Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Matt Absalom, Senior Lecturer in Italian Studies, The University of Melbourne

If you watch American cooking shows, you’ve likely experienced “salad confusion”. You see a chef preparing what looks like rocket, but they call it arugula.

It’s the same plant (Eruca sativa). It has the same peppery bite. So why do English speakers use two completely different names?

The answer isn’t just a quirk of translation. It is a linguistic fossil record revealing the history of Italian migration.

The name you use tells us less about the vegetable and more about who introduced you to it.

A Latin word with a double life

It all starts with the Latin word eruca.

Crucially, this term had a dual meaning. It referred to the vegetable, but also meant “caterpillar” – maybe because the plant’s hairy stems resembled the pests often found on brassicas.

As the Roman Empire faded and Vulgar Latin (the language of the vulgus, or the common people) evolved into the Romance languages, this single word split along two paths.

The Northern route: aristocratic ‘rocket’

As the word travelled north through Italy, it morphed from eruca into the Northern Italian diminutive ruchetta.

From there, it crossed the Alps into France, becoming roquette.

By the 16th century, French culinary influence was dominant in England. The first written record appears in 1530, in John Palsgrave’s text L’esclarcissement de la langue francoyse (Clarification of the French Language – said to be the first grammar of French for English speakers), translating roquette to “rocket”.

Missouri Botanical Garden, Peter H. Raven Library

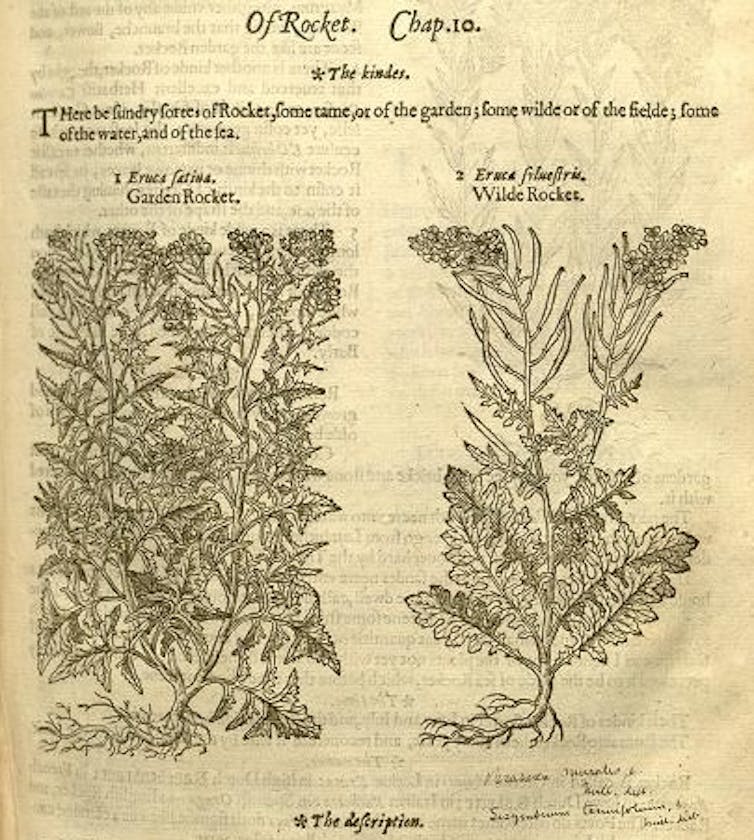

By 1597, English botanist John Gerard was describing “garden rocket” in his large illustrated Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes, cementing it in the British lexicon.

This terminology travelled with the First Fleet. In Australia, “rocket” was a colonial staple, not a modern discovery. Planting guides in the Hobart Town Courier from 1836 list rocket alongside other brassicas, such as cress and mustard, as essential kitchen garden crops.

This is why people in Australia, the United Kingdom and New Zealand say “rocket”. For these speakers, the word followed an aristocratic, pre-industrial path.

Trove

The Southern route: migrant ‘arugula’

In the United States, the word “arugula” didn’t arrive in books; it arrived in pockets.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, millions of Italians emigrated to the US. This was a mass migration of the working class, predominantly from Southern regions like Calabria and Sicily.

These migrants spoke regional languages, erroneously called dialects, rather than Standard Italian.

In the South, eruca had evolved differently. We can trace this in historical dictionaries: Gerhard Rohlfs’ monumental Dictionary of the Three Calabrias (1932–39) records the local word as arùculu.

Similarly, Antonino Traina’s Sicilian-Italian dictionary (1868) lists the variant aruca.

When Italian immigrants established market gardens in New York, they sold the produce using their dialect forms. They weren’t selling the French roquette; they were selling the Calabrian arùculu.

Detroit Publishing Co/Library of Congress

Over many years, this solidified into the American English “arugula”.

For decades, arugula was an “ethnic” ingredient in the US, underscoring its origins as “an unruly weed that was foraged from the fields by the poor”. It wasn’t until a New York Times article on May 24 1960 that food editor Craig Claiborne introduced it to a wider audience.

Noting it “has more names than Joseph’s coat had colors”, he used the New York market term “arugula” alongside rocket in his recipes, inadvertently codifying it as the standard American name.

There is perhaps a sense that “arugula” might come from Spanish, given the influence of words like cilantro in American culinary terminology.

In Spanish, Latin eruca evolved into oruga which is uncannily similar to “arugula”. But, linguistically things are a little more complex.

While the Spanish word maintains the reference to the plant it also retains the Latin term’s double meaning: a salad vegetable and a caterpillar.

According to Bréal’s Law of Differentiation, named for the linguist Michel Bréal, languages detest absolute synonyms. If a word has two meanings, the language will intervene somehow. Indeed, today’s Spanish speakers prefer to call the plant rúcula. If you were to ask for an ensalada de oruga in Spain today, you’d probably get odd looks and, maybe, a caterpillar salad.

What about ‘rucola’?

So where does the word rucola – seen on menus in Rome today – fit in?

While the Anglosphere was splitting into rocket and arugula, Italy was undergoing its own linguistic unification. Standard Italian rucola is another diminutive which gradually won out over other regional variants.

Philologically, rucola represents a middle ground. Its rise in usage in Italy in the second half of the 20th Century eclipsed competing terms like rughetta, ruchetta or ruca.

Rucola now has international reverberations. The preferred term in Spanish is modelled on it, it appears in many other European languages and it is making inroads in the English lexicon.

From peasant weed to political symbol

By the 1990s in the US, the “peasant weed” had completed a remarkable social climb. It became a political shibboleth for the American “liberal elite” (most famously during Obama’s Arugula-gate in the 2008 presidential election campaign).

Meanwhile, in Australia, rocket popped up as the ubiquitous garnish of the cafe culture boom found on everything from pizza to smashed avo.

The divide is a reminder that language is rarely accidental. When an Australian orders “rocket,” they echo a 16th-century exchange with France. When an American orders “arugula”, they echo the voices of Southern Italian migrants in 1920s New York. And when someone uses “rucola” perhaps it’s a way of evoking Italy’s mythical, UNESCO-awarded gastronomy.

![]()

Matt Absalom does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Rocket or arugula? How a salad vegetable mapped the Italian diaspora – https://theconversation.com/rocket-or-arugula-how-a-salad-vegetable-mapped-the-italian-diaspora-272059