Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Alice Clement, Research Associate in the College of Science and Engineering, Flinders University

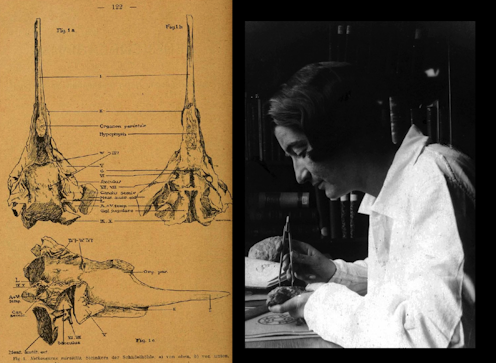

Biodiversity Heritage Library/ Harvard University Archives

Modern palaeontology dates back to the 19th century. But from time to time, entirely new branches of enquiry are developed.

This year marks 100 years since the birth of palaeoneurology, the study of “fossil brains”. Notably, it serves as an important reminder of the late Tilly Edinger, without whom the field could not have evolved as it has.

Wiki

As the name suggests, palaeoneurology combines the study of fossils with neural evolution. It allows us to understand how animal brains evolved through deep time to give rise to the remarkable diversity we see today.

When animals die, their soft parts — including the brain — decay quickly, leaving only the hard parts of the skeleton to potentially become fossilised. Understandably, this makes the study of these soft parts difficult for palaeontologists.

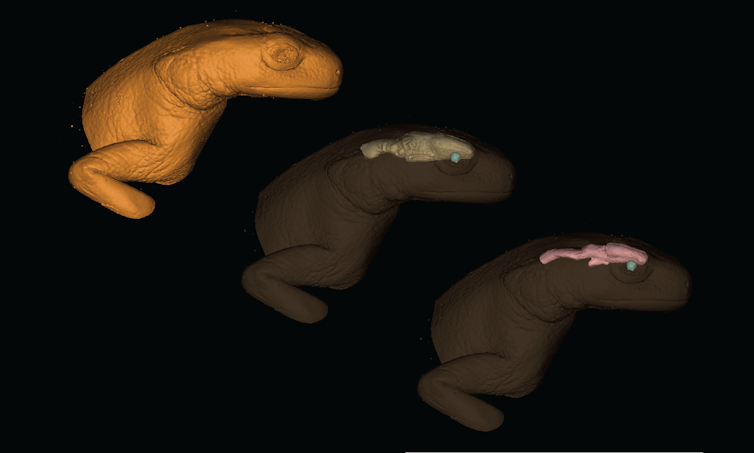

Researchers get around this by creating a mould of the internal space of the skull that would have housed the brain during an animal’s life. This is called an “endocast”.

The size and shape of an animal’s endocast can give insight into their ecology and behaviour. For example, sharks are known for their good sense of smell, whereas fish such as trout are more so considered visual predators.

It’s no surprise then that when we compare the brains of sharks and fish, we see differences in the relative size of the regions associated with smell and vision.

Author provided

By studying the endocasts of extinct animals, we can identify when major evolutionary innovations likely occurred. And this helps us pinpoint the origins of certain behaviours, such as flight, or the transition to land.

Tilly Edinger and 100 years of ‘fossil brains’

Tilly Edinger (1897–1967), a vertebrate palaeontologist from Frankfurt, Germany, founded palaeoneurology in 1921 by combining her unique training in geology and neurology.

She was the first person to apply a deep time perspective to brain evolution, and consider endocasts from throughout the geological record as more than mere curiosities.

But perhaps what is particularly remarkable is that Edinger pioneered this whole new field of research while living under an increasingly restrictive Nazi Germany, from where she was eventually forced into exile.

During her dissertation studies at Frankfurt University, her supervisor Professor Fritz Drevermann suggested she study the palate (roof bones of the mouth) of an extinct marine reptile called Nothosaurus.

While doing so, she noticed the specimen had preserved a natural endocast, as sediment had filled the skull. Edinger compared this with an endocast of the living alligator for her first paper. Her thesis which followed was published on this day 100 years ago.

FunkMonk (CC BY-SA 3.0)

‘The fossil vertebrates will save me’

Despite her social standing and gender (at a time when it was unusual for wealthy women to pursue further education or employment), Edinger became an established and respected scientist.

However, during her time working at the Senckenberg Museum of Natural History in the 1930s, the rise and influence of the Nazi regime gradually restricted her freedoms and eventually forced her to flee.

It was due to her impressive reputation, as well as supporting letters from several influential scientists such as Alfred S. Romer, that Edinger eventually managed to escape in 1939.

Indeed, before she fled she seemingly acknowledged that her research contributions and standing in the scientific community would ultimately play a role in her survival.

In a letter to a colleague she wrote, “warden mich also die fossilen Wirbeltiere retten” — which translates to “one way or another, the fossil vertebrates will save me”.

flickr

After a period of temporary refuge in London, in 1940 Edinger took up a position at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology in the United States, where she worked until her death.

She was highly respected around the world — receiving three honorary doctorates. She was also the first woman to be elected president of the largest and most prestigious palaeontological association, the Society of Vertebrate Palaeontology.

Read more:

When our evolutionary ancestors first crawled onto land, their brains only half-filled their skulls

Edinger’s work extended to amphibians, horses, pterosaurs and whales among others. Her magnum opus — an annotated bibliography titled Paleoneurology 1804-1966 — remains a prominent resource for scientists working in palaeoneurology today.

Creative Commons

Advancing deafness contributed to Edinger’s untimely death. In 1967, aged 69, she was struck by a truck on her way to work and eventually succumbed to her injuries.

Palaeoneurology today

Traditionally, scientists had to rely on rare natural moulds of endocasts, or destroy specimens via serial grinding to study the internal space of a skull. Advances in imaging technology has transformed this field in its most recent revival.

These days, palaeoneurologists routinely use CT-scanning to create digital endocasts without damaging specimens. These advances are enabling increasingly detailed analyses, and a whole new generation of “brainy” scientists are carrying on Edinger’s brilliant and pioneering legacy.

![]()

Dr Alice Clement receives funding from The Australian Research Council.

– ref. Remembering Tilly Edinger, the pioneering ‘brainy’ woman who fled Nazi Germany and founded palaeoneurology – https://theconversation.com/remembering-tilly-edinger-the-pioneering-brainy-woman-who-fled-nazi-germany-and-founded-palaeoneurology-160194