Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Darren Koppel, Research fellow, Curtin University

Environmental scientists see flora, fauna and phenomena the rest of us rarely do. In this series, we’ve invited them to share their unique photos from the field.

This week the federal government announced A$804.4 million over ten years to bolster Australia’s scientific and strategic presence in Antarctica. Of this, $14.3 million is for cleaning up legacy waste from the continent – the abandoned waste and contamination accumulated from over a century of human visitors.

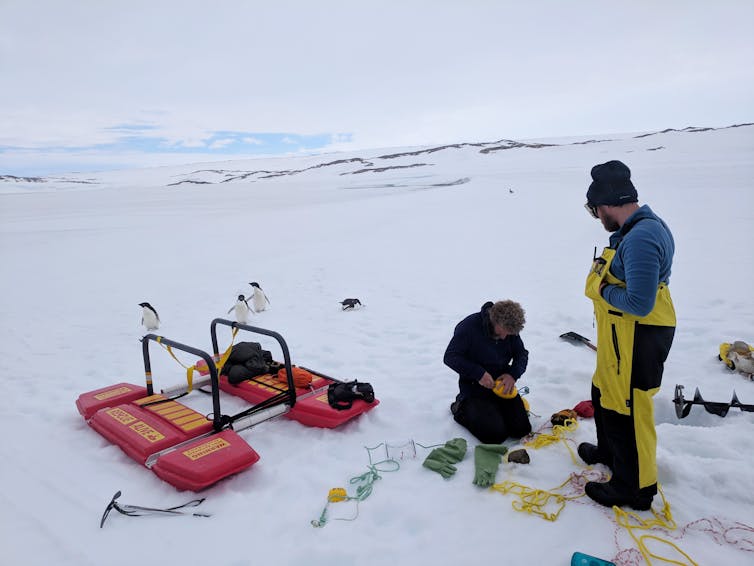

That there’s legacy waste in Antarctica may come as a surprise to some people, as we often think of Antarctica as a pristine wilderness. However, I’ve seen legacy waste first hand when I was in Antarctica over the 2017-2018 summer, researching how this waste impacts local environments.

One study site, for example, was Australia’s Wilkes station, a research station abandoned in 1969 after being buried in snow and ice. A 2013 study estimated its tip site contains 20,000 cubic metres of waste, including leaking oil drums, batteries, dead dogs, building material, and food.

Australia’s responsibility for its historical waste in Antarctica is both a moral and legal imperative. This funding announcement will hopefully be the start of a renewed push to clean up this once pristine frontier.

Darren Koppel

Waste and the Madrid Protocol

Humans have occupied Antarctica since the early 1900s. But the big push into Antarctica occurred during the International Geophysical Year in 1957-1958, which saw 12 nations build 60 stations. Today, there are 158 locations with over 5,342 buildings, including currently operating and abandoned research stations and field camps.

Australia and other nations signed the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty System, or “the Madrid Protocol”, which came into force in 1998. The Madrid Protocol designates Antarctica a “natural reserve, devoted to peace and science” and requires its comprehensive protection. Australia played a leading role in its development, including by ensuring mining was banned in Antarctica.

Thanks to the Madrid Protocol, human activities in Antarctica today generally pose a low-risk to the environment.

Darren Koppel

Pollution in Antarctica can come from a number of sources. Contaminants including metals, microplastics, and persistent organic pollutants can hitch a ride on wind and ocean currents. However, these are so low in concentration they’re unlikely to cause harm.

Tourism and active research stations also generate contamination from wastewater, diesel exhaust and incineration smoke, and localised fuel spills. These sources are generally well managed and new technologies are being implemented to minimise these impacts.

Prior to the Madrid Protocol, waste from stations was pushed into the ocean, buried or incinerated on land, or placed in tip sites – many of which remain today. Abandoned research stations and field camps, old oil spills, and historical tip sites still dot the continent and are generally unmanaged.

Darren Koppel

Darren Koppel

Competing with nature for ice-free land

A key issue is where this legacy waste is located. Over three-quarters of stations are built on the ice-free Antarctic coastline, which makes up just 0.06% of the continent. This is a practical decision because coastal locations are more accessible by boats, and moving ice sheets have a tendency to become icebergs).

But while building on the ice-free coast is good for us, it can cause problems for local wildlife. Ice-free areas are rare real-estate in Antarctica and much of the land-based biodiversity depends on it.

Marine birds and mammals nest among the rocks, lichens and mosses live in and around the streams of melted ice, which are also home to microinvertebrate communities (think tardigrades) and different types of microalgae. Concentrating our human activity to these areas concentrates our impact to Antarctica’s most sensitive ecosystems.

Darren Koppel

Australia, in many ways, is leading the Antarctic national programs developing clean-up technologies and science. For example, developing new technologies to remediate soils contaminated by fuel spills and undertaking studies to map the types of contaminants associated with legacy waste.

A lingering concern is that contaminants can leach from waste into surrounding environments, particularly in summer when melted ice streams flow through these sites.

My research, published last year, sampled these streams and along the coastlines to measure the concentrations of metals. Copper and zinc, which are toxic at high concentrations, were higher in some streams, and this correlated with a decreased number of algae species.

Darren Koppel

Darren Koppel

What’s needed to clean up Antarctica

Despite the protocol being in force since 1998, there’s been a clear lack of action to clean up this waste from many nations. It begs the question: just how committed are we to monitoring human impacts in Antarctica?

My biggest concern is that the lack of any legal enforcement, lack of monitoring, and an uncertainty in how exactly to clean up can be used as an excuse to delay, or even avoid, any effort.

But while cleaning up our legacy waste is a huge undertaking, there have been successful examples, such as the remediation of Australia’s Old Casey Station tip-site in 2003 and 2004.

Darren Koppel

Likewise, the US’ McMurdo Station operated a nuclear reactor for power between 1961 and 1972, called “Nukey Poo”. The whole site required substantial remediation after it closed in 1972. This involved the removal of 12,000 tonnes of rock and soil over seven years for disposal in the USA to ensure no radioactive contamination was left in Antarctica.

These clean ups, however, are the exceptions rather than the norm, and there’s a lot left to do. The tip site at Australia’s abandoned Wilkes Station, for example, is ten times the size of the Thala Valley tip, which took more than ten years to clean up. And Australia’s other active Antarctic research stations, Mawson and Davis, have historical tip sites that are less studied.

Darren Koppel

The $14.3 million promised by the federal government to clean this mess will also go towards a new geospatial information system. This will hopefully see proper documentation of all waste sites.

Other necessary steps to clean up Antarctica include the characterisation of the types and quantities of waste, the development of environmental quality standards, and new clean up technologies.

But it will take more than platitudes, and it must be followed by a dedicated effort to actually remove the waste, in line with the Madrid Protocol signed 30 years ago. The funding is a good step towards meeting our obligations, but we need to be in it for the long haul.

Read more:

For the first time, we can measure the human footprint on Antarctica

![]()

Darren Koppel worked on an Australian Antarctic Science funded project (AAS4326), received funding from an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, and received a bursary from Antarctic Science Ltd to conduct research on contaminants in Antarctica. He is not affiliated with the Australian Antarctic Division. Darren is currently employed by Curtin University and is working on a project funded by National Energy Resources Australia to investigate the ecological risk of contaminants from decommissioning activities.

– ref. Dead dogs, leaking oil drums, batteries: Antarctica’s abandoned waste gets funding boost to kickstart the clean up – https://theconversation.com/dead-dogs-leaking-oil-drums-batteries-antarcticas-abandoned-waste-gets-funding-boost-to-kickstart-the-clean-up-177711