Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By John Buchanan, Professor, Discipline of Business Information Systems, University of Sydney Business School, University of Sydney

Mick Tsikas/AAP

The Albanese government’s plan to improve the pathway to permanency for casual workers has employers worried, fearful their ability to employ casual workers will be restricted.

Even before the details had been released, there was certainty, in the words of Australian Industry Group chief executive Innes Willox, that there “is simply no justification for further changes to the regulation of casual work”.

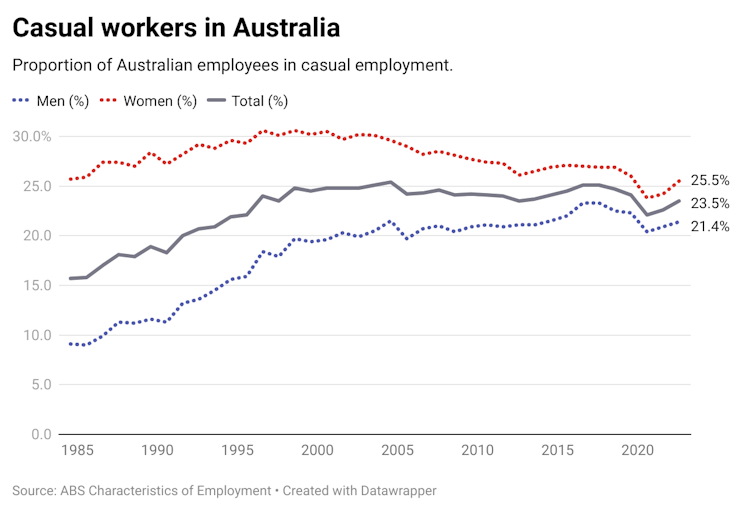

In support of this argument are statistics suggesting the casualisation trend has peaked. But that’s by no means certain: the most recent data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics shows casualisation climbing again, with an overall rate of 23.5%.

The counterargument is that entrenched casualisation doesn’t make the status quo right, and that the government’s proposed reforms will give greater recognition to reality. That is, if a worker is effectively working as permanent employee, they have the right to be treated as such.

Read more:

Albanese government to make it easier for casuals to become permanent employees

Rise of the ‘permanent casual’

While casual employment can often suit both employer and employee, the evidence does suggest some employers have exploited the legal ambiguities around definitions and obligations.

Australia’s National Employment Standards – the minimum safety net for all workers – say a casual employee who has worked for their employer for 12 months must be offered the option to convert to full-time or part-time (permanent) employment. But there are significant exemptions, particularly for small business.

Close to 60% of Australia’s casual workers have been with their employer for more than a year, and 45% to 60% report regular hours and pay. This has resulted in the great Australian oxymoron of “the permanent casual”.

There is effectively a class of workers who don’t get holiday and sick pay, no matter how long or regularly they work, simply because their employer deemed them “casual” when they began.

Read more:

The truth about much ‘casual’ work: it’s really about permanent insecurity

The legal landscape

Since the 1990s, workers and their union representatives have challenged these contrivances in industrial tribunals. Several of these decisions have been tested on appeal in the Federal Court.

In two cases in 2018 and 2020, the Federal Court agreed a worker’s employment status should based on the reality of their long-term employment relationship. That is, if there was continuity, based on extended, regular patterns of employment, a worker was a permanent employee. Similar principles applied to those deemed contractors.

However, appeals to the High Court in 2021 and in 2022 overturned these rulings. For the High Court, a formal stipulation of relations written in a contract were all that counted. The reality of life on the job was irrelevant.

Common law versus parliament

The High Court’s decisions – that formal freedom of contract has to be respected irrespective of the realities of bargaining power – reflect a long struggle between the common law and parliament in matters concerning working life.

In the 1700s and 1800s, workers were jailed for meeting to discuss wage campaigns. To this day, commercial common law considers the principle of “freedom of contract” as the foundation for all commercial relations – including those involving employment. Union activity is an illegal restraint of trade.

These principles have never been changed in the courts. It is only by statute (legislation passed by parliament) that trade unions and collective action by workers has been allowed.

The federal Employment and Workplace Relations Minister, Tony Burke, says the government “will legislate a fair, objective definition to determine when an employee can be classified as casual”, and no one will lose their casual status if that is their preference.

There will, no doubt, be opposition, with warnings about threats to productivity and suggestions economic conditions are too fragile.

But there’s a lot to be said in favour of giving greater recognition to reality.

![]()

John Buchanan has been applied research based in the university sector for over 30 years. During this time he as undertaken applied research projects for governments of all persuasions, unions, NGOs and employers. His most recent projects have been for the former NSW Government, its workers’ compensation authority (iCare) and the Queensland Nurses and Midwives Union. He is a member of the National Tertiary Education Union. From June 2021 until June 2023 he was a member of the NTEU Bargaining Team that recently settled the University of Sydney Enterprise Agreement. A key feature of that agreement concerns reducing casual academic employment by 20% and increasing the number of full time, continuing roles by 330 positions over the period 2023 – 2026.

– ref. Employers will resist, but the changes for casual workers are about accepting reality – https://theconversation.com/employers-will-resist-but-the-changes-for-casual-workers-are-about-accepting-reality-210272