Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Jonathan Symons, Director of Research and Innovation, School of International Studies, Macquarie University

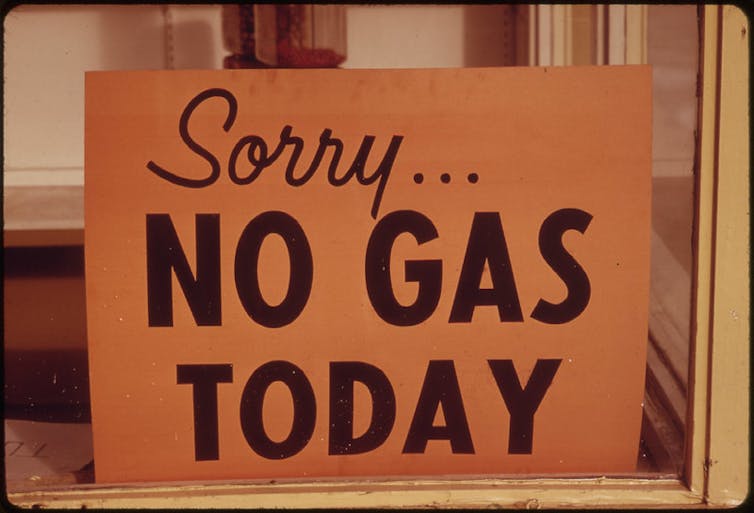

In the 1960s, major oil-producing nations formed a cartel to drive up the price of oil. It worked. For decades, nations in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) have agreed to manage supply and raise prices.

Economists have long recognised cartel market power can bring accidental environmental benefits. By driving up prices, demand for polluting products drops. One recent analysis found OPEC’s actions had avoided 67 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions between 1971 and 2021 – equivalent to around three years of global oil consumption.

There’s no OPEC for thermal coal. However, Australia and Indonesia together account for around two thirds of seaborne thermal coal exports. If these two nations began acting in tandem to end the approval of new mines, falling future supply would gradually increase prices.

Our recent research points out that a formal treaty to phase out new thermal coal mine approvals would not only bring climate benefits, but could also benefit national budgets, state royalties and regional jobs.

What we’re proposing blends climate action and self-interest. If restricting coal supply boosted prices, producer states would benefit from increased royalties. Owners and workers at existing mines would benefit from stabilising prices. Finally, the green energy transition would be protected from being undermined by a race to consume ultra-cheap coal.In the 1970s, OPEC’s engineering of higher oil prices drove a shift to more fuel-efficient cars and triggered intense interest in alternative energy sources such as solar. In our time, solar, wind and energy storage have come of age. A treaty to end new coal mines would make the shift even more appealing.

U.S National Archives

What would this look like?

If Australia, Indonesia and others formed a new “Organisation for Coal Transition”, the environmental motivation wouldn’t be the only difference with OPEC. For a start, a much high share of oil is traded internationally than coal, as more countries have their own coal supplies.

But major coal importers such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan now depend on seaborne coal. These nations are committed to accelerating climate action overall and have shown signs of structural demand decline already. Stronger coal prices would spur on the change.

The limited number of major coal exporters also creates potential for cooperation. In 2024, Indonesia controlled almost half of global exports, while Australia’s share was nearly 20%. Projections. If South Africa and Colombia joined a treaty alongside Australia and Indonesia, they would together account for 80% of seaborne exports.

What’s more, a thermal coal export treaty would not be easy to undermine. It takes years to get new mines producing, and deepwater ports able to take coal carriers are limited.

Coal importers could reinforce this treaty, pledging to buy from treaty members alone. Japan and South Korea (which account for 20% of global coal imports) are both seeking a predictable energy transition. These countries have shown willingness to pay a green premium and are investors in existing mines.

Australia has no exit strategy

Despite efforts to close domestic coal plants, Australian policymakers have done nothing to limit coal mining and exports.

New South Wales and Queensland state governments still benefit significantly through royalties and regional jobs. Australia’s coal exports, mine expansion approvals and new applications show little sign of slowing.

This is an increasingly risky strategy. With profit margins falling from recent highs and shifting demand in key markets, the thermal coal industry risks a chaotic future for mining towns.

While policymakers are beginning to focus on transition challenges for a small number of coal mines slated to close, they have largely avoided active intervention. After the NSW Productivity Commission and Net Zero Commission recommended limiting new coal mine approvals, Premier Chris Minns described the idea as “irresponsible”.

A ban backed by industry?

For operators of existing mines, agreeing to limit expansion opportunities is a challenging proposition. But the longer-term benefits would be much clearer if it was coordinated with international competitors and supported by buyers.

The coal export sector is showing signs of shifting to a buyers’ market, as long-term demand plateaus and then declines. This puts exporters such as Australia, Colombia, Indonesia and South Africa at a clear disadvantage.

We’ve already seen the fallout of coal’s market-driven decline in the United States’ Appalachian region Repeating the same mistake would undermine regional communities.

If, however, the shift was well managed, it would be a crucial step towards a coordinated just transition.

Japanese, Chinese, South Korean, Indian and Singaporean firms hold major stakes in Australian and Indonesian coal projects. These investors would benefit if existing assets are safeguarded from oversupply. These same investors would likely rally against more forceful interventions to close existing mines or raise mining taxes.

Climate action for pragmatists

Thermal coal is still mined in almost 60 countries. But only 11 have new mines seeking approval. At the same time, key international importers such as China, India, the European Union, Japan and South Korea are actively aiming to cut coal imports. A no-new-mines treaty would meet countries where they are.

What we are proposing is a pragmatic way to advance climate action. Rather than shuttering existing mines and risking blowback, the treaty and its cartel logic would align Australia’s economic self-interest and its climate goals.

At the United Nations climate talks last year, federal Minister for Climate and Energy Chris Bowen supported efforts to map a fossil fuel phase-out. To date, there’s no clarity on how Australia, a fossil fuel export giant, could do that.

Firmly closing the door to new mines alongside other exporters could offer a way to do this while giving policymakers agency.

The approach we’re proposing wouldn’t end coal use. But it would solve several problems at a stroke – and take a big step forward in the energy transition.

![]()

Jonathan Symons is an ordinary member of WePlanet NGO.

Chris Wright is the Principal Analyst at CarbonBridge, a small consulting group aiming to bridge critical decarbonisation challenges. He has been involved in work around the UN climate negotiations for over a decade.

– ref. If Australia and Indonesia agreed to end new thermal coal mines, it could drive the green transition. – https://theconversation.com/if-australia-and-indonesia-agreed-to-end-new-thermal-coal-mines-it-could-drive-the-green-transition-271309