Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Piers Kelly, Linguistic anthropologist, University of New England

This week, newly appointed Greens senator Lidia Thorpe entered the chamber with one fist raised. In her other hand, she carried a large message stick with 441 carefully painted marks.

The lines represented each of the First Nations people who have died under police supervision since the 1991 Royal Commission into Deaths in Custody. The first Indigenous senator from Victoria, Thorpe is a Gunnai and Gunditjmara woman with a history of fighting for justice on behalf of Aboriginal people.

Last year, Alwyn Doolan, a Gooreng Gooreng and Wakka Wakka man (and co-author of this article) brought three message sticks to deliver to the Prime Minister representing Creation, Colonisation and Healing.

He carried them to Canberra all the way from Cape York, walking the long way round via Tasmania and Melbourne in a journey of over 8,500 kilometres. His intention was to submit a tribal law notice to the Australian government, to declare First Nations sovereignty, and open a new dialogue with the First Nations of this land.

These two events continue a powerful pre-Invasion tradition, when message sticks were sent between distant communities to maintain diplomatic relations.Treacherous journeys

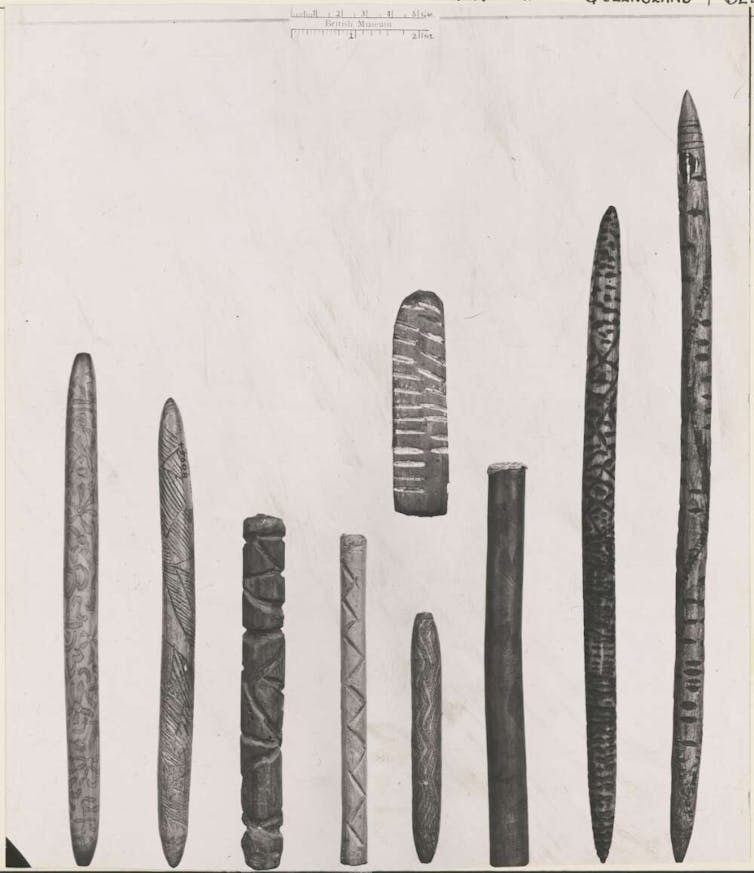

Traditionally, the Nation sending the message would appoint an individual to serve as a messenger to travel vast distances across land or water to meet a recipient. The sticks were small enough to carry a long way. Many of the signs on the stick had fixed meanings while others were intended to be decorative.

Colours such as red ochre or white pipe-clay also added meaning, and even the type of timber had significance. Along with the message, they might also tell a story of where the messenger had come from, depicting the journey as a map.

When the messenger made contact with the intended recipient, they would deliver the message verbally, referring to the signs on the stick to both illustrate and emphasise a memorised oral statement.

Messengers were often men but in some regions women were known to take on this role. If you were a messenger you had a huge responsibility for your own people, and those from other nations were obliged to recognise you as an ambassador, to look after you and guarantee a safe passage.

Message sticks could be on any topic, but what they always had in common was the fact they demanded acknowledgement and mutual respect. They were often announcements about ceremonies, such as initiations or funerals. They could also be for establishing political partnerships, requesting emergency assistance, declaring war, organising hunting, or trading vital resources.

Read more: Friday essay: lessons from stone – Indigenous thinking and the Law

Messengers would set out on foot, sometimes journeying for days or weeks on end. The mission was dangerous. There are over 500 First Nations within Australia and crossing into a foreign territory without permission could be punishable by death. But envoys had diplomatic immunity and their message stick was a bit like a passport in the modern sense.

In order to show peaceful intentions, they displayed the message stick clearly from a safe distance. A common technique was to hang it from the tip of a spear or to tuck it into a headband. Body paint could also be used to signal a special status.

Some past anthropologists held that only “civilised” nations could be seen to possess writing, so downplayed the value of message sticks as communication. Others saw them as precursors to alphabetic script or letters.

Message sticks have even been sent through the mail service. During the second world war, an Indigenous soldier sent a message stick home to his family through the military post, once it had been approved by a mystified government censor.

Carrying meaning

Australia’s First Nations have always been connected through shared kinship systems, histories, Dreamings, values and symbols. This is why the signs on message sticks frequently depict common points of reference with rich cultural associations — like landscapes, totemic animals, and ceremonial grounds — that wouldn’t require explanation.

As Indigenous people began to encounter new phenomena like ships, livestock and homesteads these were symbolised on message sticks. Individuals had signatures to guarantee the message came from them and would be addressed to the correct person.

Shared understandings helped ensure a message could be correctly interpreted, even when a messenger was not available to explain it.

In some places, white settlers learned from First Nations peoples how to make message sticks and used them to facilitate diplomatic communications with communities.

Read more: New coins celebrate Indigenous astronomy, the stars, and the dark spaces between them

Political messages

During the period of colonial dispossession, First Nations people have introduced adaptations and innovations. They began to make use of non-native timbers and took advantage of iron tools.

Message sticks also began featuring Western symbols. Alphabet letters, playing card suits and police insignias have been used sparingly. And from the middle of the 20th century, Indigenous envoys began to bring message sticks to government leaders.

In 1951, Indigenous men sent a message stick to Robert Menzies to solidify an alliance between the Tiwi islands and Canberra. Gough Whitlam received one in 1974 demanding land rights, and Bob Hawke was given one in 1983.

Yolŋu leaders gave Prince Charles a message stick in 2018 during his visit to Yirrkala, asking him to intervene in Treaty negotiations.

When Alwyn Doolan brought his message sticks to Scott Morrison last year — after a gruelling journey — the Prime Minister defied precedent by declining to meet with him.

– ref. What are message sticks? Senator Lidia Thorpe continues a long and powerful diplomatic tradition – https://theconversation.com/what-are-message-sticks-senator-lidia-thorpe-continues-a-long-and-powerful-diplomatic-tradition-147674