Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Iain Lawrie, PhD Candidate, University of Melbourne

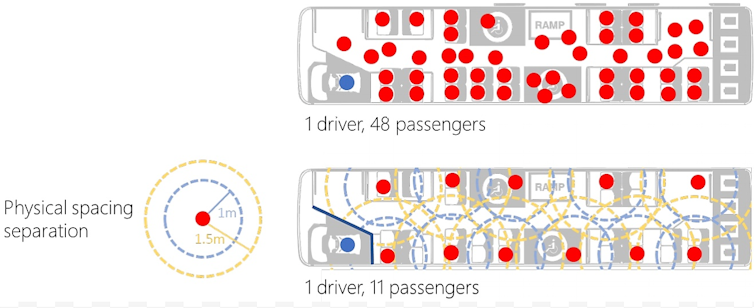

As we re-open our economy and workers gradually return to workplaces, overall travel will increase. However, the need to maintain social distancing means public transport can’t operate at usual capacity. And fears of crowded public transport will lead to commuters making a much higher proportion of trips in private vehicles – unless they are offered viable alternatives such as the ones we discuss here.

Our initial analysis (as yet unpublished) of Australia’s major cities suggests a shift to cars will produce severe traffic congestion if even a modest proportion of the workforce returns to their usual workplaces during the COVID-19 recovery. In this article, we suggest some public transport solutions to avoid congestion caused by a shift to car travel.

Read more: Coronavirus recovery: public transport is key to avoid repeating old and unsustainable mistakes

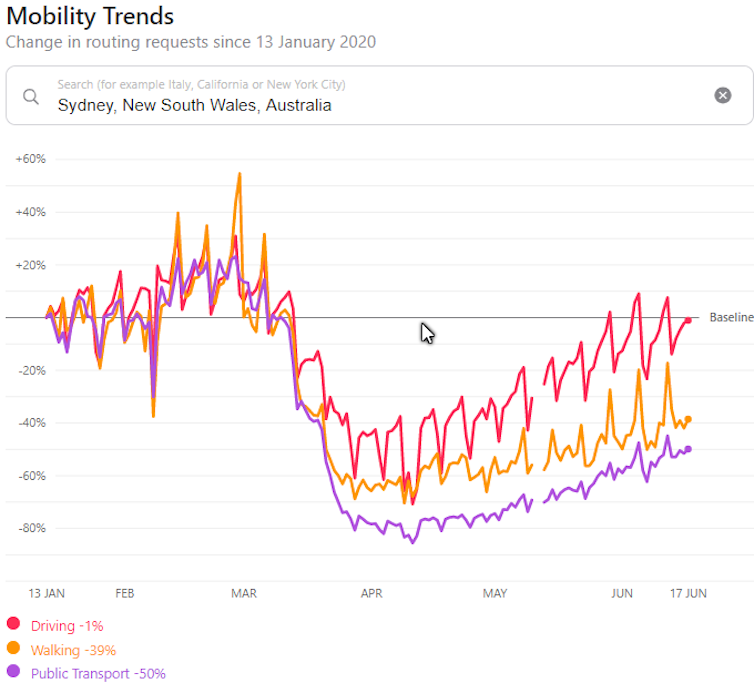

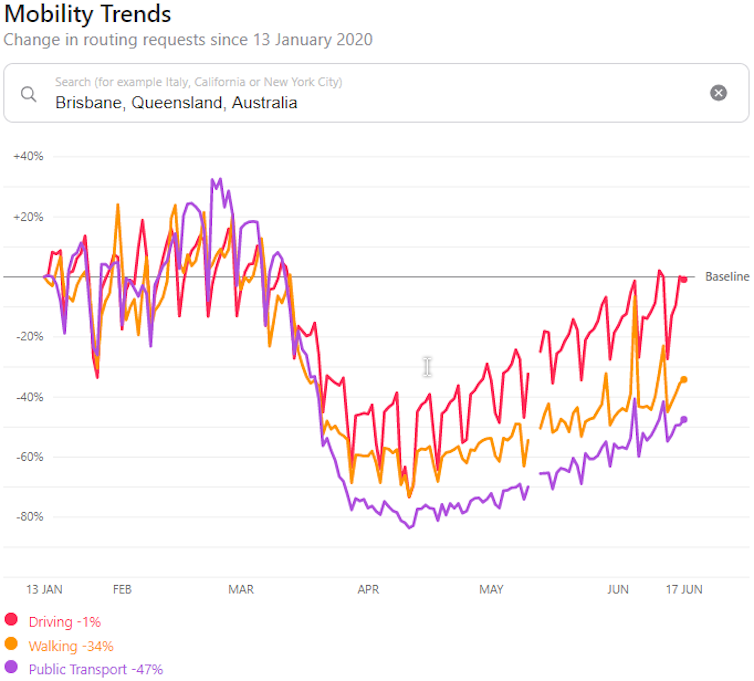

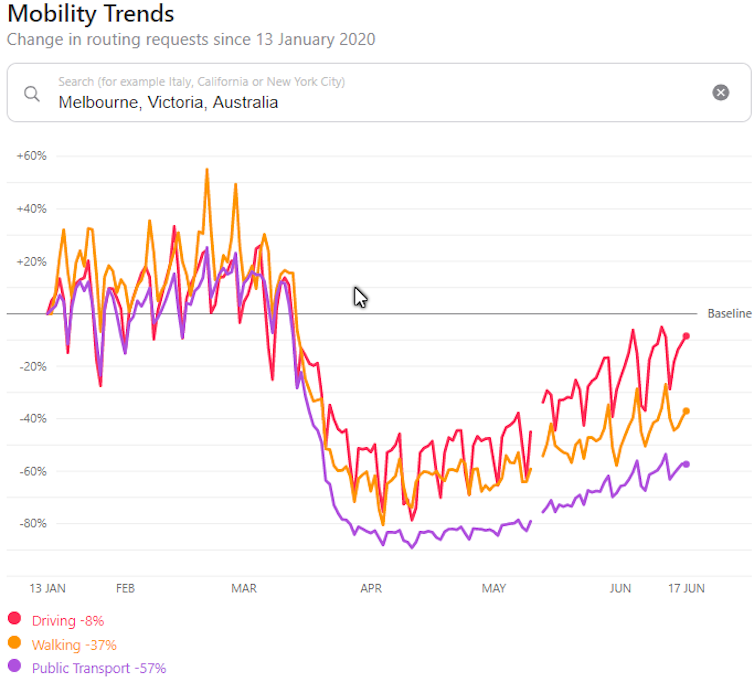

Globally, this trajectory is already becoming apparent. As lockdowns are eased, car use is rising much more quickly than public transport use. The latest figures from cities as diverse as Berlin, Los Angeles, Chicago, Auckland and Sydney all show this.

What are the implications of this trend?

First, the shift to private vehicles will be a bigger problem in cities with centres traditionally served by public transport than dispersed, car-dominated regions. Modelling by Vanderbilt University in the US showed an 85% shift of mass transit riders to cars would increase daily commute times by over sixty minutes in New York, but merely four minutes in Los Angeles. This is because public transport serves a mere 5% of journeys to work in Los Angeles but 56% in New York.In cities that rely heavily on public transport, or even those with car-dominated suburbs but transit-dominated centres such as Sydney and Melbourne, a shift to cars for CBD trips will very quickly overwhelm the capacity of the road network. Pre-pandemic, 71% of trips to the Sydney CBD and 63% to Melbourne’s CBD were on public transport. So, while travel volumes may remain well below pre-pandemic levels for some time, road traffic is recovering faster than other travel modes.

Sydney’s and Brisbane’s road traffic volumes have already returned largely to pre-pandemic levels even while most CBD offices remain empty. Melbourne isn’t far behind. Returning commuters are in for a shock.

What can we do about it?

Several commentators suggest now may be the time to apply congestion pricing – charging a fee to use roads in peak periods. However, when many people are making travel decisions based on the health risks, such policy may not produce the desired behaviour change.

Read more: How ‘gamification’ can make transport systems and choices work better for us

The alternative is to improve commuters’ public transport options, rather than trying to price congestion away. The aim should be to allow it to operate more effectively while still providing room for on-board social distancing.

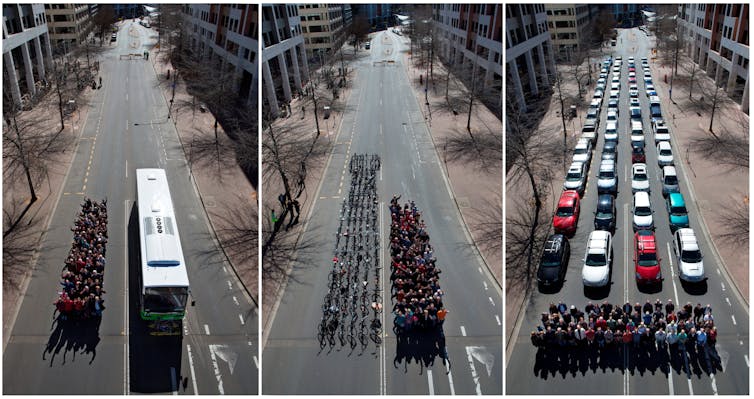

This is no easy task, yet it may be politically and technically easier than rapidly bringing in a comprehensive road-pricing regime. Even with social distancing restrictions, public transport will use roads more efficiently than private cars.

The return to work must be gradual and supported by considerable flexibility in working hours. This will help manage peak demands. But on its own it’s not enough if frequent public transport services continue to be offered only during a limited commuter peak.

More services, more often

So, public transport services need to run at high frequencies for many more hours in the day. Some analysts suggest services be run at peak frequencies for most of the day.

Many suburban bus services, particularly direct services along arterial roads, should run much more often than their existing peak offerings. Routes can be tweaked to remove unnecessary detours that lead to slow travel times.

Read more: 1 million rides and counting: on-demand services bring public transport to the suburbs

These frequent, direct services should be supported by rigorous cleaning, visual guidance to maintain separation on platforms and within vehicles, and tools to help identify crowded vehicles.

Most importantly, we need to rapidly create “pop-up” dedicated bus lanes right across metropolitan areas. These lanes allow buses to avoid being held up by increasing traffic volumes. Although bus lanes may reduce capacity for private vehicles, when buses run frequently they are a much more efficient use of scarce road space.

Faster travel times for public transport would, in turn, mean operators could deliver more frequent services with existing fleets and drivers. This would reduce the operational cost of allowing for social distancing.

Read more: To limit coronavirus risks on public transport, here’s what we can learn from efforts overseas

Frequent services on these pop-up corridors will provide a critical, time-competitive alternative to driving. Although not without its challenges, implementing a fast and frequent bus network is conceptually straightforward and the cost is modest compared to the congestion impacts it could offset.

This solution will require a nimble and co-operative approach from state and local transport authorities and private operators. Success will mean our transit-centred CBDs and district centres continue to function efficiently.

In the longer term, a fast and frequent metropolitan transit network will leave a lasting positive legacy, supporting carbon reduction and city-shaping investments such as Sydney’s Metro and Brisbane’s Cross River Rail. Failure will lead to crippling congestion that erodes the economic and social strength of our previously vibrant cities.

– ref. How to avoid cars clogging our cities during coronavirus recovery – https://theconversation.com/how-to-avoid-cars-clogging-our-cities-during-coronavirus-recovery-140744