Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Piers Kelly, Linguistic anthropologist, University of New England

Raychan on Unsplash

At this very moment, the words you are reading are entering your mind at the speed of thought. Below your awareness, strings of letters are retrieving words and meanings as effortlessly as oxygen absorbed into the bloodstream.

This efficiency is the result of careful refinements over time. The simple letters of the Roman alphabet are the successors to much more elaborate scripts like Egyptian hieroglyphics. As picture-based signs passed through new generations of users and into new languages, they apparently became more abstract, more compact, and fewer in number.

How then, do we make sense of the extraordinary Chinese writing system with its thousands of complex characters?

Read more:

If you speak Mandarin, your brain is different

Simplifying symbols

Over time, letters adapt to become simpler to write and easier to read. Cultural transmission theorists refer to this process as “compression” and it seems to kick in as soon as people start using a script and teaching it to others.

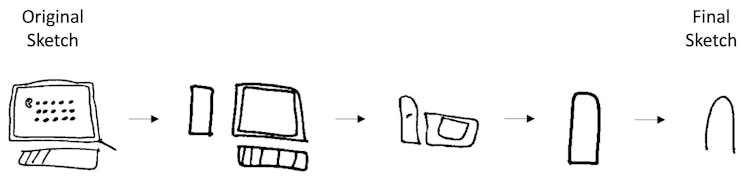

A delightful Pictionary-based experiment shows just how this might unfold in practice. A player who is asked to draw a computer monitor will sketch a detailed picture so the guesser has the best chance of success. But when those same two players are given the exact same clue again and again, the “monitor” might be reduced to a few rectangles and then a simple wavy line. As soon as a simpler convention is established it makes sense to cut corners.

But while English readers are only contending with 26 letters, readers of Chinese manage to process over 4,000 core characters, some made up of dozens of strokes.

The sign 麤 (cū, “to be rough with someone”), for example, is evidently much more complex than the alphabetic letter “o”. If Chinese writing is subject to similar pressures, why didn’t this sign simplify?

Our newly published research grapples with this very problem. We found the Chinese script has evolved towards greater visual complexity over the course of its 3,600 year history.

The traditional view

As early as the 1600s, European scholars began to compare archaeological inscriptions across different sites and historical periods.

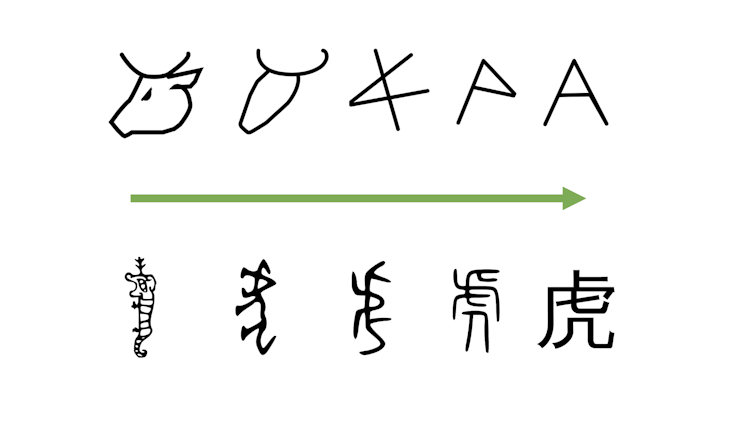

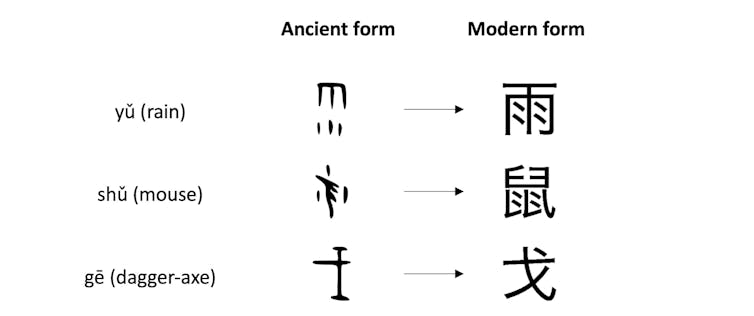

They noticed signs that started out as pictures tended to become simpler and more abstract over time.

Some of these scholars assumed the Chinese writing system had been trudging along a similar evolutionary path. Just as a hieroglyphic representation of a fish 𓆟 may have simplified into the letter D, and an ox’s head 𓃾 simplified into the letter A, Chinese characters are thought to have condensed from pictures of things to simpler sets of strokes.

Piers Kelly

Chinese philosophers of the Han Dynasty hypothesised their writing system originated at the hands of Fuxi (伏羲), China’s mythical first emperor, who invented characters inspired by the forms of birds, animals and elemental forces.

Later rulers were said to have simplified Fuxi’s pictures. Instead of representing the full outlines of the creatures, they began to trace only their tracks and movements. Tradition holds that a Qin dynasty emperor ordered his minister to simplify the script even further by reducing the total number of strokes in each character.

For over 350 years, scholars across the world have reproduced charts of Chinese characters that depict a straightforward sequence from stylised pictures towards abstract signs.

Even contemporary sources make the claim that Chinese has been steadily simplifying across its history. But our research suggests the opposite is true: Chinese writing has become increasingly complex.

How Chinese writing is different

The earliest surviving traces of Chinese writing are found scratched on turtle shells and ox bones used in divination rituals during the Shang Dynasty (c.1600 BC–c.1045 BC).

Since that time, the script has continued to evolve through several distinct historical phases that can be dated with accuracy.

We wanted to know how intricate Chinese character writing was over time. We used a computational method to trace the perimeters of each letter. The longer the perimeter, the more complex the drawing.

We used this method to measure more than 750,000 images of Chinese characters across five historical phases, from 1600 BC to the present day. The historical trajectories of many of these characters can be visualised here. Far from simplifying or staying the same, on average Chinese characters have become more complex with time.

Even when the mainland Chinese government engineered and enforced a simpler version of the script in 1956 this still left complexity above the level observed for 1600 BC.

Possible explanations

There is a kind of trade-off between the need for simplicity and the need to distinguish between each sign.

Unlike most other writing systems, the number of Chinese characters has increased dramatically over the millennia.

While alphabets pair letters with a limited set of individual sounds that recur and recombine, Chinese characters represent individual words or word-components together with information about sound values. This means that new characters can be created and added to an ever-expanding set.

As the set of Chinese characters became larger and larger over the centuries, writers found it necessary to add extra bells and whistles to increase the contrast and tell each character apart. A reader of Chinese text can absorb the words with ease because of innumerable tweaks that keep the system at just the right level of complexity.

The results shed new light on the history of the Chinese script. But they also provide important insights into the dynamics of human communication.

In order to work most efficiently, our symbolic systems require a careful balance between simplicity and distinctiveness.

Read more:

Un-doing the tián (field): Mandarin language and the shift away from Chinese agrarian culture

![]()

This research was conducted with Simon Jerome Han as lead author. Piers Kelly receives funding from an ARC DECRA Fellowship.

Charles Kemp’s work on this project was supported by an ARC Future Fellowship ( FT190100200).

James Winters does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Most assume writing systems get simpler. But 3,600 years of Chinese writing show it’s getting increasingly complex – https://theconversation.com/most-assume-writing-systems-get-simpler-but-3-600-years-of-chinese-writing-show-its-getting-increasingly-complex-194732