller settlers as a financial burden. If these smaller settlers were already in debt, the passing of a hurricane meant that they would either have to work off debt by giving all that they had to a creditor in Europe, or one on the island, by entering into a credit arrangement with a wealthier plantation owner (Mulcahy, 2006, p. 86-8). These losses were quite frequent, as it is known that these phenomena made it so that some European creditors in Europe would amass plantation wealth, even if they themselves had never visited a Caribbean island or formally engaged in plantation life (Mulcahy, 2006, p. 87-8).

These dynamics, in part, explain the predominance of the cultivation of sugar (and rice in what would become the South-Eastern United States) within the region, and even then, “plantership […] necessitated deep pockets (or strong credit) to survive its constant and rapid fluctuations” (Mulcahy, 2006, p. 66). “Without access to credit, smaller farmers were forced to sell their lands to wealthier and more secure planters, who thereby expanded their landholdings and production capabilities” (Mulcahy, 2006, p. 86). This consolidation of larger and wealthier plantations also made other concerns arise, namely the depopulation of settlers from the islands, as debtors opted to leave in the aftermath of storms, and later the transfers of estates to owners outside of the colonies (Mulcahy, 2006, p. 86-7). In essence, settlers’ decision to flee in the wake of, or after, a hurricane shaped population dynamics and demographics in colonies. They also shaped the lack of hurricane preparedness in colonies. Wealthier planters on the islands, and Europeans in Europe, who could suffer from hurricane losses (hurricanes themselves not being guaranteed every season), rebuild afterwards, and recover previous losses given the profit from plantation trade goods – had less incentives to plan ahead if they were not as risk of losing everything they had amassed in their life after a hurricane.

In smaller island states’, where plantation systems were heavily disrupted or stunted in growth due to geography of the land (especially in the Lesser Antilles), even fewer attempts were made to develop any infrastructure which could protect against storms (Mulcahy, 2006). To be clear, this does not mean that these landscapes were spared from destruction which made the impacts of hurricanes worse: deforestation, overgrazing, and over-cultivation of Caribbean islands during centuries of European colonialism that included dispossession of indigenous groups and the enslavement of Africans, also impacted how hurricanes came to be experienced. While planter consolidation, rebuilding, and profits have so far been underscored here – the elephant in the room is that all of this occurred alongside the massive death toll of enslaved Africans who suffered the most both during and after the passage of a hurricane. Outside of the high death tolls for enslaved Africans on the islands, once a hurricane passed, the ultimate goal in the colonies became the reestablishment of ‘law-and-order’ given fears of slave revolt in the wake of destruction (Mulcahy, 2006; Schwartz, 2015). Although slave-revolts post hurricane remained a consistent fear of settlers, slave revolts did not occur after a hurricane due to its disproportionate toll on enslaved populations who were “often the most debilitated by the shortage of food and the diseases that followed the hurricane” (Schwartz, 2015, p. 49).

Caribbean Indigenous Peoples Blamed European Imperial Settlement for Increased Hurricane Devastation

From historical accounts, we know that the Spaniards were the first Europeans to experience a hurricane within the Western Hemisphere during Columbus’s second voyage in 1494/5 (Pérez Jr., 2001; Mulcahy, 2006; Schwartz, 2015). The hurricane experience was unlike anything that Europeans had observed in Europe, and it was from this experience that they sought out intel from the indigenous peoples in the Caribbean. For Caribbean indigenous peoples, “the great storms were part of the annual cycle of life. They respected their power and often deified it, but they also sought practical ways to adjust their lives to the storms. Examples were many: The Calusas of southwest Florida planted rows of trees to serve as windbreaks to protect their villages from hurricanes. On the islands of the Greater Antilles—Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico—the Taino people preferred root crops like yucca, malanga, and yautia because of their resistance to windstorm damage. The Maya of Yucatan generally avoided building their cities on the coast because they understood that such locations were vulnerable to the winds and to ocean surges that accompanied the storms” (Schwartz, 2015, p. 5). Further, Indigenous representations of hurricanes were overall accurate and are similar to modern meteorological mapping of these storms. Europeans also learned from Caribbean Indigenous groups that you could “track” when a hurricane would strike. These developments meant that Indigenous Caribbean knowledge of the hurricane was not only limited to the occurrence of storm, but also meant that Indigenous Caribbean societies factored in preparedness for hurricanes within their worldviews.

Given Caribbean Indigenous knowledge of hurricanes, it is these same people who also recognized that the changes to the landscape by European colonialism contributed to the increased devastation caused by hurricanes between the 1600s-1900s. As such, English colonists who would also come to experience the hurricanes report that “several elderly Caribs stated that hurricanes had become more frequent in recent years, which they viewed as a punishment for their interactions with Europeans” and the main “alteration that our people attribute the more frequent happenings of Hurricanes” (Mulcahy, 2006, p. 35). What these settler accounts reveal about Indigenous Caribbean peoples is what Schwartz notes in his 2015 book, Sea of Storms: A History of Hurricanes in the Greater Caribbean from Columbus to Katrina, that although “hurricanes were a natural phenomenon; what made them disasters was the patterns of settlement, economic activity, and other human action” (p. 74). Nonetheless, colonial ecological and environmental destruction in the Caribbean – which increased the felt impact of hurricanes – remained worthwhile for Europeans given the high profits to be made from export crops, which kept people there to rebuild after hurricanes. Mulcahy in his 2006 book, Hurricanes and Society in the British Greater Caribbean, 1624 – 1783, writes “European settlers and colonists were engaged in a never-ending struggle against nature in their quest for wealth” (p. 93)

Additionally, the European empire’s responses to hurricanes also influenced decisions to stay. Because colonial societies in the Caribbean were stratified along racial and other social hierarchies – hurricanes presented opportunities for large scale consolidation of plantation property on islands which privileged wealthy plantation owners. Additionally, smaller merchants and plantations which could not recover post hurricane were sometimes forced to transfer ownership to merchants in Europe – who never had to visit these properties while amassing wealth from them thereafter (Mulcahy 2006, p. 88). Disaster relief to the colonies thus came to be historically designed as a way for further economic integration, and “assistance to the colonies in times of disaster would bring wealth and affluence to the empire” (Mulcahy 2006, p. 162). Disaster assistance – while increasing inequalities between all peoples in the colonies – did overall benefit imperial capitalism and patriotism within the empire, amongst loyal subjects, especially amongst elite classes, who received the majority of aid based on their losses.

Banking on Hurricanes and Absolving Empire of Responsibility: Debates in Europe

While debates in Europe raged regarding enriching the already wealthy within the colonies with disaster relief – these debates did not change the post-hurricane reality of which those most needing of aid (Indigenous groups, enslaved Africans, indentured workers, small merchants, and small planters) were the least likely to receive it, which was true across all of the different European colonies (Pérez Jr., 2001; Mulcahy, 2006; Schwartz, 2015). “Vulnerability to the hurricane itself was a function of the material determinants” around which colonial social hierarchies were arranged (Pérez Jr., 2001, p. 111). In Europe, debates focused primarily on creditors, so it was argued that the wealthy were more primed to repay creditors when/if they received disaster relief after a hurricane. On the other hand, the proliferation of print news meant that individuals and organizations (e.g., the Church) could send aid to the colonies after disaster struck. Previously, when disaster struck it would take months for news to reach those in Europe, even as the disruptions in trade were more readily felt. Moreover, it was hard for the public in Europe to understand the scale of destruction caused by hurricanes in the Americas, given that this kind of natural disaster did not occur in Europe.

With the establishment of print media, the destruction caused by hurricanes and the damages that they did to plantation systems – which would require a lot of assistance to recover – was made much more readily available to people who could empathize and assist in recovery efforts. Within the British empire, some newspapers even published who would send what amount and type of post disaster relief to the colonies, which undoubtedly contributed to the charitable giving of some wealthy individuals (Mulcahy 2006; Schwartz 2015). Given that the voyage from Europe to the various colonies was long, there was illegal trading between different colonies to provide relief to one another faster – including with the United States, even after the American Revolution.

It is this colonial history which still shapes the lack of hurricane preparedness in a region prone to have them. Thus, most scholars on hurricanes in the region continue to highlight the colonial and slave legacies which have shaped regional unpreparedness to hurricanes. Though the United States is a wealthier country today with the capabilities to develop hurricane preparedness – even if only within its own borders – it is elite US security interests and ideological leanings which have prevented it from doing so. Additionally, historians like Schwartz (2015) make a compelling argument that “the United States, by its military and political expansion into the Caribbean after 1898, its foreign policy objectives in the Cold War, and through its advocacy of certain forms of capitalism joined with its ability to impose its preferences on international institutions, has also influenced the way in which the whole region has faced hurricanes and other disasters” (Schwartz, 2015, p. xviii-xix). This implies that the United States – like the European empire’s past – also has a stake, or interest, in regional hurricane unpreparedness for both political, economic, and security objectives.

US Imperial Extensions in the Caribbean, Impact on Hurricane Preparedness

From this overview of the history of hurricanes in the Caribbean, the Yucatán Peninsula, the Gulf of Mexico, and the South-Eastern United States a few things become clear: hurricane preparedness has never been a concern for colonial capitalist development. Hurricane disasters came to be recognized as extremely ruinous to those occupying the lowest rungs of colonial societies, aid was given to the wealthy people who were understood as being able to put aid to better usage, and disaster situations consolidated preferred modes of accumulation in otherwise “chaotic” and uncivilized landscapes. Thus, outside of patriotic tales and misremembering of the storm events, historically “hopes of communal solidarity” in the wake and aftermath of hurricanes “were either naïve or disingenuous [… with] social divisions ha[ving] always shaped the responses to hurricanes (Schwartz, 2015, p. 68-9). Given strict colonial hierarchies, the maintenance of order – to dissuade slave revolts and looting – were always preeminent concerns of empires and those with wealth and power. This is important to plainly state, given that little has changed in today’s experience with hurricanes in the region.

Today’s granting of conditioned relief and temporary debt removals still serve to subordinate Caribbean states to the Western capitalist system and the US security apparatus. Those areas hardest hit by storms and less likely to receive aid, continue to be occupied by the poor populations that are largely non-white/Euro peoples. Settlements on islands continue to be concentrated on coasts, where the tourist industry quickly rebuilds its infrastructure post-hurricane and are the first to receive aid. This at once dispels the myths that recovery is impossible, as it happens in the large coastal areas owned and controlled by foreign hotel chains and entities which quickly beckon tourists back to their “lovely beaches” less than a day after a hurricane. Preparedness for hurricanes in the Caribbean islands are “subordinated to political, military, or what today would be called ‘security’ concerns” (Schwartz, 2015, p. 276). I would include economic and ideological concerns as well. These latter concerns are maintained by the wealthiest states in the hemisphere – the United States and Canada.

Hurricane Flora in the 1960s claimed the lives of over 5,000 Haitians under the Duvalier dictatorship – which failed to even warn Haitians about the arrival of the hurricane so that disorder against Duvalier would not take over the country. The lack of preparedness was accepted by both the United States and Canadian governments given their fear of communism in the Caribbean region. Thus “unlike Haiti’s U.S.-backed right-wing president, François Duvalier, Castro’s Communist government ordered residents living in the hurricane’s projected path to evacuate their homes, and if they were unable, to stay and prepare appropriately for the storm.” This preparation and the establishment of Cuba’s defense system in 1966 accounted for significantly less deaths (1,157) in Cuba (Wolfe, 2021). Today, unpreparedness remains a feature in most Caribbean countries that put corporate interests and the interests of the US (and its allies) security objectives above the prioritization of human life and livelihoods in the Caribbean.

As further illustration of this point, even though the 2004 Hurricane Jeanne hit Cuba a lot harder than Haiti – killing 3,000 Haitians – no Cuban lives were lost due to the hurricane (Wolfe, 2021). The historical and present-day case of Haiti is both informative and a cause for worry as we expect future hurricane seasons to be quite bad. Not only is Haiti a fully privatized economy (Wilentz, 2008); but it is also one that has been under the tutelage of the CORE group – a group composed primarily of foreign ambassadors from the US, France, Canada, Spain, Brazil, Germany, and a few representatives from the European Union (EU), the United Nations (UN), and the Organization of American States (OAS) – for over two decades. The CORE group’s tutelage of Haiti has been exceptionally negative, as these states and their ambassadors secure their own corporate and labor interests in the country at the expense of that state’s democracy and national sovereignty (Edmonds, 2024). Thus, disaster preparedness in Haiti has never been an agenda item – and has only gotten worse as those governing the country continue to benefit from political, economic, and environmental disasters there. Present day armed intervention and occupation in Haiti, further makes it unlikely that Haiti will be able to weather the next hurricane season.

Hurricane Unpreparedness, A Note on Canada

It is important to remind here that although much is said about US imperialism and security concerns trumping human rights and pro-people development in the region – Canada is not exempt from this critique. For instance, although Canada touts that its military base (OSH-LAC) in the Caribbean is a “support hub” – that also seeks to assist states experiencing disasters, of which hurricanes are included – in 2017 when Category 5 Hurricane’s Irma and Maria wreaked havoc on Dominica, OSH-LAC warships monitored the situation but provided no on the ground help to Caribbean peoples there (John, 2024, p. 12-3). The Canadian government also enacted restrictive migration policies towards those fleeing from the hurricane and its damages. This practice would be repeated by Canada again in 2019 during the aftermath of Hurricane Dorian in The Bahamas (John, 2024, p. 12-3). Given that I am currently living in Canada, it is important to point out that Canada is a state that frequently touts progressive rhetoric on climate change, resiliency, and disaster preparedness in the Caribbean region. However, Canada’s actions continue to render the Caribbean region unprepared alongside the actions of the US.

In the 2023 Canada-CARICOM summit hosted by Canada, Caribbean prime ministers sought to place climate issues and climate infrastructure at the top of the agenda – however, Canada was mainly concerned with getting support for an armed intervention in Haiti (Thurton, 2023). Haiti remains the most unprepared country in the Caribbean when disasters hit, which made Canada’s insistence on armed intervention and occupation even more tone deaf. Haiti’s unpreparedness is directly tied to US, Canada, France, and CORE group members tutelage and rejection of Haitian democracy ever since that country’s integration into the Western capitalist system via US occupation. These examples illuminate the fact that the wealthier states in the Western Hemisphere, namely the US and Canada, actively disregard the lives of those impacted by hurricanes and other natural disasters to their south – while first and foremost safeguarding their own economic, ideological, and security priorities. In my analysis of ‘south,’ the Caribbean, the Yucatán Peninsula, the Gulf of Mexico, and the South-Eastern United States are included.

Conclusion

Ideologically, the promotion of capitalism, colonialism, and imperialism in the Caribbean (of which the South-Eastern United States, the Gulf of Mexico and Yucatán Peninsula is included) continues to pose an obstacle to disaster preparedness in a region prone to hurricanes. More importantly, the promotion of these harmful ideologies often comes at the expense of human life. Nothing makes this clearer than the fact that it is the revolutionary state – which is also the most heavily economically sanctioned state in the region – Cuba, that continues to be the most prepared state in times of disaster. This stands in stark contrast to other Caribbean states and to wealthier states, like the US, which mandate regional unpreparedness. Today, while we await (but hope that it is not so) a bad hurricane season, the Caribbean region is more militarized than it has been since the end of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st century. Militarization is directly due to US security objectives that aim to keep China’s investments (thus competition) out of the region. This policy is backed by Canada, which seeks to advance its own corporate interests in the region.

The US and Canada continue to militarize the Caribbean region, exacerbating climate change and neglecting the urgency of developing resiliency infrastructure. In fact, militarization in the Caribbean region today (and in Africa and Asia) occurs alongside the tightening of both the US and Canadian borders given hostile narratives towards immigrants and immigration within them. This even with the region’s long history (as has been pointed out) of people fleeing the region both during and after a hurricane. All of which indicates that while these states are undoubtedly deepening the climate crisis with their global “security” endeavors, they view the people harmed and negatively impacted by their actions as disposable.

Postscript

Three months after the writing of this document, 5 hurricanes – Debby, Ernesto, Francine, Helene, and Milton – have impacted peoples and infrastructure in the south. The 2024 Atlantic Hurricane season thus far (October 11th, 2024) has taken almost 400 lives – with the actual figure being uncertain, given that the damage from Milton is still being assessed. Each storm is estimated to have cost between $80 – $250 billion (USD) in damages across the region. While governments talk about costs and recovery efforts to get economies “back on track” and provide people with temporary and conditional aid – which is the post disaster norm – we are presented with an uncomfortable, yet undeniable fact: states in the region, whether by colonial inheritance or commitment to capitalism, are banking on unpreparedness continuing well into the future. We must be proactive in defeating this dangerous ideology that places people’s lives, livelihoods and the physical environment at stake; while perpetuating, in its aftermath, conditions that make it so.

References

Clark, John I, and Léon Tabah, eds. 1995. Population and Environment Population – Environment – Development Interactions. Paris, France: Comité International de Coopération dans les Recherches Nationales en Démographie (CICRED). http://www.cicred.org/Eng/Publications/pdf/c-a1.pdf.

Direct Relief. 2024. “Direct Relief Responds as Hurricane Beryl Impacts the Caribbean. The Region, Watchful and Ready, Will Weather the Storm Today.” Direct Relief. https://www.directrelief.org/2024/07/direct-relief-responds-as-hurricane-beryl-impacts-the-caribbean-the-region-watchful-and-ready-will-weather-the-storm-today/.

Edmonds, Kevin. 2024. “CARICOM, Regional Arm of the Core Group, Sells Out Haiti Again.” Black Agenda Report. https://www.blackagendareport.com/caricom-regional-arm-core-group-sells-out-haiti-again.

Forecast Centre. 2024. “Atlantic Canada Next in Line for a Soaking, Flood Risk from Beryl Remnants.” The Weather Network.https://www.theweathernetwork.com/en/news/weather/forecasts/atlantic-canada-next-in-line-for-a-soaking-flood-risk-from-beryl-remnants.

IFRC. 2024. “Humanitarian Needs Ramp up in the Aftermath of ‘unprecedented’ Hurricane Beryl, Signaling New Reality for Caribbean.” The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). https://www.ifrc.org/press-release/humanitarian-needs-ramp-aftermath-unprecedented-hurricane-beryl-signaling-new-reality.

Jobson, Ryan C. 2024. “Hurricane Beryl at the Gates: The Grenadines and Caribbean Autonomy.” Medium. https://medium.com/clash-voices-for-a-caribbean-federation-from-below/hurricane-beryl-at-the-gates-the-grenadines-and-caribbean-autonomy-86834fb43bcd.

John, Tamanisha J. 2023. “Canadian Imperialism in Caribbean Structural Adjustment, 1980-2000.” In Class Power and Capitalism, Brill Publishers, 136–79.

John, Tamanisha J. 2024. “Capitalism, Global Militarism, and Canada’s Investment in the Caribbean.” Class, Race and Corporate Power 12(1): 25.

Loop News. 2024. “Caribbean 2024 Heat Season Could Climb to Near-Record Heat.” Caribbean Loop News. https://caribbean.loopnews.com/content/caribbean-2024-heat-season-could-climb-near-record-heat.

McGrath, Gareth. 2024. “Hurricane Beryl Was the Earliest Category 5 Storm. What Could That Mean for NC?” Star News Online. https://www.starnewsonline.com/story/news/local/2024/07/11/what-hurricane-beryl-the-earliest-category-5-storm-could-mean-for-nc/74288495007/.

Mulcahy, Matthew. 2006. Hurricanes and Society in the British Greater Caribbean, 1624 – 1783. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

NACLA. 2024. “This Week: Hurricane Beryl Slams the Caribbean, a Victory for Midwives in Mexico, Venezuelan Elections, and More.” https://nacla.salsalabs.org/july_12_24?wvpId=37c1b636-52b7-44b5-af75-9a38617519d5.

NASA. 2024. “Carriacou After Beryl.” NASA Earth Observatory. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/153039/carriacou-after-beryl.

Pérez Jr., Louis A. 2001. Winds of Change: Hurricanes & The Transformation of Nineteenth-Century Cuba. Chapel Hill & London: The University of North Carolina Press.

Rodney, Walter. 2018. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Verso Books.

Schwartz, Stuart B. 2015. Sea of Storms: A History of Hurricanes in the Greater Caribbean from Columbus to Katrina. Princeton University Press.

Thomas, Clive Y. 1984. Plantations, Peasants and State: A Study of the Mode of Sugar Production in Guyana. Los Angeles: UCLA Center for Afro-American Studies.

Thurton, David. 2023. “Caribbean Looks to Trudeau to Put Quest for Climate Change Funding on the World’s Agenda.” CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/caricom-trudeau-caribbean-1.6999106.

TT Weather Center. 2024. “Hurricane Beryl Death Toll Now At 33.” Trinidad and Tobago Weather Center. https://ttweathercenter.com/2024/07/11/hurricane-beryl-death-toll-now-at-33/.

VOA News. 2024. “Remnants of Beryl Flood Northeast US.” VOA News. https://www.voanews.com/a/remnants-of-beryl-flood-northeast-us/7694063.html#.

Wagner, Bryce, and Cristiana Mesquita. 2024. “In St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Beryl Nearly Erased the Smallest Inhabited Island from the Map.” AP News. https://apnews.com/article/hurricane-beryl-mayreau-island-caribbean-bb64fc9b61da76685704b8f42f97736c?eType=EmailBlastContent&eId=fffcba4b-3154-47e9-b4ce-e0349f4225db.

Wilentz, Amy. 2008. “Hurricanes and Haiti.” Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/la-oe-wilentz13-2008sep13-story.html.

Wolfe, Mikael. 2021. “When It Comes to Hurricanes, the U.S. Can Learn a Lot from Cuba: Cuba Devised a System That Minimizes Death and Destruction from Hurricanes.” The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/09/01/when-it-comes-hurricanes-us-can-learn-lot-cuba/.

Zodgekar, Ketaki, Avery Raines, Fayola Jacobs, and Patrick Bigger. 2023. A Dangerous Debt-Climate Nexus. NACLA Report on the Americas. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714839.2023.2247773.

Photo Credit: InOldNews, by Delia Louis

Description: Depicts St. Lucia during and post Hurricane Beryl

License info: Creative Commons taken from Flickr.

About the author: Tamanisha J. John is an Assistant Professor at York University in the Department of Politics