An exiled West Papuan leader has called for unity among his people in the face of a renewed “colonial grip” of Indonesia’s new president.

President Prabowo Subianto, who took office last month, “is a deep concern for all West Papuans”, said Benny Wenda of the United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP).

Speaking at the Oxford Green Fair yesterday — Morning Star flag-raising day — ULMWP’s interim president said Prabowo had already “sent thousands of additional troops to West Papua” and restarted the illegal settlement programme that had marginalised Papuans and made them a minority in their own land.

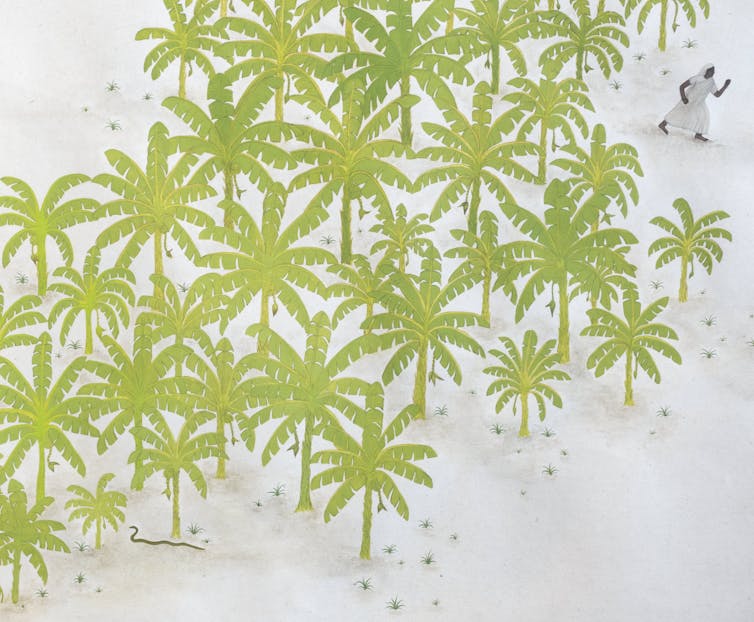

“He is continuing to destroy our land to create the biggest deforestation project in the history of the world. This network of sugarcane and rice plantations is as big as Wales.

“But we cannot panic. The threat from [President] Prabowo shows that unity and direction is more important than ever.

Indonesia doesn’t fear a divided movement. They do fear the ULMWP, because they know we are the most serious and direct challenge to their colonial grip.”

Here is the text of the speech that Wenda gave while opening the Oxford Green Fair at Oxford Town Hall:

Wenda’s speech

December 1st is the day the West Papuan nation was born.

On this day 63 years ago, the New Guinea Council raised the Morning Star across West Papua for the first time.

We sang our national anthem and announced our Parliament, in a ceremony recognised by Australia, the UK, France, and the Netherlands, our former coloniser. But our new state was quickly stolen from us by Indonesian colonialism.

This day is important to all West Papuans. While we remember all those we have lost in the struggle, we also celebrate our continued resistance to Indonesian colonialism.

On this day in 2020, we announced the formation of the Provisional Government of West Papua. Since then, we have built up our strength on the ground. We now have a constitution, a cabinet, a Green State Vision, and seven executives representing the seven customary regions of West Papua.

Most importantly, we have a people’s mandate. The 2023 ULMWP Congress was first ever democratic election in the history. Over 5000 West Papuans gathered in Jayapura to choose their leaders and take ownership of their movement. This was a huge sacrifice for those on the ground. But it was necessary to show that we are implementing democracy before we have achieved independence.

The outcome of this historic event was the clarification and confirmation of our roadmap by the people. Our three agendas have been endorsed by Congress: full membership of the MSG [Melanesian Spearhead Group], a UN High Commissioner for Human Rights visit to West Papua, and a resolution at the UN General Assembly. Through our Congress, we place the West Papuan struggle directly in the hands of the people. Whenever our moment comes, the ULMWP will be ready to seize it.

Differing views

I want to remind the world that internal division is an inevitable part of any revolution. No national struggle has avoided it. In any democratic country or movement, there will be differing views and approaches.

But the ULMWP and our constitution is the only way to achieve our goal of liberation. We are demonstrating to Indonesia that we are not separatists, bending this way and that way: we are a government-in-waiting representing the unified will of our people. Through the provisional government we are reclaiming our sovereignty. And as a government, we are ready to engage with the world. We are ready to engage with Indonesia as full members of the Melanesian Spearhead Group, and we believe we will achieve this crucial goal in 2024.

The importance of unity is also reflected in the ULMWP’s approach to West Papuan history. As enshrined in our constitution, the ULMWP recognises all previous declarations as legitimate and historic moments in our struggle. This does not just include 1961, but also the OPM Independence Declaration 1971, the 14-star declaration of West Melanesia in 1988, the Papuan People’s Congress in 2000, and the Third West Papuan Congress in 2011.

All these announcements represent an absolute rejection of Indonesian colonialism. The spirit of Merdeka is in all of them.

The new Indonesian President, Prabowo Subianto, is a deep concern for all West Papuans. He has already sent thousands of additional troops to West Papua and restarted the illegal settlement programme that has marginalised us and made us a minority in our own land. He is continuing to destroy our land to create the biggest deforestation project in the history of the world. This network of sugarcane and rice plantations is as big as Wales.

But we cannot panic. The threat from Prabowo shows that unity and direction is more important than ever. Indonesia doesn’t fear a divided movement. They do fear the ULMWP, because they know we are the most serious and direct challenge to their colonial grip.

I therefore call on all West Papuans, whether in the cities, the bush, the refugee camps or in exile, to unite behind the ULMWP Provisional Government. We work towards this agenda at every opportunity. We continue to pressure on United Nations and the international community to review the fraudulent ‘Act of No Choice’, and to uphold my people’s legal and moral right to choose our own destiny.

I also call on all our solidarity groups to respect our Congress and our people’s mandate. The democratic right of the people of West Papua needs to be acknowledged.

What does amnesty mean?

Prabowo has also mentioned an amnesty for West Papuan political prisoners. What does this amnesty mean? Does amnesty mean I can return to West Papua and lead the struggle from inside? All West Papuans support independence; all West Papuans want to raise the Morning Star; all West Papuans want to be free from colonial rule.

But pro-independence actions of any kind are illegal in West Papua. If we raise our flag or talk about self-determination, we are beaten, arrested or jailed. The whole world saw what happened to Defianus Kogoya in April. He was tortured, stabbed, and kicked in a barrel full of bloody water. If the offer of amnesty is real, it must involve releasing all West Papuan political prisoners. It must involve allowing us to peacefully struggle for our freedom without the threat of imprisonment.

Despite Prabowo’s election, this has been a year of progress for our struggle. The Pacific Islands Forum reaffirmed their call for a UN Human Rights Visit to West Papua. This is not just our demand – more than 100 nations have now insisted on this important visit. We have built vital new links across the world, including through our ULMWP delegation at the UN General Assembly.

Through the creation of the West Papua People’s Liberation Front (GR-PWP), our struggle on the ground has reached new heights. Thank you and congratulations to the GR-PWP Administration for your work.

Thank you also to the KNPB and the Alliance of Papuan Students, you are vital elements in our fight for self-determination and are acknowledged in our Congress resolutions. You carry the spirit of Merdeka with you.

I invite all solidarity organisations, including Indonesian solidarity, around the world to preserve our unity by respecting our constitution and Congress. To Indonesian settlers living in our ancestral land, please respect our struggle for self-determination. I also ask that all our military wings unite under the constitution and respect the democratic Congress resolutions.

I invite all West Papuans – living in the bush, in exile, in refugee camps, in the cities or villages – to unite behind your constitution. We are stronger together.

Thank you to Vanuatu

A special thank you to Vanuatu government and people, who are our most consistent and strongest supporters. Thank you to Fiji, Kanaky, PNG, Solomon Islands, and to Pacific Islands Forum and MSG for reaffirming your support for a UN visit. Thank you to the International Lawyers for West Papua and the International Parliamentarians for West Papua.

I hope you will continue to support the West Papuan struggle for self-determination. This is a moral obligation for all Pacific people. Thank you to all religious leaders, and particularly the Pacific Council of Churches and the West Papua Council of Churches, for your consistent support and prayers.

Thank you to all the solidarity groups in the Pacific who are tirelessly supporting the campaign, and in Europe, Australia, Africa, and the Caribbean.

I also give thanks to the West Papua Legislative Council, Buchtar Tabuni and Bazoka Logo, to the Judicative Council and to Prime Minister Edison Waromi. Your work to build our capacity on the ground is incredible and essential to all our achievements. You have pushed forwards all our recent milestones, our Congress, our constitution, government, cabinet, and vision.

Together, we are proving to the world and to Indonesia that we are ready to govern our own affairs.

To the people of West Papua, stay strong and determined. Independence is coming. One day soon we will walk our mountains and rivers without fear of Indonesian soldiers. The Morning Star will fly freely alongside other independent countries of the Pacific.

Until then, stay focused and have courage. The struggle is long but we will win. Your ancestors are with you.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz