Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Luke Jeffrey, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Southern Cross University

We all know trees are climate heroes. They pull carbon dioxide out of the air, release the oxygen we breathe, and help combat climate change.

Now, for the first time, our research has uncovered the hidden world of the tiny organisms living in the bark of trees. We discovered they are quietly helping to purify the air we breathe and remove greenhouse gases.

These microbes “eat”, or use, gases like methane and carbon monoxide for energy and survival. Most significantly, they also remove hydrogen, which has a role in super-charging climate change.

What we discovered has changed how we think about trees. Bark was long assumed to be largely biologically inert in relation to climate. But our findings show it hosts active microbial communities that influence key atmospheric gases. This means trees affect the climate in more ways than we previously realised.

Luke Jeffrey, CC BY-ND

Teeming with life

Over the past five years, collaborative research between Southern Cross and Monash universities studied the bark of eight common Australian tree species. These included forest trees such as wetland paperbarks and upland eucalypts. We found the trees in these contrasting ecosystems all shared one thing in common: their bark was teeming with microscopic life.

We estimate a single square metre of bark can hold up to 6 trillion microbial cells. That’s roughly the same number of stars in about 60 Milky Way galaxies, all squeezed onto the surface area of a small table.

To find out what these bark microbes were doing, we first used a technique called metagenomic sequencing. In simple terms, this method reads the DNA of every microorganism in a sample at once. If normal DNA sequencing is like reading one book, metagenomics is like scanning an entire library. We pulled out clues about who lived in the bark and which “tools” or enzymes they might have.

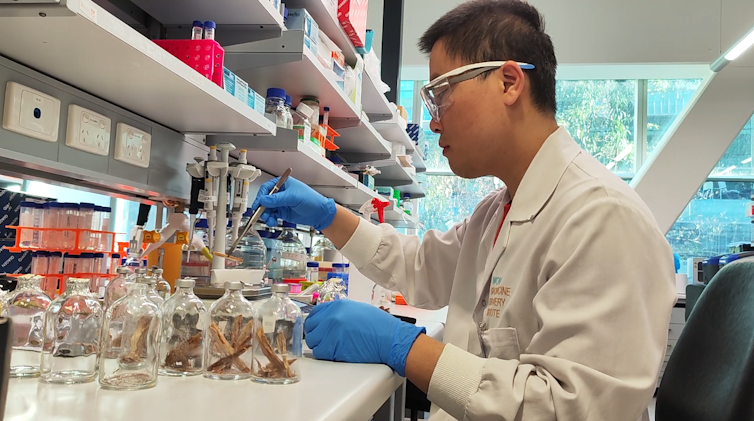

Jialing Zeng, CC BY-ND

A simple analogy is to imagine a construction site where each tradespeople carries different tools. While some tools overlap, many are specific to their trade. If you see a pipe wrench, you can deduce a plumber is around.

In a similar way, metagenomics showed us the “tools” the microbes were carrying in their DNA – genes that let them eat atmospheric gases like methane, hydrogen or carbon monoxide. This gave us valuable insight into what the bark microbes could do.

But, like a construction site, having tools doesn’t mean the “tradies” are using them for jobs all the time. So we also measured the movement of gases in and out of the bark to see which microbial “jobs” were happening in real time.

Luke Jeffrey, CC BY-ND

Bark microbes eat gases

Many of the microbes living in bark can live off various gases. This is a process recently coined as “aerotrophy”, as in “air eaters”. Some of their favourite gases include methane, hydrogen and carbon monoxide, all of which affect the climate and the quality of the air we breath.

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, responsible for about one third of human-induced warming. We found most wetland trees contained specialist bacteria called methanotrophs, that eat methane from within the tree.

We also saw abundant microbial enzymes that remove carbon monoxide, a toxic gas for both humans and animals. This suggests tree bark helps clean the air we breathe. This could be particularly useful in urban forests, as cities often have elevated levels of this harmful and odourless gas.

But one finding stood out above all others. Within every tree species examined, in every forest type, and at every stem height, bark microbes consistently removed hydrogen from the air. In other words, trees could be a major, previously unrecognised, global natural system for drawing down hydrogen out of the atmosphere.

Luke Jeffrey, CC BY-ND

Global possibilities

When we scaled up what these microbes were doing across all trees globally, the potential impact becomes striking. There are about 3 trillion trees on Earth, and together their bark has a huge cumulative surface area, rivalling that of the entire land surface of the planet.

Taking this into account, our calculation suggests that tree-microbes could remove as much as 55 million tonnes of hydrogen from the atmosphere each year.

Why does this matter? Hydrogen affects our atmosphere in ways that influence the lifetime of other greenhouse gases – especially methane. In fact, hydrogen emissions may be “supercharging” the warming impact of methane.

By using a simple model, the annual amount of hydrogen removed by bark microbes may indirectly offset up to 15% of annual methane emissions caused by humans.

In other words, if tree bark microbes weren’t doing this work, there would be more methane in the atmosphere, and our rising methane problem could be even bigger.

This also hints at another exciting possibility: planting trees could expand this microbial atmosphere-cleaning potential, giving microbes more surface area to apply their trade and help remove even more climate damaging gases from the air.

The ‘barkosphere’

Our research points to many exciting new possibilities and uncertainties around the previously hidden role of a tree’s “barkosphere”.

We want to know which tree species host the most active “gas-eating” microbes, which forests remove the most methane, carbon monoxide or hydrogen, and how climate change may alter these communities and their activities.

This knowledge could help guide future reforestation, conservation, carbon accounting strategies. It may even change the way we try and limit climate change.

Trees have always regulated our climate. But now we know their bark – and the hard working microscopic ecosystems living inside – may be far more important than previously thought.

Luke Jeffrey, CC BY-ND

![]()

Luke Jeffrey receives funding from the Australian Research Council through an ARC DECRA Fellowship.

Chris Greening receives funding from the Australian Research Council, National Health & Medical Research Council, Australian Antarctic Division, Human Frontier Science Program, and Wellcome Trust.

Damien Maher receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Pok Man Leung receives funding from the Australian Research Council through an ARC DECRA Fellowship.

– ref. We discovered microbes in bark ‘eat’ climate gases. This will change the way we think about trees – https://theconversation.com/we-discovered-microbes-in-bark-eat-climate-gases-this-will-change-the-way-we-think-about-trees-269612