Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Adrian Beaumont, Election Analyst (Psephologist) at The Conversation; and Honorary Associate, School of Mathematics and Statistics, The University of Melbourne

A national Freshwater poll for The Financial Review, conducted January 17–19 from a sample of 1,063, gave the Coalition a 51–49 lead, unchanged since December. Primary votes were 40% Coalition (steady), 32% Labor (up two), 13% Greens (down one) and 15% for all Others (down one).

As is the case with YouGov below, Freshwater uses 2022 preference flows for its two-party estimates, and applying 2022 preference flows to the primary votes would give about a 50–50 tie, so rounding probably contributed to the Coalition’s lead in both Freshwater and YouGov polls.

Anthony Albanese’s net approval was down one point to -18, with 50% unfavourable and 32% favourable. Peter Dutton’s net approval was also down one to -4. Albanese and Dutton were tied 43–43 as preferred PM after Albanese led by 46–43 in December, the first time Albanese has not led in this poll.

When voters were asked to rate their top three issues, the cost of living was easily highest with 73% rating it a top three issue, followed by housing at 42%, health at 28%, economic management at 27% and crime at 26%. Crime was up three since December, while the environment was down six to 18%.

YouGov poll and economic data

A YouGov national poll, conducted January 9–15 from a sample of 1,504, gave the Coalition a 51–49 lead, a one-point gain for the Coalition since the November YouGov poll. Primary votes were 39% Coalition (up one), 32% Labor (up two), 12% Greens (down one), 7% One Nation (down two) and 10% for all Others (steady).

Albanese’s net approval was up five points to -15, with 55% dissatisfied and 40% satisfied. Dutton’s net approval was up two to -6. Albanese led Dutton as better PM by 44–40 (42–39 in November).

The Australian Bureau of Statistics released December jobs data last Thursday. The unemployment rate rose 0.1% from November to 4.0%, but this was due to a higher participation rate. The employment population ratio (the percentage of eligible Australians employed) rose 0.2% to 64.5%, a record high.

The ABC’s report said economists thought a February rate cut was less likely as a result of the jobs data, but market traders disagreed with this assessment.

Morgan poll: Coalition ahead

A national Morgan poll, conducted January 6–12 from a sample of 1,721, gave the Coalition a 51.5–48.5 lead using respondent preferences, a 1.5-point gain for Labor since the previous poll.

Primary votes were 40.5% Coalition (steady), 30% Labor (down one), 12.5% Greens (up 0.5), 4.5% One Nation (up one), 9% independents (down 0.5) and 3.5% others (steady). By 2022 election preferences, this poll gave the Coalition a 50.5–49.5 lead, a 0.5-point gain for the Coalition.

The previous Morgan poll, conducted December 30 to January 5 from a sample of 1,446, gave the Coalition a 53–47 lead using respondent preferences, a one-point gain for the Coalition since mid-December.

Primary votes were 40.5% Coalition (down 0.5), 31% Labor (up 3.5), 12% Greens (down 0.5), 3.5% One Nation (down 1.5), 9.5% independents (down one) and 3.5% others (steady).

Despite Labor’s improved primary vote, its two-party share slid owing to a highly unlikely shift with Greens preferences (from 85% to Labor in mid-December to 55% in this poll). An estimate based on the primary votes would have a 50–50 tie by 2022 election preference flows, a 1.5-point gain for Labor.

A new graph to follow the polls ahead of the 2025 election

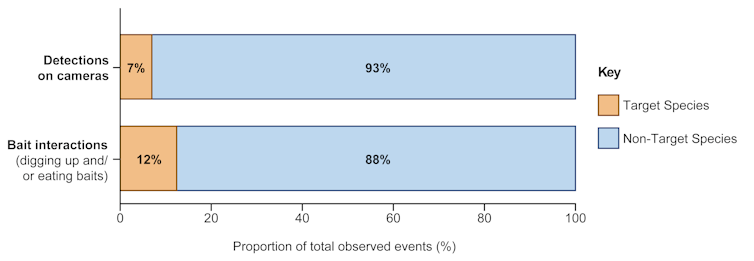

I will be using the graph below to follow the polls in the lead-up to the federal election that will be held by May. The graph will chart polls from seven pollsters: Newspoll, Resolve, Freshwater, YouGov, Redbridge, Morgan and Essential. The graph starts with the last 2024 poll from each pollster.

This graph uses the 2022 election preference flows from each pollster to obtain its two-party estimates. If this was not given by the pollster, it was estimated from the primary votes.

So far this year, Morgan, YouGov and Freshwater have released new polls. These are marked by a line connecting the new polls with the previous ones. Overall, the Coalition still holds a narrow lead, with the picture unchanged from December. However, Labor was probably unlucky not to get a 50–50 tie from either YouGov or Freshwater.

Respondent preference flows from Morgan and Essential have usually been worse for Labor than the last election method, and One Nation preferences were stronger for the Liberal National Party at the October Queensland election than in 2020, so it’s reasonable to expect Labor to under-perform the 2022 election flows.

Most pollsters don’t give a respondent preference figure, and these figures are more volatile from poll to poll, and do not necessarily reflect changes in primary votes. Therefore, I will use the 2022 preference method in the graph.

The fieldwork midpoint date gives a better indication of how recent a poll is than the final fieldwork date. A poll that was conducted over a long period may have a more recent final date than a poll with shorter fieldwork, but the majority of the poll with shorter fieldwork may have been conducted before the poll with longer fieldwork.

Newspoll aggregate data for October to December

On December 26, The Australian released aggregate data for the three national Newspolls taken between October 7 and December 6, which had a total sample of 3,775. Comparisons are with the July to September Newspoll aggregate.

The Poll Bludger said that in New South Wales, there was a 50–50 tie, a one-point gain for Labor. In Victoria, there was a 50–50 tie, a two-point gain for the Coalition. In Queensland, the Coalition had a 53–47 lead, a one-point gain for Labor. In Western Australia, Labor led by 54–46, a two-point gain for Labor. In South Australia, Labor led by 53–47, a one-point gain for the Coalition.

The Poll Bludger’s BludgerTrack data says that among university-educated people, Labor led by 51–49, a two-point gain for the Coalition. Labor led by 51–49 with those with a TAFE or technical education, a one-point gain for Labor. The Coalition led by 53–47 with those without any tertiary education, a two-point gain for the Coalition.

Resolve likeability ratings

Nine newspapers on December 29 released likeability ratings from Resolve’s early December national poll that had the worst position for Labor this term. Jacqui Lambie was the most liked federal politician at +14 net likeability, with Jacinta Price second at +8. Penny Wong was the only Labor politician at net positive, scoring +2.

Other prominent Labor ministers were negative, with Tanya Plibersek at -5, Jim Chalmers at -7 and Chris Bowen at -11. Pauline Hanson and Greens leader Adam Bandt were both at -13, Barnaby Joyce at -22 and Lidia Thorpe at -41.

Albanese’s net likeability of =17 is better than his -26 net approval from this poll, while Dutton’s net zero likeability is also marginally higher than his -2 net approval.

Left-wing parties face dismal result at German election

In early November the German federal coalition of centre-left SPD, Greens and pro-business FDP collapsed, and an election will be held on February 23, seven months early. Polls suggest a dismal result for the coalition parties. I covered this election for The Poll Bludger on December 28.

The impeachment of South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol, the new French PM and a wrap of recent international elections were also included.

Adrian Beaumont does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Coalition still ahead in latest polls, but some promising news for Labor – https://theconversation.com/coalition-still-ahead-in-latest-polls-but-some-promising-news-for-labor-246544