Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Robyn J. Whitaker, Associate Professor, New Testament, Pilgrim Theological College, University of Divinity

The cross, or crucifix, is arguably the central image of Christianity.

What’s the difference between the two? A cross is just that – an empty cross. It stands as a statement that Jesus is no longer on the cross and thus symbolises his resurrection.

A crucifix, on the other hand, includes the body of Jesus, to more vividly remind viewers of his death.

Many contemporary Christians, from bishops to ordinary folk, wear some kind of cross or crucifix around their neck and it would be rare to find a church that did not have at least one prominently displayed in the building.

While a symbol of faith, it is not just the pious who wear crosses. Madonna famously wore crucifix earrings and necklaces constantly throughout the 1980s and ‘90s. She is quoted as doing so because she provocatively “thought Jesus was sexy”.

The recent ubiquity of the cross as a fashion item means it is sold at everything from cheap tween fashion stores to that jeweller renowned for its little turquoise boxes, where a diamond cross necklace can run in excess of $10,000.

The 2018 Met Gala’s theme, Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and Catholic Imagination, further bestowed religious imagery with fashion icon status by making it central to one of the fashion industry’s key events.

Yet the cross was not always the dominant symbol of Christianity that it is now, and would certainly not have been worn as a fashion accessory by early Christians.

In fact, it took centuries for Christians to begin to depict the cross in their art.

Read more:

Jesus wasn’t white: he was a brown-skinned, Middle Eastern Jew. Here’s why that matters

An undignified death

While some want to credit Emperor Constantine for the use of the cross as becoming more widespread after the 4th century, it is not that simple. Part of the answer lies in the nature of crucifixion itself.

While crucifixion included some variety in antiquity, it was typically a form of execution reserved for non-elite, non-citizens in the 1st-century Roman Empire.

Slaves, the poor, criminals and political protesters were crucified in their thousands for “crimes” we might today consider minor offences. The types of cross structures might differ, but as a form of execution, crucifixion was brutal and violent, designed to publicly shame the victim by displaying him or her naked on a scaffold, thereby asserting Rome’s power over the bodies of the masses.

That Jesus suffered such an undignified death was an embarrassment to some early Christians. The apostle Paul describes Jesus’ crucifixion as a “stumbling block” or “scandal” to other Jews. Others would imbue it with sacrificial meaning to make sense of how the one claimed as God’s Son would suffer in this way. But the shame associated with this kind of death remained.

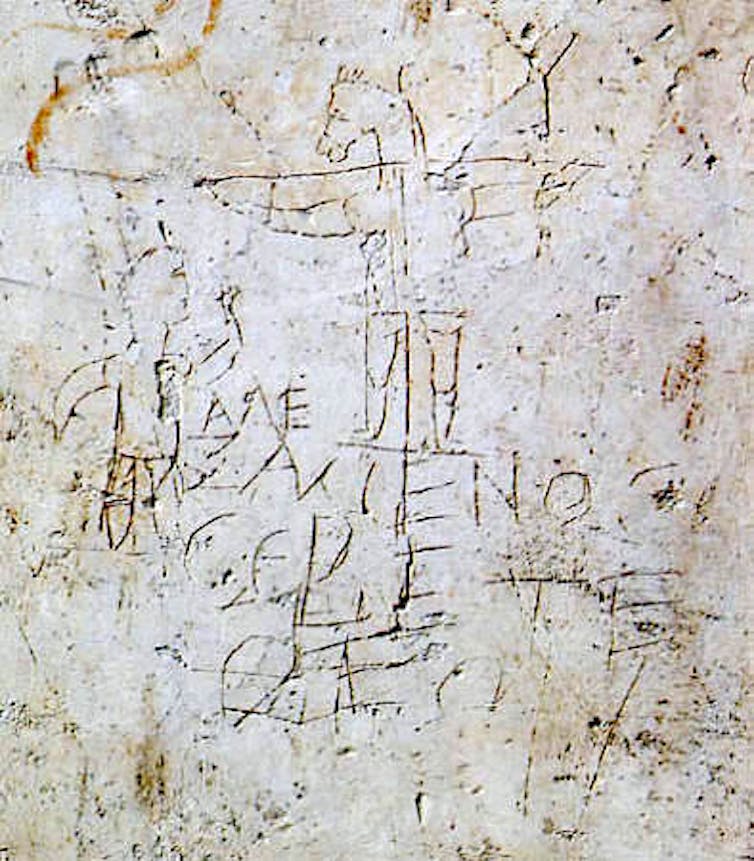

Wikimedia Commons

A now infamous piece of graffito, dating to the early 3rd century in Rome, arguably mocks Jesus’ manner of death. Sketched on a wall in Rome, the Alexamenos graffito portrays a donkey-headed male figure on a cross under which is written “Alexamenos, worship god”. The suggestion is that the parody was directed at Christians precisely because they worshipped a man who had died by crucifixion.

Christian images

Felicity Harley-McGowan, an expert on crucifixion and early Christian art, argues Christians began to experiment with making their own specifically Christian images around 200 CE, roughly 100-150 years after they began writing about Jesus.

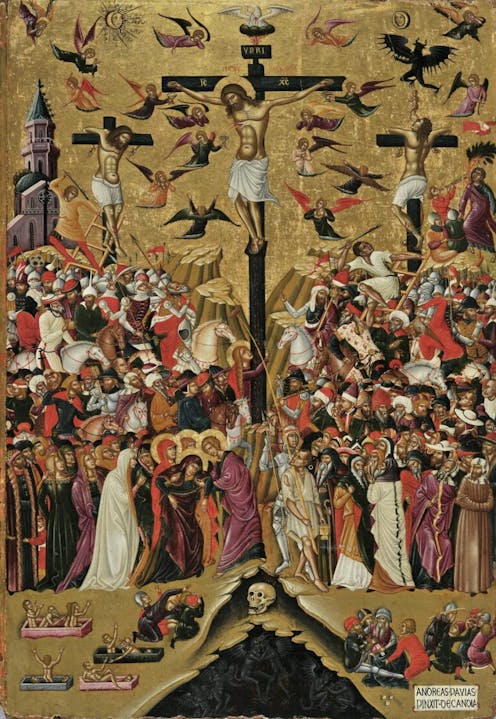

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

The slowness to depict Jesus on a cross was not about a general sensibility to the visual arts, although they do seem to have been very selective in what they did portray. Artwork typically depicted biblical stories and used bucolic imagery to show others being rescued from death or to tell the stories of biblical heroes like Daniel or Abraham.

In the 4th century, Christians began to depict other death scenes from the Bible, such as the raising of Jairus’ daughter, but still not Jesus’ death. Harley-McGowan writes:

it is clear that the earliest representations of deaths in early Christian art were pointed in their focus on actions after the event.

Such depictions emphasised healing, new life and resurrection from death. This emphasis is one explanation for why Christians were slow to depict Jesus’ actual death.

One of the earliest extant depictions of Jesus can be found in the Maskell Passion Ivories dating to the early 5th century CE, more than 400 years after his death. These ivories formed a casket panel that includes one death scene amid a range of scenes telling the Jesus story.

© The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA

Like much previous Christian art, the emphasis remained on Jesus’ victory over death rather than any desire to depict the reality or violence of his crucifixion. One way to show this was to portray Jesus on a cross but with his eyes open, alive and undefeated by the cross; in the Maskell Ivory, Jesus’ alertness is contrasted with the clearly dead Judas.

While there is a 3rd-century magical amulet that includes crucifixion imagery (and there may have been other gems and amulets lost to history that associated his resurrection from death in magical terms), depictions of the cross only began to emerge in the 5th century and would remain rare until the 6th.

© The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA

As churches began to be built, crucifixes appeared on engraved church doors and would remain the more standard image until the Reformation emphasis on the empty cross.

The cross continues to have a complex history, being used as both a symbol of Christian ecclesial power and of white supremacy by groups like the Ku Klux Klan.

There can be beauty, intrigue, magic and terror in these cross traditions.

© The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA

On one hand, it stands as a symbol of Christian belief in Jesus’ death and resurrection. On the other, it is a reminder of the violence of the state and capital punishment.

Perhaps, 2,000 years later, it is always both – even when diamond-encrusted.

Read more:

Baby Jesus in art and the long tradition of depicting Christ as a man-child

![]()

Robyn J. Whitaker does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. The crucifixion gap: why it took hundreds of years for art to depict Jesus dying on the cross – https://theconversation.com/the-crucifixion-gap-why-it-took-hundreds-of-years-for-art-to-depict-jesus-dying-on-the-cross-202348