Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Himanshu Gupta, Senior Research Fellow (Lived Experience), Rural and Remote Health, Flinders University

Australians lose around A$25 billion on legal forms of gambling each year, representing the largest per person losses in the world.

Gambling harms – including financial, emotional, social and psychological costs – extend to loved ones, peers and co-workers and the community. And some communities are impacted differently to others.

The Northern Territory has a growing multicultural population, with 22% of residents born overseas and 33% speaking a language other than English at home.

About 37% of multicultural Territorians are considered at-risk gamblers, compared to 14% in English speaking households.

Many migrants, including those in the NT, experience financial, social, and emotional pressures, which sometimes lead them to gambling as a means of socialisation or stress relief. Our research explores why and what might limit the risks and harms.

Read more:

Pokies? Lotto? Sports betting? Which forms of problem gambling affect Australians the most?

‘There’s not much to do’

Published earlier this year, our lived experience study explored the pressures that make gambling appealing to migrant communities.

For example, scarce recreational options in Darwin mean gambling fills a social gap. As one person we spoke to said,

It’s kind of the entertainment for us in Darwin […] there’s not much to do, so we go to the casino for fun with friends.

Gambling can become a way to socialise in the absence of other affordable, culturally relevant options.

But what begins as a casual activity can quickly lead to personal strain. Some participants in our study described family tensions.

My sister and brother-in-law got into fighting […] she said, ‘Why do you have to spend a lot of money on gambling?’ but he said, ‘That’s my hobby.’

Another person revealed how gambling impacts family dynamics:

My husband not being present most of the time because he is out gambling has really impacted me […] the kids are missing their dad. I’m missing my husband.

‘Sometimes you can win some money’

Financial stress is a significant factor increasing gambling risks, especially among migrants on temporary visas who face job and visa uncertainties.

Some migrants view gambling as a potential escape from financial pressures, as an international student explained to us,

It is common for international students to stake their tuition fees at the casino […] sometimes you can win some money.

However, gambling losses often exacerbated financial hardship, trapping individuals in cycles of debt and loss.

‘I never gambled until I came to Australia’

The NT’s legal and accessible gambling environment also plays a role, especially for migrants from countries where gambling is restricted.

A participant from Bangladesh shared,

In my country, gambling is not a good thing […] I never gambled until I came to Australia.

Another believed that

Betting on soccer is an easy way to make money […] but in Africa, I didn’t have access to as much funds as I have here [in Australia].

The perceived ease of earning money through gambling adds to the temptation, particularly in times of financial uncertainty.

PhotopankPL/Shutterstock

‘I feel shameful talking about it’

Another critical factor is the reluctance to seek help, often due to cultural stigma or language barriers. Many migrants prefer to manage gambling issues privately. One participant stated,

In my culture, gambling is seen as a bad behaviour […] I just feel shameful talking about it.

Others expressed scepticism toward counselling, viewing it as ineffective. This reluctance can lead to isolation, with individuals and families managing gambling harms in private, often unaware of local support options.

The impacts of gambling extend to mental health, with participants describing cycles of guilt, shame and financial stress. A participant explained how online gambling worsened their addiction

My gambling problem grew worse […] I started spending more money than I had any right to be spending […] we always ended up going back to the casino or poker site until our bank account was empty.

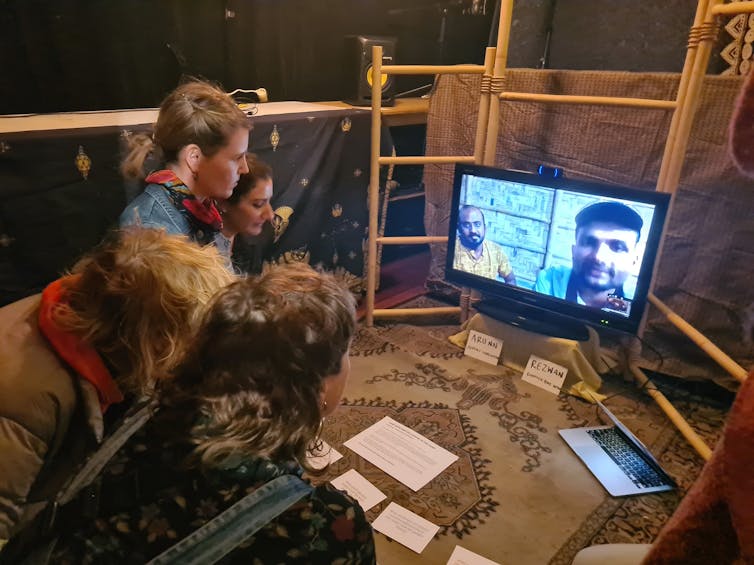

Culturally sensitive approaches are needed

Our research shows culturally sensitive approaches are essential to address gambling harms effectively. This is includes raising awareness about gambling risks in a way that resonates with diverse communities.

Further, our research participants reported higher rates of gambling among Filipino, East Asian and African communities, with the issue anecdotally more common among women in certain Asian groups.

Expanding culturally relevant recreational opportunities could help provide a healthier alternative to gambling.

Support services should also be tailored to migrant need.

Language-specific counselling and culturally competent resources could encourage migrants to seek help. Policymakers could consider revising gambling advertising and venue availability to reduce exposure, especially in vulnerable communities.

Addressing gambling harms among migrants, including those in NT, requires collective efforts from policymakers, community leaders and local organisations.

![]()

Himanshu Gupta receives funding from Attorney General and Justice Department, Northern Territory government.

Devaki Monani is the current Chair of the Minister’s Advisory Council for Multicultural Affairs (MACMA), Northern Territory

James Smith is a member of the Strategic Advisory Group for the National Centre for Education and Training in Addiction, deputy chair of the Association for Alcohol and Other Drugs Agencies NT and a fellow and life member of the Australian Health Promotion Association.

Noemi Tari-Keresztes receives funding from NT government community benefit funding. She is an Honorary Member of the NT Lived Experience Network.

– ref. Financial stress and cultural differences make migrants particularly vulnerable to gambling harms. Here’s why – https://theconversation.com/financial-stress-and-cultural-differences-make-migrants-particularly-vulnerable-to-gambling-harms-heres-why-243042