Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Maurizio Valsania, Professor of American History, Università di Torino

The day after conservative activist Charlie Kirk was shot and killed while speaking at Utah Valley University, commentators repeated a familiar refrain: “This isn’t who we are as Americans.”

Others similarly weighed in. Whoopi Goldberg on “The View” declared that Americans solve political disagreements peacefully: “This is not the way we do it.”

Yet other awful episodes come immediately to mind: President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed on Nov. 22, 1963. More recently, on June 14, 2025, Melissa Hortman, speaker emerita of the Minnesota House of Representatives, was shot and killed at her home, along with her husband and their golden retriever.

As a historian of the early republic, I believe that seeing this violence in America as distinct “episodes” is wrong.

Instead, they reflect a recurrent pattern.

American politics has long personalized its violence. Time and again, history’s advance has been imagined to depend on silencing or destroying a single figure – the rival who becomes the ultimate, despicable foe.

Hence, to claim that such shootings betray “who we are” is to forget that the U.S. was founded upon – and has long been sustained by – this very form of political violence.

Bettman/Getty Images

Revolutionary violence as political theater

The years of the American Revolution were incubated in violence. One abominable practice used on political adversaries was tarring and feathering. It was a punishment imported from Europe and popularized by the Sons of Liberty in the late 1760s, Colonial activists who resisted British rule.

In seaport towns such as Boston and New York, mobs stripped political enemies, usually suspected loyalists – supporters of British rule – or officials representing the king, smeared them with hot tar, rolled them in feathers, and paraded them through the streets.

The effects on bodies were devastating. As the tar was peeled away, flesh came off in strips. People would survive the punishment, but they would carry the scars for the rest of their life.

By the late 1770s, the Revolution in what is known as the Middle Colonies had become a brutal civil war. In New York and New Jersey, patriot militias, loyalist partisans and British regulars raided across county lines, targeting farms and neighbors. When patriot forces captured loyalist irregulars – often called “Tories” or “refugees” – they frequently treated them not as prisoners of war but as traitors, executing them swiftly, usually by hanging.

In September 1779, six loyalists were caught near Hackensack, New Jersey. They were hanged without trial by patriot militia. Similarly, in October 1779, two suspected Tory spies captured in the Hudson Highlands were shot on the spot, their execution justified as punishment for treason.

To patriots, these killings were deterrence; to loyalists, they were murder. Either way, they were unmistakably political, eliminating enemies whose “crime” was allegiance to the wrong side.

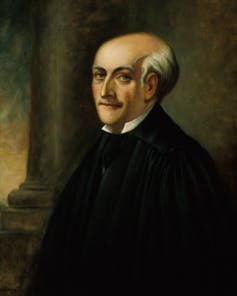

US Supreme Court

Pistols at dawn: Dueling as politics

Even after independence, the workings of American politics remained grounded in a logic of violence toward adversaries.

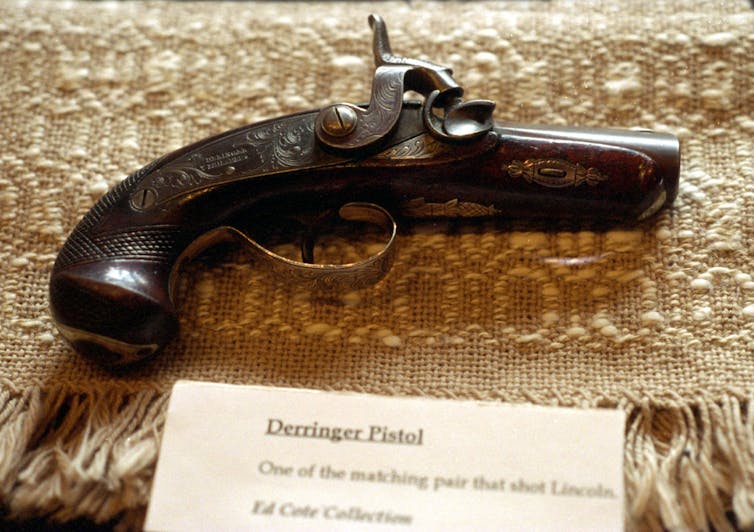

For national leaders, the pistol duel was not just about honor. It normalized a political culture where gunfire itself was treated as part of the debate.

The most famous duel, of course, was Aaron Burr’s killing of Alexander Hamilton in 1804. But scores of lesser-known confrontations dotted the decade before it.

In 1798, Henry Brockholst Livingston – later a U.S. Supreme Court justice – killed James Jones in a duel. Far from discredited, he was deemed to have acted honorably. In the early republic, even homicide could be absorbed into politics when cloaked in ritual. Ironically, Livingston had survived an assassination attempt in 1785.

In 1802, another shameful spectacle unfolded: New York Democratic-Republicans DeWitt Clinton and John Swartwout faced off in Weehawken, New Jersey. They fired at least five rounds before their seconds intervened, leaving both men wounded. In this case, the clash had nothing to do with political principle; Clinton and Swartwout were Republicans. It was a patronage squabble that still erupted into gunfire, showing how normalized armed violence was in settling disputes.

Gun culture and its expansion

Bob Grieser/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

It is tempting to dismiss political violence as a leftover from some “primitive” or “frontier” stage of American history, when politicians and their supporters supposedly lacked restraint or higher moral standards. But that is not the case.

From before the Revolution onward, physical punishment or even killing were ways to enforce belonging, to mark the boundary between insiders and outsiders, and to decide who had the right to govern.

Violence has never been a distortion in American politics. It has been one of its recurring features, not an aberration but a persistent force, destructive and yet oddly creative, producing new boundaries and new regimes.

The dynamic only deepened as gun ownership expanded. In the 19th century, industrial arms production and aggressive federal contracts put more weapons into circulation. The rituals of punishing those with the wrong allegiance now found expression in the mass-produced revolver and later in the automatic rifle.

These more modern firearms became not only practical tools of war, crime or self-defense but symbolic objects in their own right. They embodied authority, carried cultural meaning and gave their holders the sense that legitimacy itself could be claimed at the barrel of a gun.

That’s why the phrase “This isn’t who we are” rings false. Political violence has always been part of America’s story, not a passing anomaly, and not an episode.

To deny it is to leave Americans defenseless against it. Only by facing this history head-on can Americans begin to imagine a politics not defined by the gun.

![]()

Maurizio Valsania does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Yes, this is who we are: America’s 250-year history of political violence – https://theconversation.com/yes-this-is-who-we-are-americas-250-year-history-of-political-violence-265171