Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Sasha Grishin, Adjunct Professor of Art History, Australian National University

Vivienne Westwood and Rei Kawakubo are two fashion designers who redefined “the look” of fashion on the street from the 1970s onwards.

They were born a year apart in the early 1940s, one in Derbyshire in England, the other in Tokyo in Japan. They were both largely self-taught, self-made mavericks who contributed to, and redefined, the punk scene in the 60s and 70s. Their use of unconventional materials and designs shocked the fashion establishment and helped to establish alternative realities of accepted dress codes.

The great achievement of many revolutionary National Gallery of Victoria exhibitions is the strategy of juxtaposing two vibrant artistic personalities, whereby a new and unexpected reality is created that allows us to establish a fresh perspective.

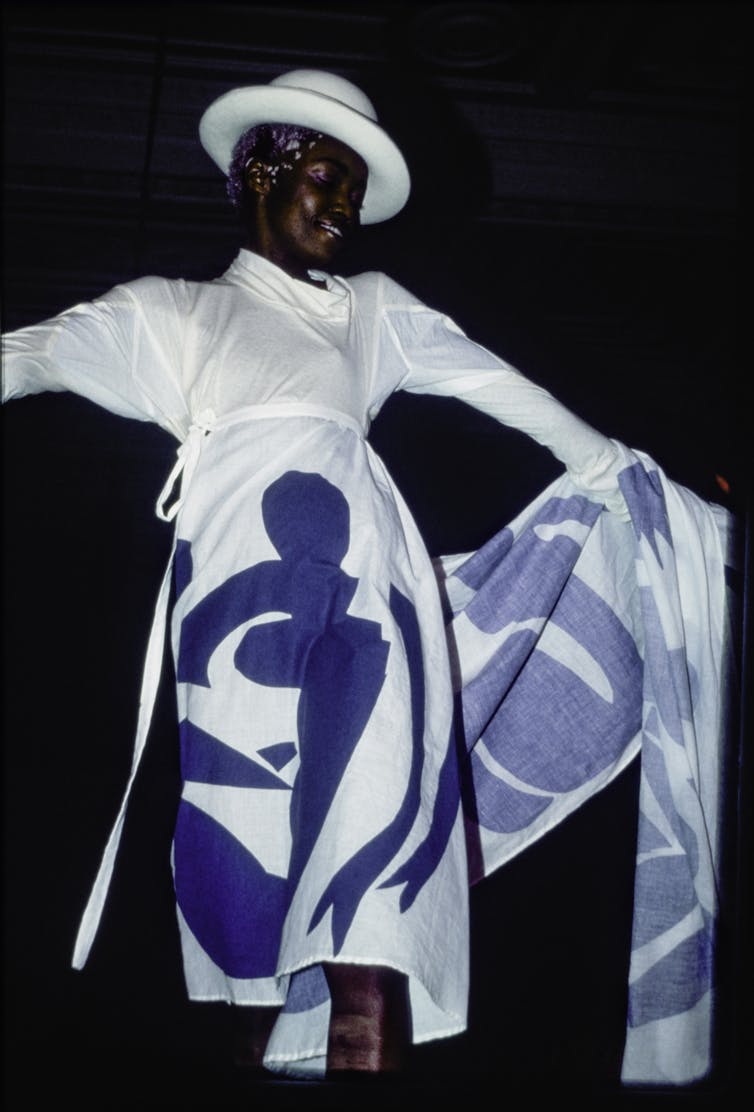

Photo © Robyn Beeche

Westwood and Kawakubo are household names in the fashion industry. But by bringing them together and clustering their works under five thematic categories, new insights appear.

It is a spectacular selection of over 140 key and signature pieces drawn from the growing holdings of the NGV supplemented with strategic loans from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; The Victoria & Albert Museum, London; Palais Galliera, Paris; the Vivienne Westwood archive; and the National Gallery of Australia, among others.

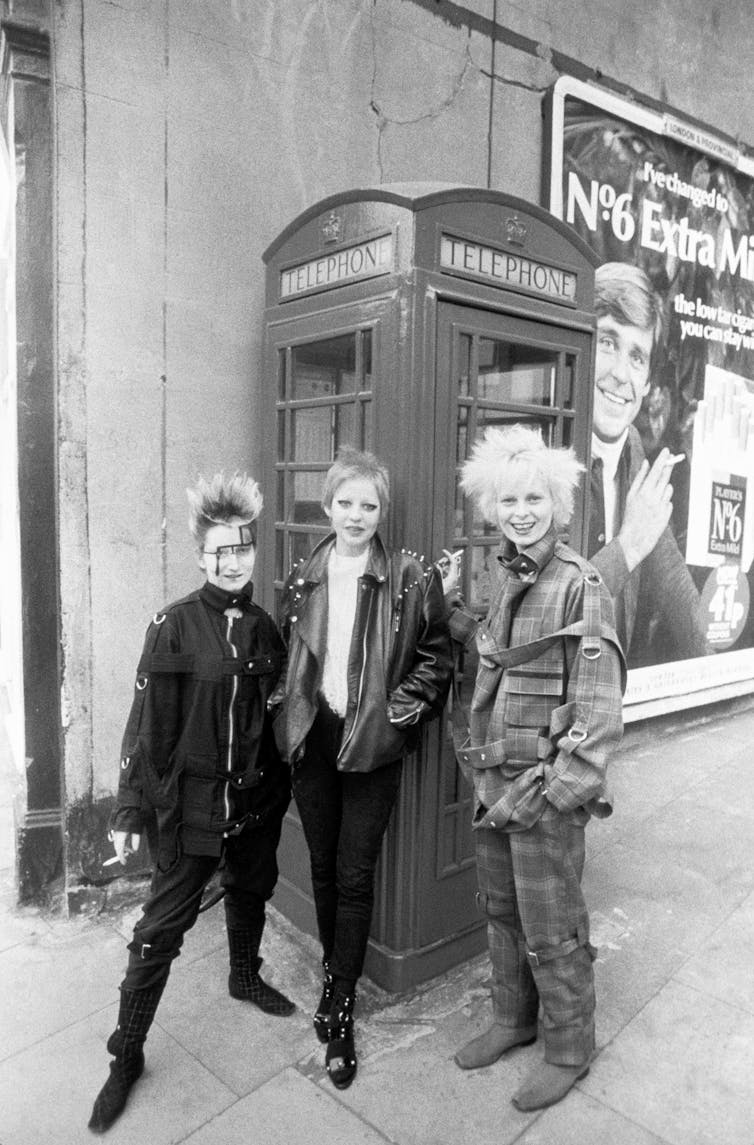

Punk and provocation

Westwood, subsequently Dame Vivienne Isabel Westwood, initially in collaboration with Malcolm McLaren of Sex Pistols fame, helped to mould and dress the London punk scene.

For her, dress was never ideologically neutral but a lightning rod for social change.

Photo © Tim Jenkins / WWD / Penske Media via Getty Images

Pornographic slogans, emblems anchored in fetish practices and sadomasochism, and dresses made of plastics and supplemented with safety pins and chains subverted the comfortable status quo and allowed her fashion sense to penetrate into the middle classes.

What was once outrageous became something daringly respectable.

Kawakubo was born into an academic family and came to fashion design when making her own clothing in the 1960s under the label Comme des Garçons (“like the boys”) in Tokyo.

Conceived as anti-fashion, sober and severe, she made largely monochrome garments – black, dark grey and white – for women, with frayed, unfinished edges, holes and asymmetric shapes.

A men’s line was added in 1978. The number of outlets in Japan grew into the hundreds. Later, her designs established a strong presence in Paris.

The themes that bring the two fashion designers together in this exhibition include the opening section, Punk and Provocation. Both designers drew on the ethos of punk with its desire for change and the rejection of old ways.

Breaking orthodoxies

A second section is termed Rupture for the conscious desire to break with convention, whether it be Westwood’s Nostalgia of Mud collection of 1983 or Kawakubo’s Not Making Clothes collection of 2014.

There is a strongly expressed desire to break with the prevailing orthodoxies.

Photo © Robyn Beeche

A third section, Reinvention, hints at a postmodernist predilection of both artists to delve into traditions of art history and from unexpected sources, such as Rococo paintings, revive elements from tailoring traditions, ruffles and frills.

Although both artists are rule breakers, they do not act from a position of ignorance. It is from a detailed, and at times pedantic, knowledge of garments from the past.

Image © Comme des Garçons. Model: Mirre Sonders

In the late 1980s, Westwood revived English tweeds and Scottish tartans. Kawakubo drew on the basics of traditional tailoring in menswear and applied it to unorthodox patterns and materials in her garments for women.

The ‘ideal’ body

A fourth section, The Body: Freedom and Restraints, perhaps most problematically challenges the conventions of idealised female beauty and the objectification of the female body.

It is argued in the exhibition that Westwood’s Erotic Zones collection (1995), and Kawakubo’s The Future of Silhouette (2017–18), may be viewed as attempts to redefine the female body.

Photo © James Devaney / WireImage via Getty Images

Kawakubo’s Body meets dress-Dress meets body collection, presented in 1996, systematically interrogates boundaries between bodies and garments. Westwood, at a similar time, played with padding and compression in her designs to question the ideals of a sexual, “ideal” body.

The final section of the exhibition is appropriately termed The Power of Clothes. This returns us to the recurring theme of employing fashion to make a statement concerning social change, whether this be the punk revolution or protests connected with climate change.

Courtesy of Vivienne Westwood Heritage. Photo: Sean Fennessy

Through their work, both Westwood and Kawakubo argue fashion is a political act and make broader social statements through their garments, particularly women’s wear.

Both fashion designers were prominent polemicists. As quoted in the exhibition, Westwood in 2011 declared,

I can use fashion as a medium to express my ideas to fight for a better world.

Kawakubo is quoted as saying in 2016,

Society needs something new, something with the power to provide stimulus and the drive to move us forward […] Maybe fashion alone is not enough to change our world, but I consider it my mission to keep pushing and to continue to propose new ideas.

This exhibition will be seen as historically significant and it is accompanied with a weighty catalogue. The NGV has established major collections of over 400 pieces of Westwood’s and Kawakubo’s work that lays the foundation for any further serious exploration of fashion from this period anywhere in the world.

Westwood | Kawakubo is at the National Gallery of Victoria until April 19.

![]()

Sasha Grishin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. How self-taught, self-made mavericks Vivienne Westwood and Rei Kawakubo redefined punk – https://theconversation.com/how-self-taught-self-made-mavericks-vivienne-westwood-and-rei-kawakubo-redefined-punk-269517