Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Jenny Hocking, Emeritus Professor, Monash University

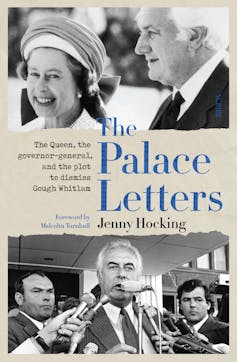

This is an edited extract from The Palace Letters: The Queen, the governor-general, and the plot to dismiss Gough Whitlam by Jenny Hocking.

It was cold, mid-winter in Canberra, when I returned to the National Archives in mid-2019 searching for more documents, scouring through the accession records for Sir John Kerr’s papers, where, I told myself, even the most obscure files might turn up something important, something I had never imagined.

And then, quite suddenly, one of them did.

As I waited for the High Court to consider my application for special leave, a file containing letters between Kerr and the queen’s private secretary after Kerr had left office landed in my inbox.

I had requested this file, with the arresting title “Buckingham Palace”, eight years earlier, after which it had disappeared into the archival limbo of “withheld pending advice”.It suddenly reappeared in a “decision on access” email, with no explanation for the eight-year delay, with its cache of letters providing a jaw-dropping account of royal intervention in Kerr’s autobiography, Matters for Judgment, which was soon to be released.

The supportive exchanges between Kerr, Prince Charles and the queen and [her private secretary, Sir Martin] Charteris, which had been so welcome before the dismissal, soon became a major concern for the palace, which feared losing control of both the increasingly erratic Kerr and their letters.

As the outcry over the dismissal showed no sign of abating even a year later, including demonstrations and angry placards, and paint thrown at the vice-regal Rolls-Royce, pressure was building on Kerr to resign.

Under siege, he began to agitate for the release of the palace letters, which he felt would bolster support for his actions. This began with careless comments about the letters and “the attitude of the Palace” at the time of the dismissal to friends and colleagues.

Word of Kerr’s indiscretion, his boasting of the queen’s approval of “the way that I am going about things”, soon reached the palace itself, to great alarm. It grew to a crescendo soon after Kerr’s resignation as governor-general took effect in December 1977, with his visit to the queen’s new private secretary, Sir Philip Moore, to plead his case for the release of the letters.

Kerr was intent on using the letters to garner support for his action in dismissing Whitlam if he possibly could – and what better place to do it than in his autobiography, which he was finalising in self-imposed exile in England? His book was being eagerly, and in some quarters nervously, awaited, since Kerr was loudly proclaiming that he would now report “the facts of the happenings of 1975 […] in the interests of truth”.

With publication looming, and with it the prospect that Kerr might reveal their secret discussions, the queen’s private secretary contacted Kerr directly and asked for a copy of his draft manuscript.

“Buckingham Palace has evinced an interest in the manuscript and all parts of it which touch directly upon the Queen’s position and the Palace’s position will need to be thought about,” Kerr wrote to his lawyers in Sydney. Kerr dutifully sent his manuscript to the queen’s private secretary, and it was soon “in safe keeping now at Buckingham Palace”.

“It will make fascinating reading,” Moore assured him, “I will get into [sic] touch with you again as soon as I have finished it.”

Moore’s brief comment on the book arrived three weeks later, and if you thought the historical dissembling about the dismissal must eventually reach a natural end, think again.

The queen’s private secretary thanked Kerr for excising any references to his discussions with Charteris about “the controversy”:

I am grateful to you for being so scrupulous in omitting any reference to the informal exchanges which you had with Martin Charteris. I know that you have throughout been anxious to keep The Queen out of the controversy and I much appreciate the way in which you have achieved this in the book.

Which shows Kerr to be as unreliable in print as he was in office.

Kerr could scarcely hide his delight at this royal approbation of his expurgated history:

I did my very best of course to omit any reference to the exchanges between Martin Charteris and myself. It is particularly gratifying to me to know that the result is satisfactory.

These letters not only confirm Kerr was in contact with Charteris regarding the dismissal, but they also reveal that the palace and Kerr then agreed to keep these “exchanges” hidden by omitting any mention of them in Kerr’s “autobiography”.

Matters for Judgment duly contained no mention of his “informal exchanges” with Charteris, nor any details of Charteris’s “illuminating observations” and “advice to me on dismissal” that Kerr had noted in his journal.

Despite Kerr’s claims his book would present “the truth” and “facts” about the events of November 1975, it was a tawdry exercise in historical distortion by omission – a royal whitewash of history.

Most shocking in this latest revelation of ongoing royal intrigue was the clear example it provided of the mechanism through which the secrecy that drove the dismissal – the collusion of Kerr with others, and his deception of the prime minister – continued in the construction of its history. It shows the involvement of the palace in the construction of a flawed and filtered history about one of the most contentious episodes in Australia’s history.

It was a shameful episode in that shared history, the details of which were still emerging.

Read more: ‘Palace letters’ reveal the palace’s fingerprints on the dismissal of the Whitlam government

– ref. Book extract – The Palace Letters: the Queen, the governor-general, and the plot to dismiss Gough Whitlam – https://theconversation.com/book-extract-the-palace-letters-the-queen-the-governor-general-and-the-plot-to-dismiss-gough-whitlam-148439