Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Joey Moloney, Senior Associate, Grattan Institute

Shutterstock

The Reserve Bank has lifted the cash rate for the second time in two months, this time by 0.50 points to 0.85%.

It won’t be the last such hike. Forecasters expect the cash rate to hit 2.5% by the end of next year. This would lift the typical variable mortgage rate to near 5%.

Cue the claims that the new generation of borrowers are entitled – they don’t know how good they’ve had it with such low rates.

But the refrain misses the full story. High house prices have changed the game, making it much harder for today’s borrowers.

It is true that even a mortgage rate of 5% is well below the peak of about 17% earlier generations paid at the start of the 1990s.

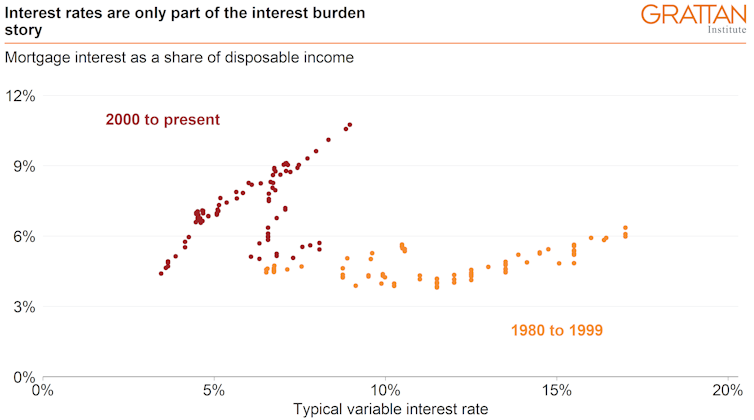

But the impact of those high rates on overall mortgage interest payments as a share of income was modest, because house prices were much lower then, and mortgages were much smaller.

RBA Tables E2 and F6; ABS National Accounts; Grattan analysis.

Typical house prices used to be about four times incomes. Now they’re more than eight times incomes, and more in Melbourne and Sydney.

This has meant that for any given mortgage rate, the share of income taken up by mortgage payments is much, much higher.

Source: RBA Tables E2 and F6

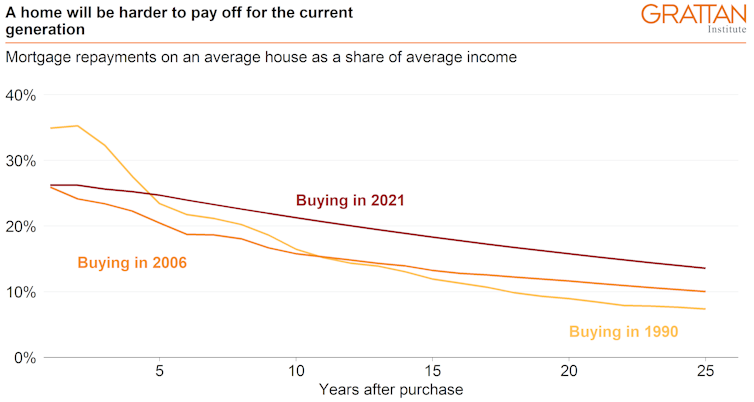

If you have a small loan with a high rate, all you need is a cut in rates, some inflation and decent income growth, and your mortgage burden can fall sharply.

That’s how it was for borrowers in the 1990s. High rates stung, but not for long.

Borrowers in the 1990s who started out devoting more than 30% of their income to paying off a mortgage found themselves devoting just 12% by the time the loan was halfway through.

Income is gross disposable income from ABS National Accounts. Historical interest rates are rolling 3-year averages of standard variable rates (discounted from 2004).

Projected interest rates are an average of past 10 years. Projected income growth is 3%.

Sources: ABS National Accounts and Residential House Prices; RBA Table F6; Yates (2011); Grattan Analysis

It’s different for someone who has borrowed recently.

If you have a big loan with today’s ultra-low interest rates, there’s only one way mortgage payments can go – and that’s up.

5% would hurt like it didn’t used to

Even if mortgage rates stabilise at around 5% – which is implied by some of the things the Reserve Bank governor has said – and wages grow faster than they have for a decade, the mortgage burdens of millennials who’ve bought houses recently won’t much decline.

The extraordinary increase in house prices and debt means mortgage rates of 7% would be as painful to borrowers today than rates of 17% were decades ago.

It’s a common barb that newer generations are struggling with home ownership and housing costs because of profligate spending, on smashed avos and the like.

Read more:

Paying off a home loan used to be easier than it looked. It’s now harder

But millennials spend less of their incomes on “discretionary” items – such as alcohol, clothes and household services – than people of the same age did decades ago.

What millennials are spending much more on is housing, simply because houses are so much more expensive.

So as the Reserve Bank continues to increase rates, it’s important to keep in mind that comparisons between then and now miss the full story.

Skyrocketing house prices have changed the game. For millennials, even historically small increases in interest rates will hurt.

![]()

Grattan Institute began with contributions to its endowment of $15 million from each of the Federal and Victorian Governments, $4 million from BHP Billiton, and $1 million from NAB. In order to safeguard its independence, Grattan Institute’s board controls this endowment. The funds are invested and contribute to funding Grattan Institute’s activities. Grattan Institute also receives funding from corporates, foundations, and individuals to support its general activities, as disclosed on its website.

Joey Moloney does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. The housing game has changed – why interest rate hikes hurt more than before – https://theconversation.com/the-housing-game-has-changed-why-interest-rate-hikes-hurt-more-than-before-184553