Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Albert Van Dijk, Professor, Water and Landscape Dynamics, Fenner School of Environment & Society, Australian National University

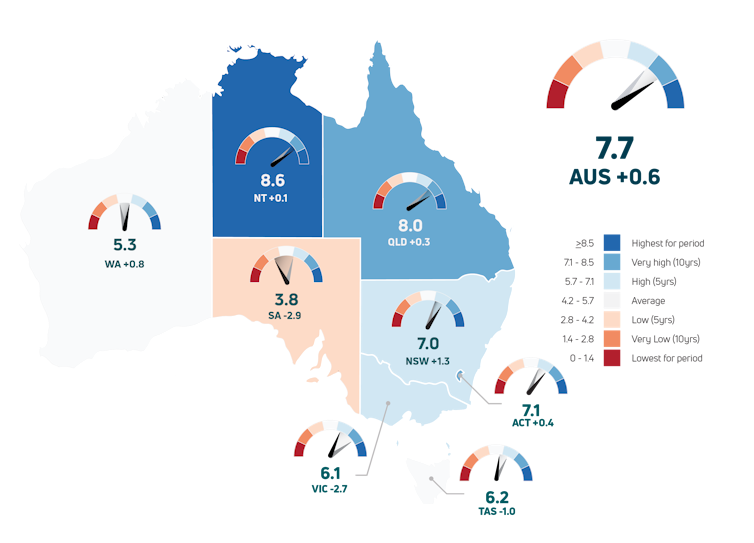

For the fourth year running, the condition of Australia’s environment has been relatively good overall. Our national environment scorecard released today gives 2024 a mark of 7.7 out of 10.

You might wonder how this can be. After all, climate change is intensifying and threatened species are still in decline.

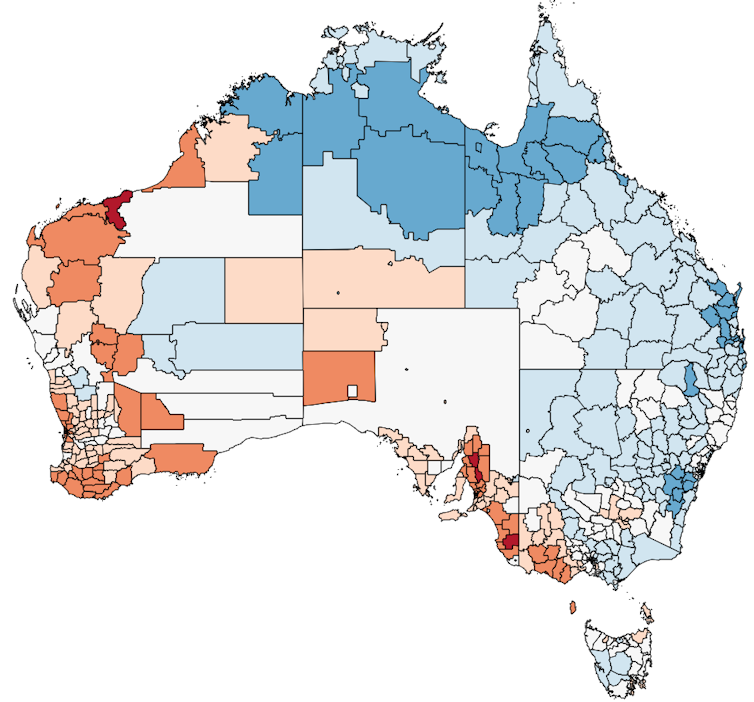

The main reason: good rainfall partly offset the impact of global warming. In many parts of Australia, rainfall, soil water and river flows were well above average, there were fewer large bushfires, and vegetation continued to grow. Overall, conditions were above average in the wetter north and east of Australia, although parts of the south and west were very dry.

But this is no cause for complacency. Australia’s environment remains under intense pressure. Favourable conditions have simply offered a welcome but temporary reprieve. As a nation we must grasp the opportunity now to implement lasting solutions before the next cycle of drought and fire comes around.

Australia’s Environment Report 2024, CC BY-NC-ND

Preparing the national scorecard

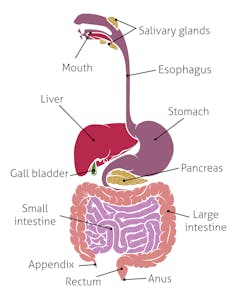

For the tenth year running, we have trawled through a huge amount of data from satellites, weather and water measuring stations, and ecological surveys.

We gathered information about climate change, oceans, people, weather, water, soils, plants, fire and biodiversity.

Then we analysed the data and summarised it all in a report that includes an overall score for the environment. This score (between zero and ten) gives a relative measure of how favourable conditions were for nature, agriculture and our way of life over the past year in comparison to all years since 2000. This is the period we have reliable records for.

While it is a national report, conditions vary enormously between regions and so we also prepare regional scorecards. You can download the scorecard for your region at our website.

Australia’s Environment Report 2024, CC BY-NC-ND

Welcome news, but alarming trends continue

Globally, 2024 was the world’s hottest year on record. It was Australia’s second hottest year, with the record warmest sea surface temperatures. As a result, the Great Barrier Reef experienced its fifth mass bleaching event since 2016, while Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia also experienced bleaching.

Yet bushfire activity was low despite high temperatures, thanks to regular rainfall.

National rainfall was 18% above average, improving soil condition and increasing tree canopy cover.

States such as New South Wales saw notable improvements in environmental conditions, while conditions also improved somewhat in Western Australia. Others experienced declines, particularly South Australia, Victoria, and Tasmania. These regional contrasts were largely driven by rainfall – good rains can hide some underlying environmental degradation trends.

Favourable weather conditions bumped up the nation’s score this year, rather than sustained environmental improvements.

Australia’s Environment Explorer, CC BY-NC-ND

A temporary respite?

The past four years show Australia’s environment is capable of bouncing back from drought and fire when conditions are right.

But the global climate crisis continues to escalate, and Australia remains highly vulnerable. Rising sea levels, more extreme weather and fire events continue to threaten our environment and livelihoods. The consequences of extreme events can persist for many years, like we have seen for the Black Summer of 2019–20.

To play our part in limiting global warming, Australia needs to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. Progress is stalling: last year, national emissions fell slightly (0.6%) below 2023 levels but were still higher than in 2022. Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions per person remain among the highest in the world.

Biodiversity loss remains an urgent issue. The national threatened species list grew by 41 species in 2024. While this figure is much lower than the record of 130 species added in 2023, it remains well above the long-term average of 25 species added per year.

More than half of the newly listed or uplisted species were directly affected by the Black Summer fires. Meanwhile, habitat destruction and invasive species continue to put pressure on native ecosystems and species.

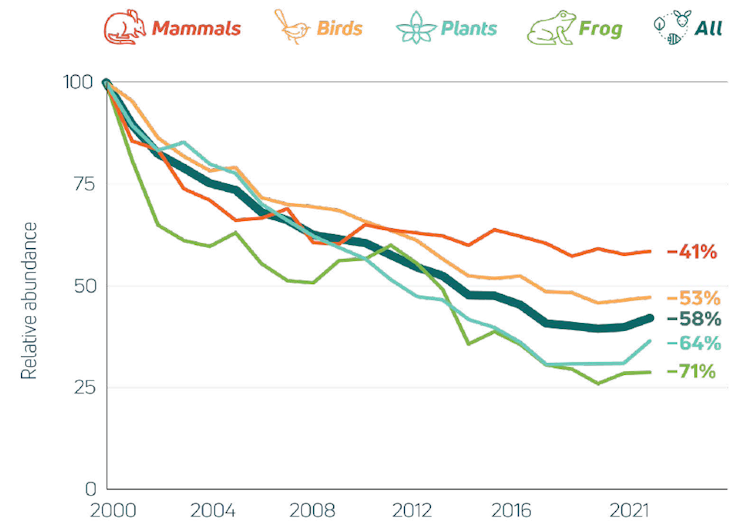

The Threatened Species Index captures data from long-term threatened species monitoring. The index is updated annually but with a three-year lag due largely to delays in data processing and sharing. This means the 2024 index includes data up to 2021.

The index revealed the abundance of threatened birds, mammals, plants, and frogs has fallen an average of 58% since 2000.

But there may be some good news. Between 2020 and 2021, the overall index increased slightly (2%) suggesting the decline has stabilised and some recovery is evident across species groups. We’ll need further monitoring to confirm whether this represents a lasting turnaround or a temporary pause in declines.

Australia’s Environment Report 2024, CC BY-NC-ND

What needs to happen?

The 2024 Australia’s Environment Report offers a cautiously optimistic picture of the present. Without intervention, the future will look a lot worse.

Australia must act decisively to secure our nation’s environmental future. This includes reducing greenhouse gas emissions, introducing stronger land management policies and increasing conservation efforts to maintain and restore our ecosystems.

Without redoubling our efforts, the apparent environmental improvements will not be more than a temporary pause in a long-term downward trend.

![]()

Australia’s Environment Report is produced by the ANU Fenner School for Environment & Society and the Terrestrial Ecosystem Research Network (TERN), which is enabled by the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy.

Albert Van Dijk receives or has previously received funding from several government-funded agencies, grant schemes and programs.

Shoshana Rapley is a Research Assistant and PhD candidate at the Australian National University and has received funding from the Ecological Society of Australia and BirdLife Australia.

Tayla Lawrie is a current employee of the Terrestrial Ecosystem Research Network (TERN), funded by the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy.

– ref. Rain gave Australia’s environment a fourth year of reprieve in 2024 – but this masks deepening problems: report – https://theconversation.com/rain-gave-australias-environment-a-fourth-year-of-reprieve-in-2024-but-this-masks-deepening-problems-report-252183