Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By David Rowe, Emeritus Professor of Cultural Research, Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University

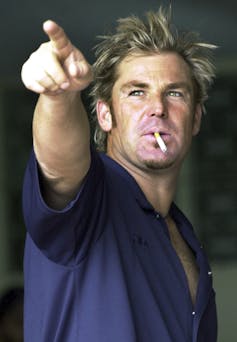

When the news broke it was tempting to conclude swiftly that Shane Warne died as he had lived. On holiday in Thailand, nudge nudge. The tabloids, especially in Britain where he lived much of his life, had luridly chronicled his life. Many may have speculated that he died living life to the fullest.

As it turned out, Warne, who was just 52, had declared he was on a serious health kick, trying to lose weight and get in condition. Previously, he had even managed to turn weight loss into a scandal, when he failed a drugs test at the 2003 Cricket World Cup in South Africa and was sent home. He was ridiculed for blaming his mother for recommending the banned diuretic.

To say Warne was no stranger to controversy is as banal as observing that he was a superlative cricketer. One of five Wisden Cricketers of the [20th] Century, cricket fans pore over his bowling record with the same forensic eye as the paparazzi tracked his carousing. It was Warne who delivered the “ball of the century” in 1993, perhaps the most famous dismissal in modern cricket, to a perplexed English captain, Mike Gatting. It was a piece of sporting sorcery that will never be forgotten.

These contrasting images lead us to ask who is Shane Warne, and why does he matter so much to so many?

Warnie: the soap opera

There are few sportspeople interesting enough to have an entire musical devoted to them, but Eddie Perfect found plenty of material for his 2008 production Shane Warne: The Musical. Its subject may be much admired by cricket followers around the world, but he is also well known to a much wider audience precisely because he has generated so much tabloid fare.

AAP/AP/M. Lakshman

Warne is often presented as the lovable larrikin, a masculine archetype long celebrated in Australia. This is a colonial-era image of young men who mocked the stuffy propriety of the British with cheeky, anti-authoritarian attitudes and behaviour.

Perfectly suited to play a key role in the “postcolonial pantomime” that is the Ashes cricket series, he was loud, untidy, disrespectful and, crucially, very good at beating the Poms at their own game.

Warne was radically different from other Australian cricket heroes like Sir Don Bradman and Richie Benaud. When the latter died in 2015, I reflected on his transition from on-field rebel to sober commentator.

Shane Warne also made the move to television commentary, but whereas Benaud offered dignified consideration, Warne was animated and opinionated. Restraint was never part of Warne’s armoury, although his successful career as a professional poker player and the subtlety of his bowling were evidence of a shrewd, calculating mind behind the brash exterior.

AAP/Joel Carrett

But Warne was a different type of larrikin from older cricketers like Dennis Lillee and Rod Marsh, who died on the same day in a different time zone.

Lillee and Marsh were creatures of the cricket world, aggressive practitioners of the art of demolishing opposition teams.

Read more:

Cricket, commentary and the dollar: Benaud’s legacy is complex

Warne moved well beyond this sphere, as the emergent global sport star system fully embraced gossip-based entertainment.

He was both product and producer of the sporting celebrity that now moves effortlessly across the cultural landscape. He unblushingly endorsed hair loss treatment. Warne’s doomed engagement to British film star Liz Hurley was a classic case of a relationship conducted largely in the media spotlight.

The arrival of social media, and the pocket cameras always on hand to upload “evidence” of a transgression, was crucial in shaping the world’s knowledge of Warne the man when he was not performing astonishing feats on the cricket field.

He is, therefore, much closer to the postmodern cohort embodied by “bad as I wannabe” US basketballer Dennis Rodman than traditional Australian sporting larrikins.

More than just a cricketer

There is no need to persuade cricket fans to remember Shane Warne. His phenomenal record places him firmly in the cricket pantheon. But he is also important to sport in general and beyond the world of bat and ball.

Warne reminds us that sport is always much more than performance on the field. It is not just a question of what is done, but how. There is as much fascination with the back story as the big game.

An indifferent student from suburban Melbourne, Warne was socially mobile purely because of his sporting prowess. This everyman did extraordinary things with bravado, but was also a flawed personality. From his ill-advised early fraternisation with bookmakers to his feuding with past and current players, Warne became Warnie, almost a caricature of the sporty Aussie bloke loved by some and disdained by others.

Warne compulsively sought and attracted attention. Despite his expression of sadness about his family relationships in the documentary Shane, he insisted “I smoked, I drank, I bowled a bit. No regrets”.

Onlookers alternatively admire and criticise this life led on its own terms. It is in the conversational space between that Warne lives on.

![]()

David Rowe has received funding from the Australian Research Council for the Discovery Projects ‘A Nation of “Good Sports”? Cultural Citizenship and Sport in Contemporary Australia’ (DP130104502) and ‘Australian Cultural Fields: National and Transnational Dynamics’ (DP140101970).

– ref. Vale Shane Warne: a cricketing genius who lived a life of ‘no regrets’ – https://theconversation.com/vale-shane-warne-a-cricketing-genius-who-lived-a-life-of-no-regrets-178603