Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Euan Ritchie, Professor in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, School of Life & Environmental Sciences, Deakin University

Wes Mountain/The Conversation/Shutterstockl

Am I not pretty enough? This article is part of The Conversation’s series introducing you to unloved Australian animals that need our help.

Australia is set to host the 2032 Olympic games in Queensland’s capital Brisbane, captivating an audience of billions. With so many eyes on Australia, the burning question is, of course, what animal(s) should be the official mascot(s) of the games, and why?

Summer Olympics past have featured recognisable animal mascots such as Waldi the daschund (Munich, 1972), Amik the beaver (Montreal, 1976), Misha the bear (Moscow, 1980), Sam the eagle (Los Angeles, 1984) and Hodori the tiger (Seoul, 1988).

Iconic and familiar mammals and birds dominate the list. The trend continued at Sydney’s 2000 games which featured Syd (playtpus), Olly (kookaburra) and Millie (echidna).

But the Brisbane Olympics is a great opportunity to showcase lesser known species, including those with uncertain futures.

Sadly Australia is a world leader in extinctions. Highlighting species many are unfamiliar with, the threats to them and their respective habitats and ecosystems, could help to stimulate increased conservation efforts.

From a “worm” that shoots deadly slime from its head, to a blind marsupial mole that “swims” underground, let’s take a look at three leading candidates (plus 13 special mentions). What makes them so special, and what physical and athletic talents do they possess?

Onychophorans, or velvet worms

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Velvet worms are extraordinary forest and woodland denizens thought to have changed little in roughly 500 million years. Australian velvet worms are often smaller than 5 centimetres and look a bit like a worm-caterpillar mash up. They’re found across Australia and other locations globally.

Their waterproof, velvet-like skin is covered in tiny protusions called papillae, which have tactile and smell-sensitive bristles on the end. Velvet worms possess antennae and Australian species have 14-16 pairs of stumpy “legs”, each with a claw that helps them move across uneven surfaces such as logs and rocks.

Alexander Dudley/Faunaverse

Their colour varies between species, often blue, grey, purple or brown. Many display exquisite, detailed and showy patterns that can include diamonds and stripes – clear X-factor for a potential mascot.

Although velvet worms may be relatively small and, dare I say it, adorable, don’t be fooled. These animals are voracious predators.

They capture unsuspecting prey – other invertebrates – at night by firing sticky slime from glands on their heads. Once the victim is subdued, velvet worms bite their prey and inject saliva that breaks down tissues and liquefies them, ready to be easily sucked out.

Tanya Latty

If this isn’t intimidating enough, one species (Euperipatoides rowelli) lives and hunts in groups, with a social hierarchy under the control of a dominant female who feeds first following a kill.

Despite their formidable abilities, velvet worms are vulnerable to habitat destruction and fragmentation, and a changing climate.

Jalbil (Boyd’s forest dragon)

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Jalbil is found in the rainforests of tropical North Queensland. They are a truly striking lizard – bearing a prominent pointy crest and a line of spikes down the back, distinct conical cheek scales and a resplendent yellow throat (dewlap) which can be erected to signal to each other.

Despite their colourful and ornate appearance, Jalbil can be very hard to spot as they’re perfectly camouflaged with their surroundings. They spend much of their time clinging vertically to tree trunks often at or below human head-height. Some have favourite trees they use more frequently.

If they detect movement, they simply move around the tree trunk to be out of direct view.

Chris Jolly

Reaching lengths of around 50cm, Jalbil mostly eat invertebrates, including ants, beetles, grasshoppers and worms. Males may have access to multiple female mates, and breeding is stimulated by storms at the beginning of the wet season.

While Jalbil are under no immediate threat, their future is uncertain. Jalbil are ectothermic, so unlike mammals and birds (endothermic), they can’t regulate their internal body heat through metabolism. Sunlight is often very patchy and limited below the rainforest canopy, restricting opportunities for basking to warm up.

Instead, Jalbil simply allow their body temperature to conform with the ambient conditions of their environment (thermo-conforming). This means if climate change leads to increased temperatures in the rainforests of Australia’s Wet Tropics, Jalbil may no longer be able to maintain a safe body temperature and large areas of habitat may also become unsuitable.

Itjaritjari and kakarratul (southern and northern marsupial moles)

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

These remarkable subterranean-dwelling marsupials really are in a league of their own. Both moles can fit in the palm of your hand, measuring up to about 150 millimetres and weighing about as much as a lemon (40-70 grams).

What these diminutive mammals lack in size they make up for in digging power – if only digging were an official Olympic sport. In central dunefields, they can dig up to 60 kilometres of tunnel per hectare.

Marsupial moles are covered in fine, silky, creamy-gold fur. They have powerful short arms with long claws, shovels for furious digging. Their back legs also help them push. Instead of creating and living in permanent burrows, they “swim” underground across Australia’s deserts for most of their lives.

The impressive adaptations don’t end there either. They also have ridiculously short but strong, tough-skinned tails that serve as anchors while digging. Females also have a backwards-facing pouch and all have nose shields that protect their nostrils, ensuring sand doesn’t end up where it’s not supposed to.

Due to living underground for most of their lives, many mole mysteries remain regarding their day-to-day lives. Scientists do know they eat a wide range of invertebrates including termites, beetles and ants, and small reptiles such as geckoes.

But while neither species is thought to be in danger of extinction, there are no reliable population estimates across their vast distributions. What’s more, introduced predators (feral cats and foxes) are known to prey upon them. Itjaritjari is listed as vulnerable in the Northern Territory.

And 13 special mentions go to…

With so many amazing wildlife species in Australia, it really is a near impossible task to choose our next mascot. So I also want to give special mentions to the following worthy contenders:

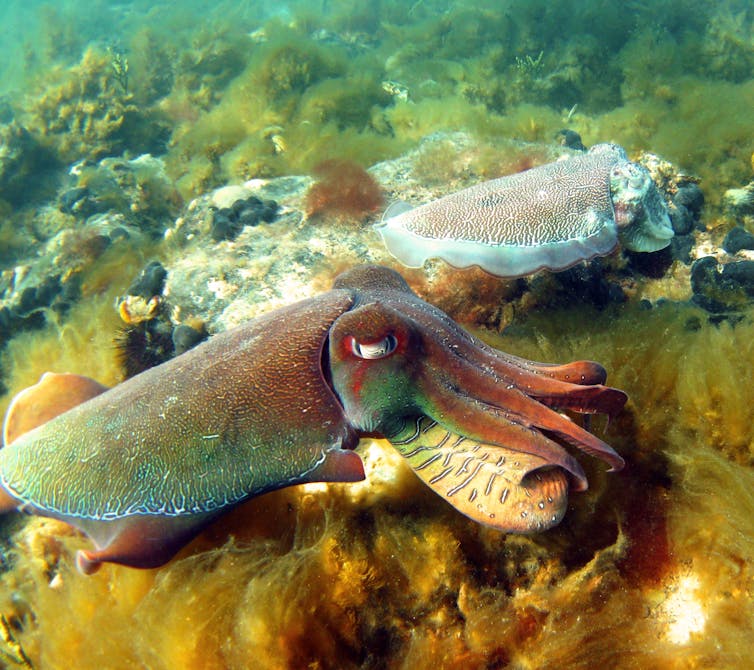

The Australian giant cuttlefish

These marine animals put on spectacular, colourful displays each year when they form large breeding aggregations.

Nick Payne, Author provided

Read more:

Why we’re watching the giant Australian cuttlefish

Arnkerrth (thorny devil)

A desert-dwelling, ant-eating machine that can drink simply by standing in puddles.

Euan Ritchie

The Torresian striped possum

This striking black and white possum is thought to have the largest brain relative to body size of any marsupial. Their extra long fourth finger makes extracting delicious grubs from rotting wood a cinch.

Shutterstock

Kila (palm cockatoo)

Our largest and arguably most spectacular “rockatoo”, which plays the drums.

Shutterstock

Ulysses butterfly

Also known as mountain blue butterflies, the vivid, electric blue wings of Ulysses butterflies can span as much as 130 millimetres.

Willem van Aken/CSIRO Science Image, CC BY-SA

The Australian lungfish

A living fossil, which is now found only in Queensland, can breath air as well as in the water.

Alice Clement

Read more:

Meet 5 remarkably old animals, from a Greenland shark to a featherless, seafaring cockatoo

Mupee, boongary or marbi (Lumholtz’s tree kangaroo)

Despite being powerfully built for climbing, Lumholtz’s tree kangaroos are also adept at jumping, when alarmed they’ve been known to jump from heights of up to 15m to the ground.

Shutterstock

Read more:

Meet Chimbu, the blue-eyed, bear-eared tree kangaroo. Your cuppa can help save his species

The green tree python

Green tree pythons are the most vivid green snake you can possibly imagine. While adult pythons are a vibrant green the juveniles may be bright yellow or red (but not in Australia), changing colour when they are about half a metre long.

Chris Jolly

The chameleon grasshopper

Based on temperature, male chameleon grasshoppers can change colour from black to turquoise, and back to black again, each day.

Kate Umbers

Greater gliders

These fabulous fuzzballs can glide up to 100m in a single leap.

Peacock spiders

Peacock spiders come in rainbow colours and the males sure know how to shake it. Their vivid colours, such as in the species Maratus volans, are due to tiny scales that form nanoscopic lenses created from carbon nanotubes.

Joseph Schubert

Corroboree frogs

They are a striking black and yellow, and desperately need help.

Read more:

Our field cameras melted in the bushfires. When we opened them, the results were startling

And finally, I’ll always have a soft spot for Australia’s much maligned canid, the dingo.

So now, over to you. What are your suggestions for unique animal mascots at the 2032 Brisbane Olympics?

![]()

Euan G. Ritchie is a Councillor within the Biodiversity Council, and a member of the Ecological Society of Australia and the Australian Mammal Society.

– ref. One of these underrated animals should be Australia’s 2032 Olympic mascot. Which would you choose? – https://theconversation.com/one-of-these-underrated-animals-should-be-australias-2032-olympic-mascot-which-would-you-choose-180794