Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Graeme Gillespie, Honorary Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne

Australia is home to more than 240 frog species, most of which occur nowhere else. Unfortunately, some frogs are beyond help, with four Australian species officially listed as extinct.

This includes two remarkable species of gastric-brooding frog. To reproduce, gastric-brooding frogs swallowed their fertilised eggs, and later regurgitated tiny baby frogs. Their reproduction was unique in the animal kingdom, and now they are gone.

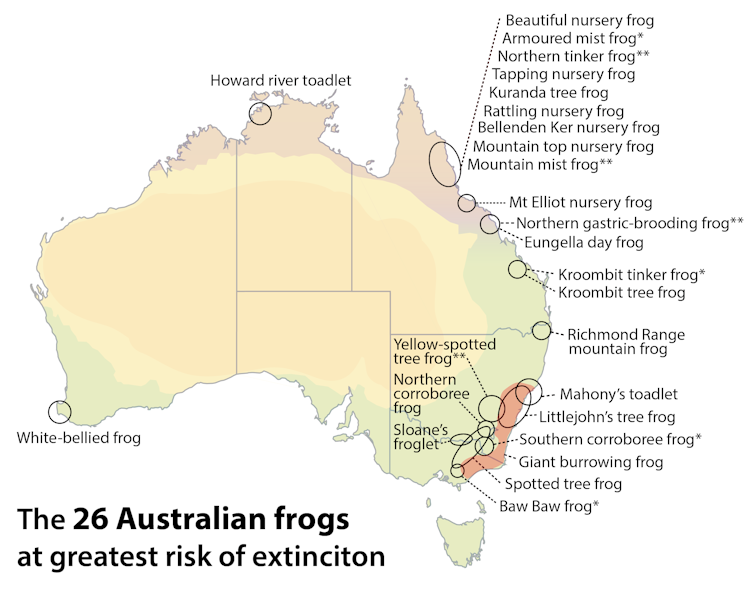

Our new study published today, identified the 26 Australian frogs at greatest risk, the likelihood of their extinctions by 2040 and the steps needed to save them.

Tragically, we have identified an additional three frog species that are very likely to be extinct. Another four species on our list are still surviving, but not likely to make it to 2040 without help.

Hal Cogger

The 26 most imperilled frogs

The striking yellow-spotted tree frog (in southeast Australia), the northern tinker frog and the mountain mist frog (both in Far North Queensland) are not yet officially listed as extinct – but are very likely to be so. We estimated there is a greater than 90% chance they are already extinct.

Jaana Dielenberg/Threatened Species Recovery Hub

The next four most imperilled species are hanging on in the wild by their little frog fingers: the southern corroboree frog and Baw Baw frog in the Australian Alps, and the Kroombit tinker frog and armoured mist frog in Queensland’s rainforests.

The southern corroboree frog, for example, was formerly found throughout Kosciuszko National Park in the Snowy Mountains. But today, there’s only one small wild population known to exist, due largely to an introduced disease.

Without action it is more likely than not (66% chance) the southern corroboree frog will become extinct by 2040.

David Hunter/DPIE NSW

David Hunter/DPIE NSW

What are we up against?

Species are suffering from a range of threats. But for our most recent extinctions and those now at greatest risk, the biggest cause of declines is the amphibian chytrid fungus disease.

This introduced fungus is thought to have arrived in Australia in the 1970s and has taken a heavy toll on susceptible species ever since. Cool wet environments, such as rainforest-topped mountains in Queensland where frog diversity is particularly high, favour the pathogen.

The fungus feeds on the keratin in frogs’ skin — a major organ that plays a vital role in regulating moisture, exchanging respiratory gases, immunity, and producing sunscreen-like substances and chemicals to deter predators.

Robert Puschendorf

Conrad Hoskin

Another major emerging threat is climate change, which heats and dries out moist habitats. It’s affecting 19 of the imperilled species we identified, such as the white-bellied frog in Western Australia, which develops tadpoles in little depressions in waterlogged soil.

Climate change is also increasing the frequency, extent and intensity of fires, which have impacted half (13) of the identified species in recent years. The Black Summer fires ravaged swathes of habitat where fires should rarely occur, such as mossy alpine wetlands inhabited by the northern corroboree frog.

Invasive species impact ten frog species. For the spotted tree frog in southern Australia, introduced fish such as brown and rainbow trout are the main problem, as they’re aggressive predators of tadpoles. In northern Australia, feral pigs often wreak havoc on delicate habitats.

Conrad Hoskin

Emily Hoffmann

So what can we do about it?

We identified the key actions that can feasibly be implemented in time to save these species. This includes finding potential refuge sites from chytrid and from climate change, reducing bushfire risks and reducing impacts of introduced species.

But for many species, these actions alone aren’t enough. Given the perilous state of some species in the wild, captive conservation breeding programs are also needed. But they cannot be the end goal.

Peter Taylor/Threatened Species Recovery Hub

Captive breeding programs can not only establish insurance populations, they can also help a species persist in the wild by supplying frogs to establish populations at new suitable sites.

Boosting numbers in existing wild populations with captive bred frogs improves their chance of survival. Not only are there more frogs, but also greater genetic diversity. This means the frogs have a better chance of adapting to new conditions, including climate change and emerging diseases.

Our knowledge of how to breed frogs in captivity has improved dramatically in recent decades, but we need to invest in doing this for more frog species.

Finding and creating wild refuges

Another vital way to help threatened frogs persist in the wild is by protecting, creating and expanding natural refuge areas. Refuges are places where major threats are eliminated or reduced enough to allow a population to survive long term.

For the spotted-tree frog, work is underway to prevent the destruction of frog breeding habitat by deer, and to prevent tadpoles being eaten by introduced predatory fish species. These actions will also help many other frog species as well.

The chytrid fungus can’t be controlled, but fortunately it does not thrive in all environments. For example, in the warmer parts of species’ range, pathogen virulence may be lower and frog resilience may be higher.

Chytrid fungus completely wiped out the armoured mist frog from its cool, wet heartland in the uplands of the Daintree Rainforest. But, a small population was found surviving at a warmer, more open site where the chytrid fungus is less virulent. Conservation for this species now focuses on these warmer sites.

This strategy is now being used to identify potential refuges from chytrid for other frog species, such as the northern corroboree frog.

Michael Williams/Its A Wildlife Photography

No time to lose

We missed the window to save the gastric-brooding frogs, but we should heed their cautionary tale. We are on the cusp of losing many more unique species.

Decline can happen so rapidly that, for many species, there is no time to lose. Apart from the unknown ecological consequences of their extinctions, the intrinsic value of these frogs means their losses will diminish our natural legacy.

In raising awareness of these species we hope we will spark new action to save them. Unfortunately, despite persisting and evolving independently for millions of years, some species can now no longer survive without our help.

![]()

Graeme Gillespie is employed by the NT Government, and is the President of the Australian Society Herpetologists.

This research has been funded at various points by: Queensland Government Community Sustainability Action Grant, National Environmental Research Program (NERP) Grant, Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund

Hayley Geyle receives funding from the National Environmental Science Program through the Threatened Species Recovery Hub.

Jaana Dielenberg works for the Threatened Species Recovery Hub which receives funding from the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program.

Nicola Mitchell receives funding from the National Environmental Science Program through the Threatened Species Recovery Hub, and is a member of the Commonwealth Threatened Species Scientific Committee.

Stephen Garnett receives funding from the National Environment Science Program Threatened Species Recovery hub

– ref. We name the 26 Australian frogs at greatest risk of extinction by 2040 — and how to save them – https://theconversation.com/we-name-the-26-australian-frogs-at-greatest-risk-of-extinction-by-2040-and-how-to-save-them-166339