Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Scott Hollier, Adjunct Senior Lecturer – Science and Mathematics, Edith Cowan University

Shutterstock

When people hear the term “accessibility” in the context of disability, most will see images of ramps, automatic doors, elevators, or tactile paving (textured ground which helps vision impaired people navigate public spaces). These are physical examples of inclusive practice that most people understand.

You may even use these features yourself, for convenience, as you go about your day. However, such efforts to create an inclusive physical world aren’t being translated into designing the digital world.

Shutterstock

Accessibility fails

Digital accessibility refers to the way people with a lived experience of disability interact with the cyber world.

One example comes from an author of this article, Scott, who is legally blind. Scott is unable to purchase football tickets online because the ticketing website uses an image-based “CAPTCHA” test. It’s a seemingly simple task, but fraught with challenges when considering accessibility issues.

Despite Scott having an IT-related PhD, and two decades of digital accessibility experience in academic and commercial arenas, it falls on his teenage son to complete the online ticket purchase.

Screen readers, high-contrast colour schemes and text magnifiers are all assistive technology tools that enable legally blind users to interact with websites. Unfortunately, they are useless if a website has not been designed with an inclusive approach.

The other author of this article, Justin, uses a wheelchair for mobility and can’t even purchase wheelchair seating tickets over the web. He has to phone a special access number to do so.

Both of these are examples of digital accessibility fails. And they’re more common than most people realise.

We can clearly do better

The term “disability” covers a spectrum of physical and cognitive conditions. It can can range from short-term conditions to lifelong ones.

“Digital accessibility” applies to a broad range of users with varying abilities.

At last count, nearly one in five Australians (17.7%) lived with some form of disability. This figure increases significantly when you consider the physical and cognitive impacts of ageing.

At the same time, Australians are becoming increasingly reliant on digital services. According to a 2022 survey by consulting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers, 45% of respondents in New South Wales and Victoria increased their use of digital channels during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In contrast, research undertaken by Infosys in December 2021 found only 3% of leading companies in Australia and New Zealand had effective digital accessibility processes.

But have we improved?

Areas that have shown accessibility improvement include social media platforms such as YouTube, Facebook and Instagram, food ordering services such as Uber Eats, and media platforms such as the ABC News app.

Challenges still persist in online banking, travel booking sites, shopping sites and educational websites and content.

Data from the United States indicates lawsuits relating to accessibility are on the rise, with outcomes including financial penalties and requirements for business owners to remedy the accessibility of their website/s.

In Australia, however, it’s often hard to obtain exact figures for the scale of accessibility complaints lodged with site owners. This 1997 article from the Australian Human Right Commission suggests the conversation hasn’t shifted much in 25 years.

Shutterstock

There are solutions at hand

There’s a clear solution to the digital divide. The World Wide Web Consortium’s Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) standard has been widely adopted across the globe. It’s universally available, and is a requirement for all Australian public-facing government websites.

It guides website and app developers on how to use web languages (such as HTML and CSS) in ways that enable end users who rely on assistive technologies. There are no specialist technologies or techniques required to make websites or apps accessible. All that’s needed is an adherence to good practice.

Unfortunately, WCAG is rarely treated as an enforceable standard. All too often, adherence to WCAG requirements in Australia is reduced to a box-ticking exercise.

Our academic work and experience liaising with a range of vendors has revealed that even where specific accessibility requirements are stated, many vendors will tick “yes” regardless of their knowledge of accessibility principles, or their ability to deliver against the standards.

In cases where vendors do genuinely work towards WCAG compliance, they often rely on automated testing (via online tools), rather than human testing. As a result, genuine accessibility and usability issues can go unreported. While the coding of each element of a website might be WCAG compliant, the sum of all the parts may not be.

In 2016, the Australian government adopted standard EN 301549 (a direct implementation of an existing European standard). It’s aimed at preventing inaccessible products (hardware, software, websites and services) entering the government’s digital ecosystem. Yet the new standard seems to have achieved little. Few, if any, references to it appear in academic literature or the public web.

It seems to have met a similar fate to the government’s National Transition Strategy for digital accessibility, which quietly disappeared in 2015.

The carrot, not the stick

Accessibility advocates take different approaches to advancing the accessibility agenda with reticent organisations. Some instil the fear of legal action, often citing the Maguire v SOCOG case, where the 2000 Olympic website was found to be inaccessible.

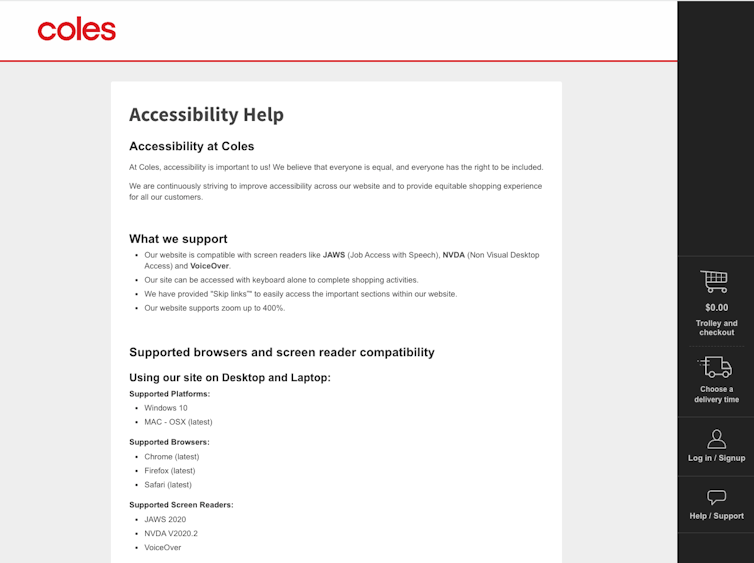

In a more recent example, the Manage v Coles settlement saw Coles agree to make improvements to their website’s accessibility after being sued by a legally blind woman.

Screenshot/Coles

In the Coles case, the stick became the carrot; Coles went on to win a national website accessibility award after the original complainant nominated them following their remediation efforts.

But while the financial impact of being sued might spur an organisation into action, it’s more likely to commit to genuine effort if this will generate a positive return on investment.

Accessible by default

We can attest to the common misconception that disability implies a need for help and support. Most people living with disability are seeking to live independently and with self-determination.

To break the cycle of financial and social dependence frequently associated with the equity space, governments, corporations and educational institutions need to become accessible by default.

The technologies and policies are all in place, ready to go. What is needed is leadership from government and non-government sectors to define digital accessibility as a right, and not a privilege.

Read more:

Making our cities more accessible for people with disability is easier than we think

![]()

Scott Hollier is on the board of the not-for-profit Disability in the Arts Disadvantage in the Arts (DADAA), and is CEO and Co-founder of the Centre For Accessibility Australia. The Centre for Accessibility Australia receives government grants for accessibility activity, but the funding has no specific bearing on the content of this article. The accessibility award that Coles won (after the Coles v Manage case) was awarded through the Centre for Accessibility Australia – however Scott was not involved in the voting for the award, or the nomination of Coles, and CFA was not involved in the website remediation.

This story is part of The Conversation’s Breaking the Cycle series, which is about escaping cycles of disadvantage. It is supported by a philanthropic grant from the Paul Ramsay Foundation.

Justin Brown is on the board of the not-for-profit Disability in the Arts Disadvantage in the Arts (DADAA)

– ref. Digital inequality: why can I enter your building – but your website shows me the door? – https://theconversation.com/digital-inequality-why-can-i-enter-your-building-but-your-website-shows-me-the-door-182432